Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

For Erica and Elijah

INTRODUCTION

N OVEMBER 5 , 1943 Pvt. Edward Butler, a Black soldier in the US Army, sent a letter back to the United States from North Africa. Written on the militarys standard Victory Mail stationery, the letter was not to a sweetheart or family member, but to someone he had never met, an elementary school social studies teacher in Chicago, Illinois, half a world away. The letter read:

Dear Mrs. Morgan,

I just read an article about you and your work I writting [sic] to you to find out if I can get a copy of the Negroes History which was mention in Newsreel Magazine it is something I didnt learn in school. But would like to learn it now Ill be glad when we are called Brown Soldier instead of Negrosoldier We are fighting and working for the same cause as every one [else] from the States

Your[s] Until,

Edward

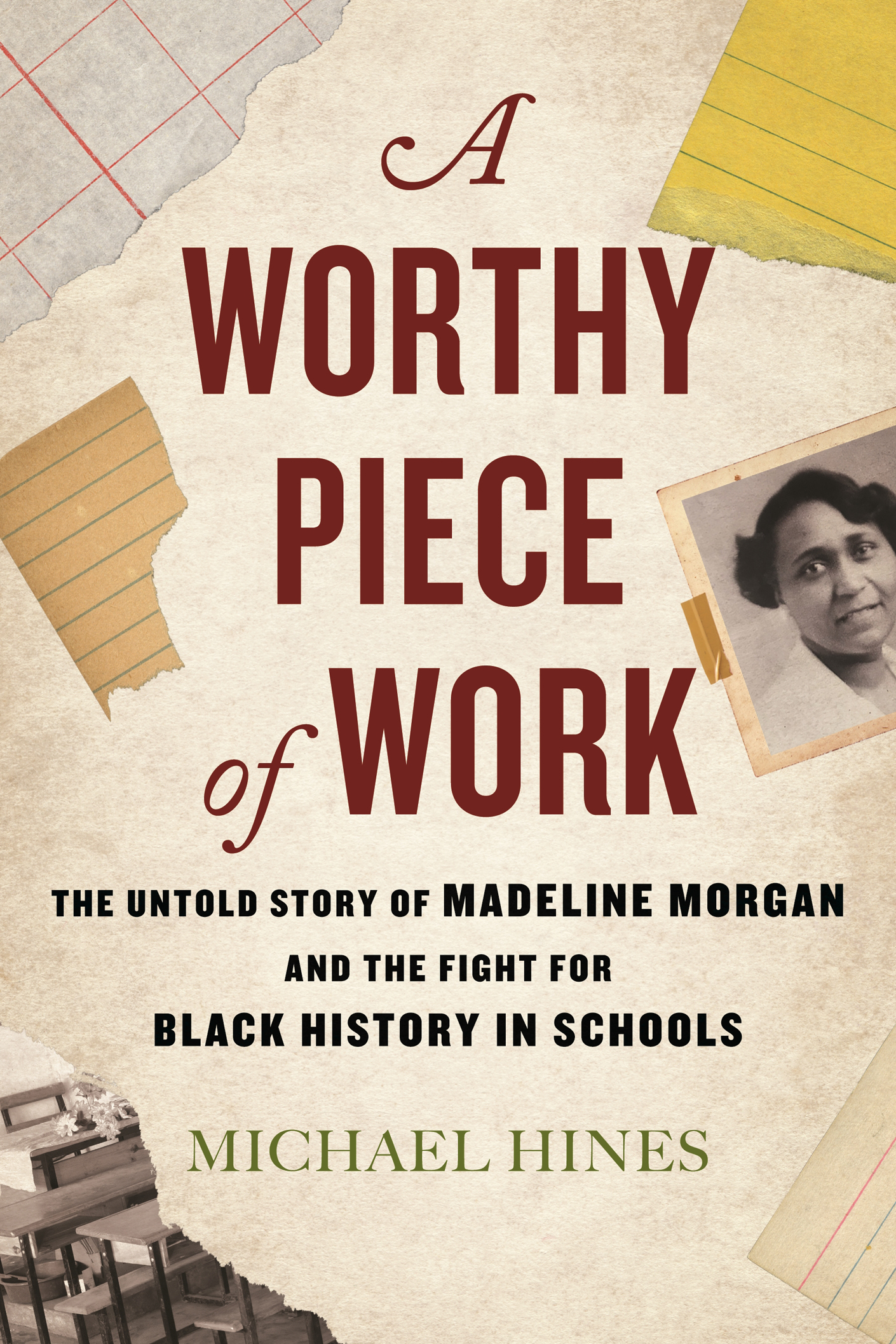

Butlers wartime request seems strange at first, but he was not alone in finding Madeline Morgan (later Madeline Stratton Morris) and her Negroes History worthy of attention. Throughout the war years, hundreds of soldiers and civilians, principals and teachers, colleges and commissions, parents and students eagerly sought out Morgan and her pioneering work in Black history. By the spring of 1944, just a year after Butlers correspondence, Morgan shared that hundreds of letters have been received expressing a desire to know something about the contributions of the Negro. The teachers writing appeared in Black academic journals like the Wilberforce Quarterly, Journal of Negro Education, and Negro History Bulletin, as well as predominately white publications like the Elementary English Review, and even popular news magazines like PM and Time. The ideas and ideals of the primary schoolteacher from Chicago traveled as far south as South America; as far north as Maine; as far west as California; as distant as Italy and Africa, and even to the United States Office of Education in Washington D.C.

