Wakefield Press

Tasmanian Robert Cox is a former copywriter, journalist, newspaper subeditor, and magazine editor with a special interest in the history of his home state. His publications include seven other books and numerous articles, essays, short stories, and reviews, plus an unobtrusive poem or two. He has also done voice work in radio and television and written documentary film scripts.

Wakefield Press

16 Rose Street

Mile End

South Australia 5031

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2021

This edition published 2022

Copyright Robert Cox, 2021

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

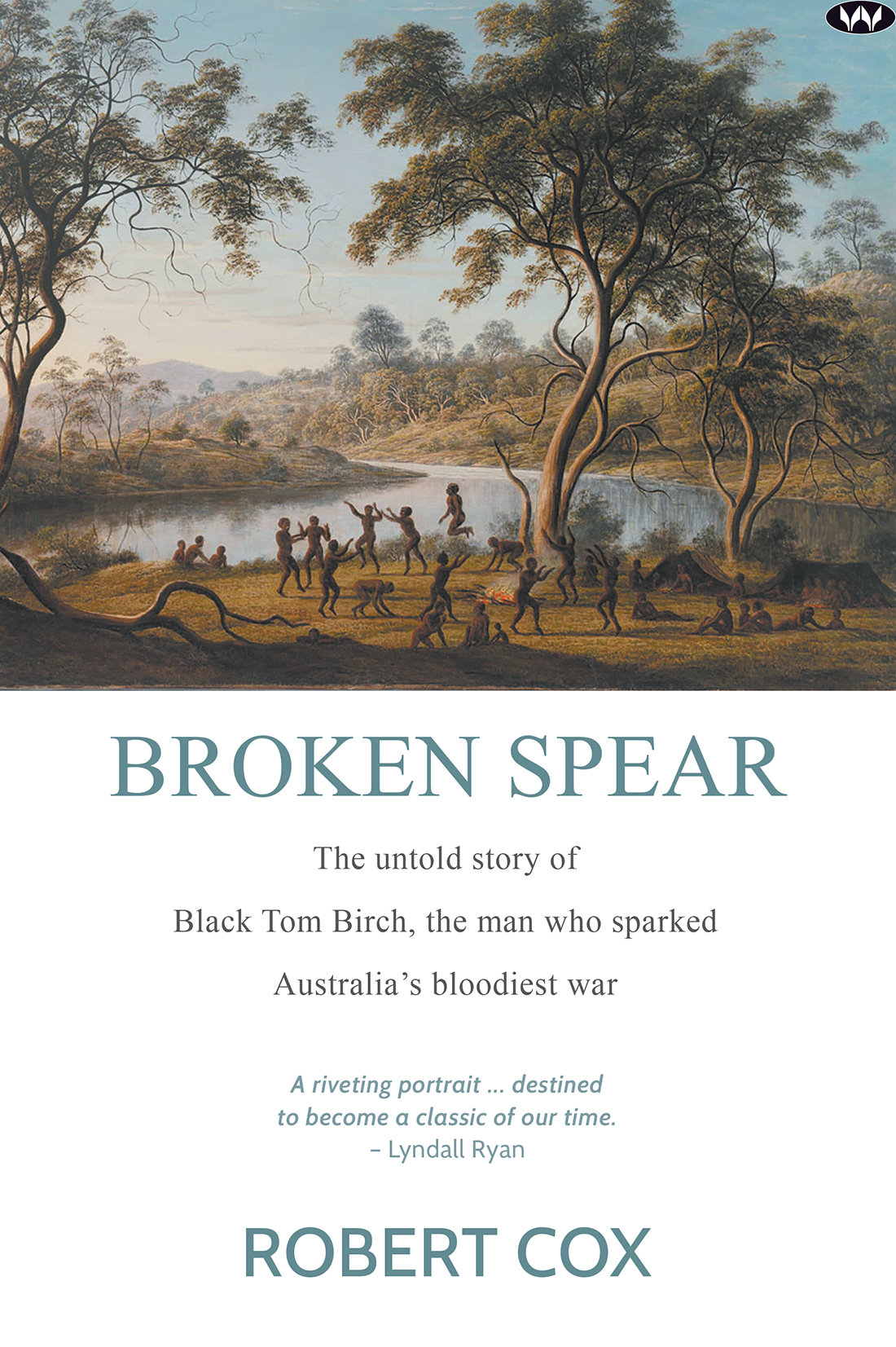

Cover designed by Stacey Zass

Edited by Julia Beaven, Wakefield Press

ISBN 978 1 74305 911 1

For Lou with love, admiration, and gratitude

In 1811 Governor Lachlan Macquarie, trekking through the Tasmanian Midlands from south to north during the first of his two visits to the island, remarked in his journal on the number of Aboriginal fires he saw around him. I saw many Native Fires in the faces of the neighbouring Mountains, he wrote, a sentiment echoed in 1820 by Pitt Water pioneer James Gordon. Are there many natives in the Interior? Commissioner Bigge asked him. I believe there are a good many from the fires that I have seen, Gordon replied.

