ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS IN THE TEXT

BYP 100 Black Youth Project 100

CAPTS Community, Administration, Parents, Teachers, and Students decision-making model

CBUC Chicago Black United Communities

CCCO Coordinating Council of Community Organizations

CIBI Council of Independent Black Institutions

CORE Congress of Racial Equality

CPS Chicago Public Schools

CTU Chicago Teachers Union

CUL Chicago Urban League

ESAA Emergency School Aid Act

ESEA Elementary and Secondary Education Act

FLY Fearless Leading by the Youth

FTB full-time basis substitute

HEW U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

HPKCC Hyde ParkKenwood Community Conference

IPE Institute of Positive Education

LSC Local School Council

NAACP National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

NCDC New Concept Development Center

PCC Parent Community Council

PCER Peoples Coalition for Education Reform

P.O.W.E.R. People Organized for Welfare and Employment Rights

PURE Parents United for Responsible Education

PUSH People United to Save [later Serve] Humanity (Operation PUSH)

SCLC Southern Christian Leadership Conference

SNCC Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

TWO The Woodlawn Organization

UIC University of Illinois at Chicago

WCB Woodlawn Community Board

WESP Woodlawn Experimental Schools Project

A POLITICAL EDUCATION

INTRODUCTION

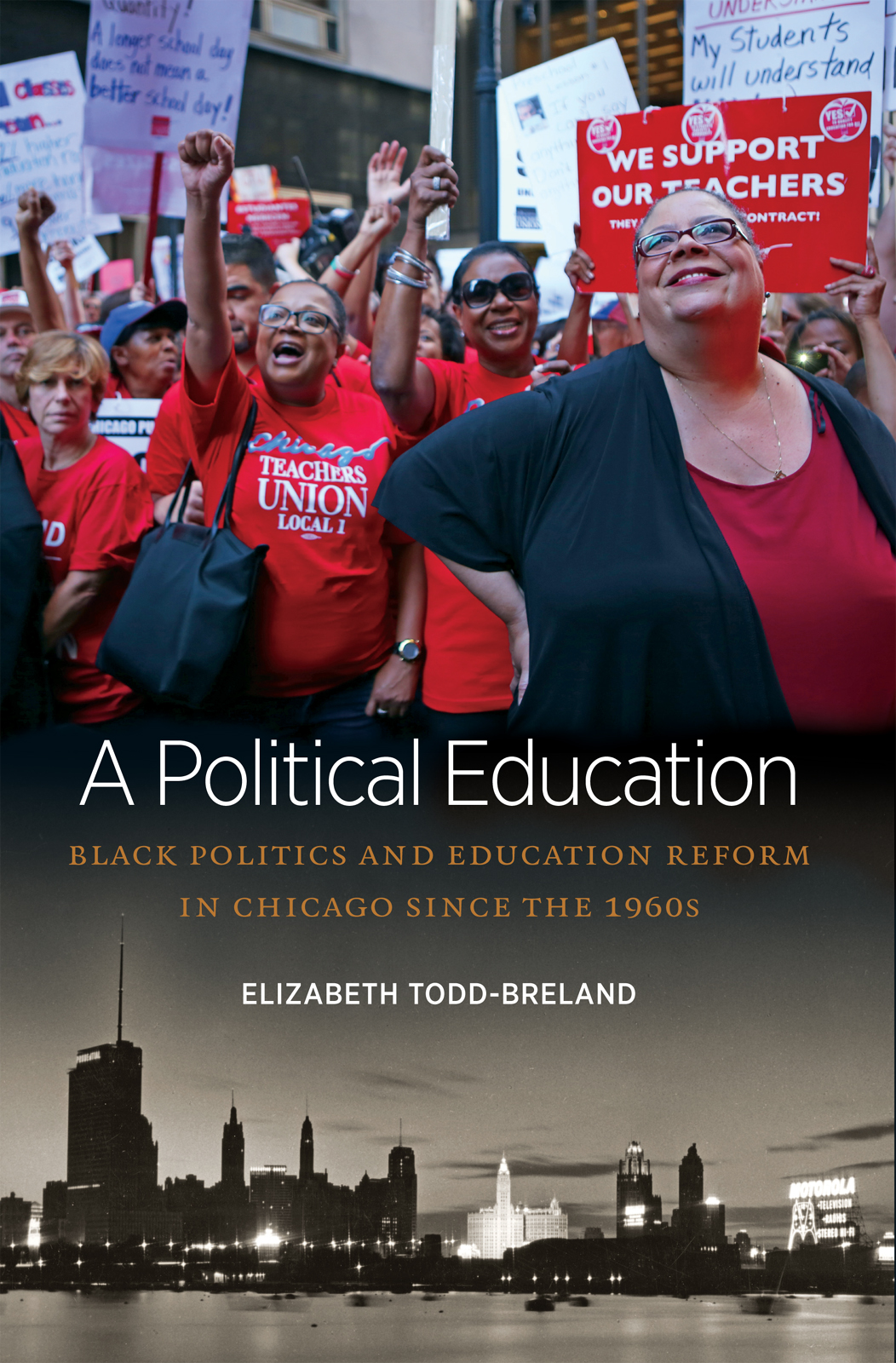

For seven days in September 2012, the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) shut down the City of Chicago. Of the CTUs more than 26,000 members, almost 90 percent had voted to authorize the strike. Thousands of striking teachers, community activists, parents, students, and supporters flooded the streets in protest. A sea of red shirts surrounded City Hall and Chicago Public Schools (CPS) headquarters.

In a city known for its long history of residential segregation, it was an incredibly diverse group: people of color and White folks, womenlots of women!and men, young teachers and older veteran teachers. Teachers and parents marched while pushing strollers and holding little ones hands. Together they chanted: Lies and tricks will not divide, Parents and Teachers side by side! Led by Karen Lewis, CTU president and a veteran Black educator, the teachers on strike in Chicago mirrored the core of the Democratic Partys electoral base, a racially diverse, traditionally Democratic group of middle-class public sector workers. These were the people who show up to the polls and vote. Were it not for the picket signs attacking Chicagos Democratic mayor Rahm Emanuel, one could easily mistake the assembled group for attendees at a rally for Barack Obamas presidential reelection campaign. But impressive as the sea of red shirts may have been, a year later the carcasses of nearly fifty shuttered schools in predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods were just as striking.

