Table of Contents

This is number twohundred and two in the

second numbered series of the

Miegunyah Volumes

made possible by the

Miegunyah Fund

established by bequests

under the wills of

Sir Russell and Lady Grimwade.

Miegunyah was Russell Grimwades home

from 1911 to 1955

and Mab Grimwades home

from 1911 to 1973.

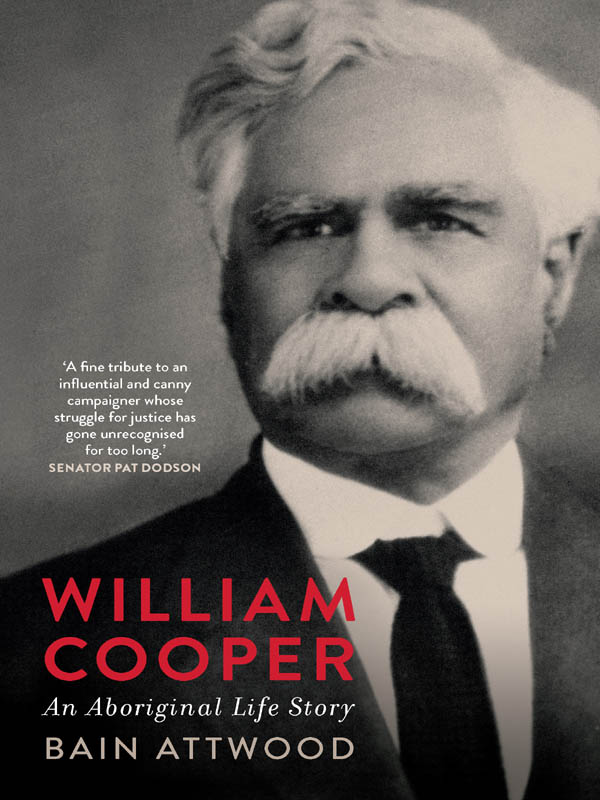

I have long been an admirer of William Cooper. He plumbed the pulses of political power to advocate for his people and for the Com-monwealth to manage Aboriginal Affairs. Bain Attwoods meticulously researched biography is a fine tribute to an influential and canny campaigner, whose struggle for justice has gone unrecognised for too long.

Senator Pat Dodson

A remarkable biography of a remarkable man. Meticulously researched and deeply reflective. Bain Attwoods biography of William Cooper is a rare example of a political life told in its full historical context.We see not only Coopers extraordinary struggle for his people but the entire network of activists that inspired him. Its hard to think of a biography that speaks as urgently and powerfully to Indigenous Australians long campaign for social, economic, and political justice.

Mark McKenna, Emeritus Professor, University of Sydney,

Honorary Professor, Australian National University

THE MIEGUNYAH PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2021

Text Janet McCalman, 2021

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover design by Philip Campbell Design

Typeset in 12/15pt Bembo by Cannon Typesetting

Cover image courtesy Alick Jackomos collection, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522877939 (paperback)

9780522877946 (ebook)

For the members of the Cooper family

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

O n saturday 7 August 1937 an unusual event occurred. An Australian newspaper published a feature story about an Aboriginal man that was based on an interview one of its leading journalists had conducted with him. The Australian press often ran stories about the blacks or the Aborigines, but it was unprecedented for a newspaper to commission a staffer to seek out an Aboriginal man and write a major story in which his own words were quoted at length and his views represented faithfully. The article even included a photo of its subject, while notice of its publication was given in the pages of the newspaper the day before it appeared.

The Aboriginal man was William Cooper. In his seventy-sixth year and living in a humble workers cottage in Footscray, he was the secretary of an organisation called the Australian Aborigines League. The occasion? Word had got around that Cooper was giving serious consideration to whether the time had come for him to present to the Australian Government a petition to the British king that he had drawn up and begun to circulate among Aboriginal people four years earlier.

The journalist was a young poet and writer, Clive Turnbull, whom many regarded as the doyen of Melbournes newspapermen. In September 1933 his newspaper, the Melbourne Herald, had published a report about Coopers petition. It was short but boldly headlined: MHR for Natives. King to be Petitioned: Unique Move. Australias native racethe aboriginesis taking steps for the first time in its history to secure from the King representation in the Federal Parliament, the reporter had noted before going on to explain: This is demanded as a right in a petition which is being circulated for signatures.

Now, four years later, Cooper told Turnbull that he hoped to see a change for the better before he died and that he was doing all he could to bring this about. Taking down a great roll of signatures on the petition, he observed: If we cannot get full justice in Australia we must ask the King There are 2000 signatures here, from aborigines all over Australia. Pointing to one of the pages of petition, Cooper added: Those who could not sign their own names have made their marks.

The petition called on the British king to intervene on the behalf of Aboriginal people in order to help prevent their extinction, provide better conditions, and grant them the power to propose someone to represent them in the federal parliament. Cooper explained to Turnbull: Up till the present time the condition of the aborigines has been deplorable. Their treatment was beyond human reason. Cooper believed the incumbent federal government was the first in Australia to take up the cause of his people. But it is not enough, he observed. In his view a tradition of cruelty had been handed down from white generation to generation to the present day. He confessed to Turnbull, I sit here working hour after hour in correspondence with my people thinking. How can we save them? He demanded to know what was being done for the principal needs of his people. We talk to politicians, and they say, Yes, theyll do this, and do that, but the years go on, and what is done?

Cooper sketched out for Turnbull the goals of the Australian Aborigines League, which he had founded in 1933, emphasising the importance of the fact that it was an Aboriginal organisation: You may read the views even of sympathetic white men. But they are not our views. For Cooper, the reason for this was clear: We are the sufferers; the white men are the aggressors. He explained what he meant: instead of lifting up our people the early comers to our country destroyed them. This had lasting consequences. Now our people have nothing: all was taken from them. They will never have anything so long as the present state of things endures. Aboriginal people today, he went on, have a horror and fear of extermination. It is in the blood, the racial memory, which recalls the terrible things done to them in years gone by. As far as he was concerned, the government had a duty towards the countrys original peoples. You may ask where is the money to come from. But we have lost countless millions to the whitesthe whole wealth of Australia. Are we not entitled to this? This was a constant theme in Coopers political work.

Turnbull was a sympathetic listener. Had he not been, we would not have this unusually rich testimony. We do not have to search far to understand why this was the case. I went to talk to him, Turnbull explained to his readers, because I have long been interested in the problem of the aborigines. This was so, he went on, because my own countrymen in Tasmania by a combination of cruelty and stupidity, succeeded in exterminating a whole race within 75 years.