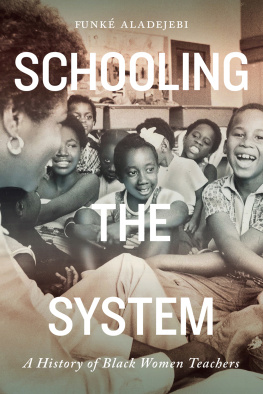

The reason behind the widespread interest in Morgans work from educators, scholars, and individuals like Pvt. Butler was that she had succeeded in spearheading one of the most profound educational efforts of the war years. Morgan had led a movement that resulted in the institution of Black history as part of the curriculum of Chicagos public schools, then the second largest school system in the nation. Her work, The Supplementary Units for the Course of Instruction in Social Studies, constituted an intellectual campaign against the foundations of American racial prejudice as bold and as necessary as the military effort to confront fascism abroad.

Hailed by Frayser Lane, civic director of Chicagos Urban League, as one of the finest approaches to improvement in racial relations ever attempted, the units included the histories of West African civilizations and their connections to Black culture in the Americas and elsewhere, depictions of slavery that addressed the horrors of the Middle Passage and the plantation system, the stories of Black soldiers who defended democracy even while being denied its fruits, and the biographies of Black artists, politicians, activists, and social leaders from the countrys founding to the present day.

Morgans work served as a model for cities and school districts across the nation, and she advised politicians, religious and civic leaders, and educators interested in the promotion of racial tolerance throughout the mid-1940s. Despite her notoriety during the war years, however, she has received little scholarly attention in the almost century since. Compelling but incomplete glimpses of her appear in larger volumes on race and education, womens activism, and public history. Yet a substantive work that explains her evolution as an educator, her success as a curriculum reformer and activist, and her legacy in the present has not yet been attempted. A Worthy Piece of Work addresses this absence, situating Morgan and her contributions within education during the 1930s and 1940s that garnered her national and international attention, within the broader movement for Black history and culture and the rise of pluralist and intercultural education during the Second World War.

The Early Black History Movement and the Alternative Black Curriculum

Morgans efforts in the Chicago schools were part of a larger wave of scholarship and activism aimed at the preservation and promotion of Black history in the early twentieth century, an intellectual and social project that historian Pero Dagbovie terms the early black history movement. Although Black Americans efforts to record and remember their past stretched back to the antebellum period, the years between 1915 and 1950 saw these early efforts expand, becoming highly organized and institutionalized. Carter G. Woodson, the Harvard-trained historian and educator remembered as the Father of Negro History, both personified and precipitated this shift. In 1915, Woodson launched the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which, through its yearly conferences and its publications, the Journal of Negro History and the Negro History Bulletin, centralized and systematized the study of the Black past. At the same time, Negro History Week (the precursor to Black History Month), an annual campaign created under the auspices of the association, brought Black history into communities and classrooms, making the associations work broadly accessible.

Negro History Week, which Woodson described as one of the most fortunate steps ever taken by the Association, revealed a major concern of the early Black history movement, the fight to reshape the school curriculum to which Black children were exposed.

Aware that Americas schools distorted history in order to uphold the logic of white supremacy, Black historians, educators, and activists created their own textbooks, magazines, lesson plans, childrens books, and other instructional materials. Scholar Alana Murray names these efforts the alternative black curriculum, a powerful term I adopt here to refer broadly to the pedagogical counter narrative created by Black scholars in order to provide a more accurate rendering of US and world history in the United States. Woodson and the association were critical to the flowering of the alternative Black curriculum, and Woodson himself authored several groundbreaking textbooks including The Negro in Our History (1922), The Story of the Negro Retold (1935), and African Heroes and Heroines (1939), each of which influenced generations of students and teachers.

In recent years, scholars have begun to shed light on both the early Black history movement and the alternative Black curriculum.

A Worthy Piece of Work advances and critically expands our understanding of the history of Black women educators and their role in building the alternative Black curriculum in schools, taking Murrays original focus on the period from 1890 to 1940 and extending it into the pivotal years of the Second World War and beyond. Morgans critique of the racism embedded in the official knowledge of Americas schools exemplified the alternative Black curriculum, yet her race, gender, and position as a classroom teacher have led to a lack of scholarly engagement with her ideas. In the chapters that follow, I trace her development as an educator, the scope and content of her major curricular innovations, and the substantial gains as well as limitations and constraints she met with. To do so, I draw on the techniques of educational biography to make clear the intersections between human agency and social structure that defined Morgans life and work. Throughout, I consciously center Black women who have remained marginal in most works written on the early Black history movement. This includes not only Morgan but a constellation of other figures, such as librarians Vivian G. Harsh and Charlemae Rollins, principal Maudelle Bousfield, and teacher activist Onedia Cockrell, each of whose stories intersects with Morgans own.