Those images of an island alive with Aboriginal families around their campfires are haunting, for it had been so for at least 35,000 years. Yet to extinguish them for ever took British rapacity just thirty-five.

Baptised in Blood, Robert Cox

The natives say when a relative dies they give themselves up to grief. They break their spears and mourn.

George Augustus Robinson

Contents

Appendices

Black Tom Birch, or Kikatapula, the subject of this biography, is a paradox in Tasmanian history. Born and raised as a traditional man among his own people, in late adolescence he becomes a member of a prominent settler family in Hobart and is baptised into the Anglican faith. Upon the outbreak of the Black War, however, he returns to his people and becomes the most feared Aboriginal man in the colony. He leads many daring raids on settlers and is known to kill with alacrity. Yet whenever he is arrested and taken into custody, he is always released and no charge of murder is ever prosecuted.

Then at a critical moment in the war, he changes sides. He joins Gilbert Robertsons roving party and facilitates capture of the guerrilla leader Umarrah. He then becomes a leading member of G.A. Robinsons friendly mission and plays an important role in the diplomatic initiative to secure the surrender of the highly respected chief Tukalunginta. When he dies five months later, Robinson is deeply saddened at the loss of a close and valued friend.

Kikatapula is clearly an important player in the Black War, yet in comparison with Musquito, who was his mentor, and Umarrah and Manalakina and the other members of Robinsons mission such as Wurati and Trukanini, we know very little about him. What we do know is mired in controversy. Was he a small boy or a young man when he joined the Birch family in Hobart? Was he the ringleader of the killings at Grindstone Bay in 1823 or was he not there at all? Was he a witness to the massacre of his people at Bank Head Farm in 1826? What were the circumstances that led him to change sides in 1828?

Robert Cox has spent several years tracking down every known skerrick of information about Kikatapula in order to understand the apparent paradox in his life. What emerges is a riveting portrait of a Tasmanian Aboriginal man who through force of circumstance becomes the leading patriot of his people and his country. In this role he is driven by a grim determination to force the colonial invaders from his homeland. Yet at a critical moment his patriotism transforms him into a champion of reconciliation.

Coxs compelling portrait of Kikatapula enables the reader to compare him with other patriotic leaders in the colonial world such as Xanana Gusmo in East Timor and Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya. Like Kikatapula, they were Christians who through force of circumstance became leaders of their Indigenous communities and conducted guerrilla wars of resistance against colonial invaders. And like Kikatapula, at a critical moment in the struggle they also became champions of reconciliation. In locating Kikatapula in such august company, we can begin to understand him not as a paradox but as a true patriot whose paramount purpose was to save his people from extermination.

Broken Spear is the first biography ever written of this most important Tasmanian patriot and is especially important for that and because he was not only the man who sparked the Black War but the most feared, effective, and enduring Aboriginal leader, one whose resistance did not cease even after he changed sides. The book is destined to become a classic of our time and I am honoured and delighted to write the Foreword.

Professor Lyndall Ryan, AM FAHA

University of Newcastle

Author of The Aboriginal Tasmanians and The Tasmanian Aborigines Since 1803

His is an untold story, although he was catalyst for and chief prosecutor of a major war in which much blood, white and black, was spilt on Australian soil. His struggle made him a seminal figure in our history and one of the most influential people in colonial Australia, yet few people have heard of him, most historians have not noticed him, and even those few scholars who have bothered to look have not seen him clearly or wholly. Serious wrong has been done to Black Tom Birch and his rightful place in history.

He was once the most feared and hated man in Van Diemens Land. His rage at Britons savage treatment of his people, theft of Aboriginal lands and resources, abduction and enslavement of Aboriginal women and girls, and wanton destruction of the race and its culture sparked a bloody guerrilla campaign that quickly exploded into all-out war: the Black War of 18241831, which has been summarised by one historian as per capita one of the most destructive wars in recorded history.

Black Toms leadership in that war was so devastating that one newspaper demanded he be lynched immediately on capture. Yet despite being three times in British custody he was neither lynched nor punished in any other way. Eventually he changed sides to aid the enemy, first as a guide for an armed party sent to round up Aborigines for incarceration (or to kill those who resisted), then as guide and interpreter for an expedition undertaking one of the longest and most gruelling but least-known treks in Australian history as it sought to conciliate, and eventually to capture and incarcerate, every Aborigine remaining in the island. He died while ostensibly assisting his former enemies with this final roundup of his people for exile on a Bass Strait island, although in reality he was surreptitiously and successfully undermining British efforts. He then became the first person, Aboriginal or European, to be buried with Christian rites in the embryonic city of Burnie. For despite his bloody record, Black Tom Birch professed Christianity. Such incongruities sundered his short life.