The year that started with the citys first teachers strike in a quarter century ended with the largest intentional mass closure of public schools in U.S. history. The leaders who shaped these bookend events represented starkly different political traditions. Karen Lewis drew upon sustained community organizing efforts in the citys predominantly Black and Latinx communities. The striking teachers and their supporters were both protesting the anti-union privatization policies of the local Democratic administration and calling for resources to address the enduring structural inequities that relegated Black and Latinx students to separate and unequal schools. Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel, a former investment banker, congressman, and presidential aide to Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, insisted that the logic of corporate reorganization and the market necessitated school closures to remedy the struggling system. These colliding political currents were the product of enduring and unresolved struggles over urban racial politics and education reform.

A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s recovers and exposes this history. This book analyzes Black education reformers community-based strategies to improve education beginning during the 1960s and shows how these efforts clashed with a burgeoning neoliberal educational apparatus during the late twentieth century. The historic 2012 CTU strike and the massive school closures that followed laid bare the ruptures resulting from this painful collision.

Black education organizing presents an opportunity to examine the possibilities and constraints of neoliberalism as a conceptual frame for the period since the fiscal crises of the 1970s. Though neoliberalism at times seems to encompass everything and nothing, here it describes the significant economic restructuring that has shaped life since the 1970s, with roots stretching back decades earlier. Naomi Klein uses the term corporatism to describe the many features that characterize these shifts in the Global North: the transition from an industrial economy to a service economy, the rise of finance capitalism, and the intensified consolidation of money and power by a small group of political and corporate elites. In this political and economic realignment, crises real and imagined pave the way for dramatic economic and social restructuring based on the policy trinitythe elimination of the public sphere, total liberation for corporations and skeletal social spending. This economic restructuring profoundly impacted the realm of education where corporate and political elites have projected a perpetual state of educational crisisof funding, achievement, and pedagogyto justify the transfer of public funds to private entities, attacks on teacher unions, divestment from funding universally accessible high-quality public education, and the embrace of market-based competition and choice by private sector actors, state officials, and corporate education reformers. This era of neoliberalism affected the context in which the actors in this book operated.