This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1958 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

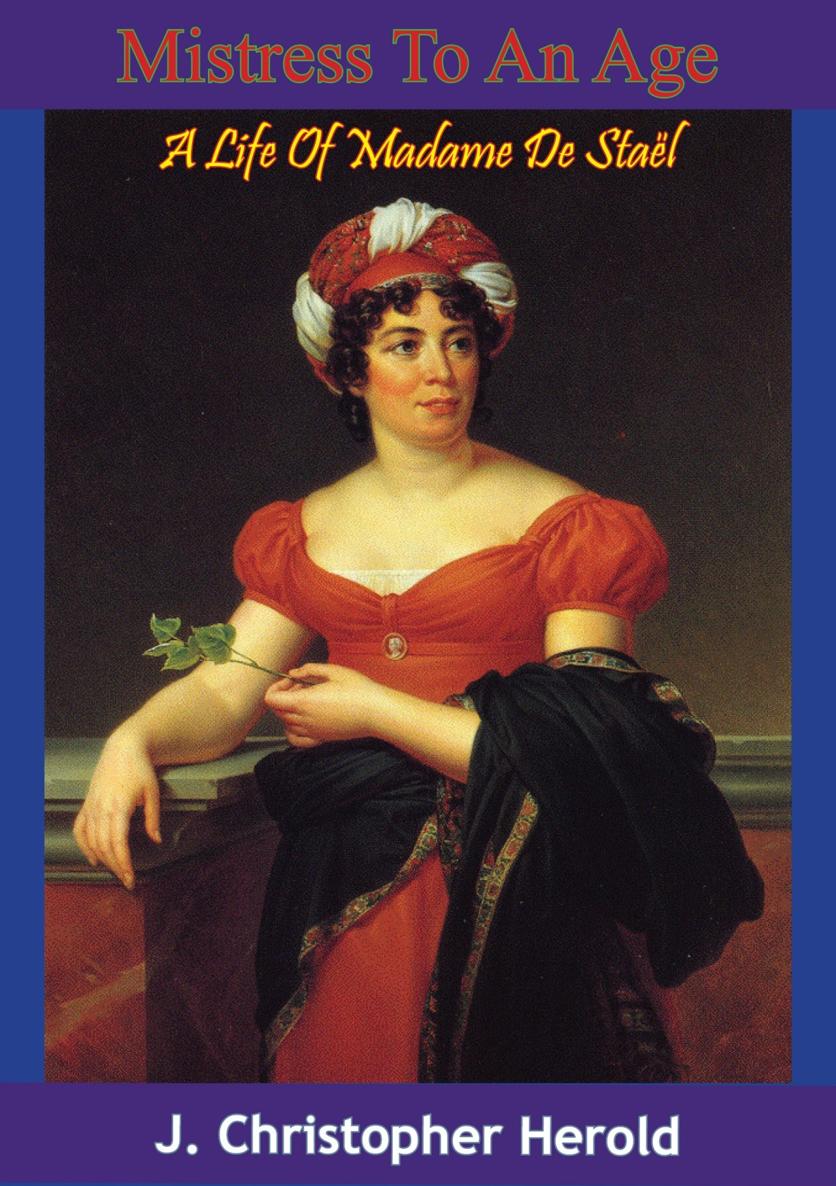

MISTRESS TO AN AGE:

A LIFE OF MADAME DE STAL

BY

J. CHRISTOPHER HEROLD

PREFACE

THIS WORK is not offered as a definitive biography. In the first place, despite the impressive literature and documentation already published on Madame de Stal and her friends, a still larger mass of material remains unknown; in the second place, definitive biographies can be written only about people who are quite dead. Sometimes, to be sure, they still show some feeble signs of life, but the definitive biographer gives them the coup de grce.

At the end of the last century, Lady Charlotte Blennerhassett wrote a splendid three-volume work on Madame de Stal which almost might have been definitive. It is an impressive work, and still a very useful one. It almost buried Madame de Stal. Madame de Stals mother, who had an obsession about precipitate inhumations, hoped to escape that fate by having herself preserved in a basin of alcohol and visited daily by her husband; Madame de Stal herself, who observed on that occasion that this was not the way in which she proposed to be remembered, was much too alive to stay buried after Lady Blennerhassett had embalmed her. She never ceased to protest her untimely burial: long-hidden documents turned up, and still are turning up, still-living witnesses to her passions and to the passions she inspired; scholars reread her works with a fresh eye for the vigor and originality of her intelligence; others, studying the lives of her great contemporaries who also were her friends and enemiesa Napoleon, a Byron, a Talleyrand, a Goethe, a Chateaubriandconstantly found her on their path and often enough let her divert them from it. Thus a new Stalian literature sprang up, investigating special aspects and relationships and making public a number of revealing documents: letters, diaries, manuscripts, police reports, and the like. These aspects and relationships were, however, as manifold as the documentation was overwhelming, encompassing not only Madame de Stals labyrinthine and astonishing love life but also the political and intellectual history of Europe from the eve of the French Revolution to the first years of the Bourbon Restoration, not to mention the literatures of several nations. Those who wrote on Madame de Stal, if they wrote at all seriously, limited themselves to some specific aspect or relationship. When I began this work, enough had been published to convince me that a new synthesis was not only possible but also desirable; I therefore made it my task to write a general biographynot a definitive biography, which merely would bury Madame de Stal once again, and unsuccessfully at that, but a fully rounded one, which would restore her to life in the public mind.

To this conviction there soon was added another: to write an exhaustive account of Madame de Stals life would not only exhaust the biographers own life but also would require a kind of mind and temperament that had no affinity whatsoever with the type of intellect that was Madame de Stals. Writing the present work was an exhausting enough task: but throughout it I felt sustained by an intellectual sympathy and a similarity of interests with the subject of the biography. In my attempt to unravel and understand the life of her passions, I remained a fascinated spectator, always trying to understand yet refusing to be swept along; but in discovering her thought, I found myself an active partner in a conversation, a conversation in which I became aware, almost at first hand, of her supreme powers in that art, and in which she often helped me to find my own convictions, for which I had long been groping. Decidedly, Madame de Stal is not dead.

In my labors, a number of persons have assisted and obliged methough not nearly as many, I regret to say, as I had hoped. Some of the persons who assisted me most were dead long before I was bornamong them Mme Necker de Saussure, M. Saint-Beuve, and others whose writings are listed in my bibliography. I am particularly indebted to them for the easy grace with which they put their materials and knowledge at my disposal.

Among the living, I am indebted first of all to the Comtesse de Pange, Madame de Stals great-great-granddaughter, for the encouragement she gave me when I began my project, an encouragement without which I might never have pushed it very far; I am equally indebted to her, as are all Stalian scholars, for her profound researches and for her liberality in making family documents available: no person has done more than she for the revival of Stalian studies. I also wish to extend my most heartfelt thanks to Professor Donald M. Frame of Columbia University, who carried out a difficult mission at the New York Public Library with immense sagacity and precision; to Dr. John D. Gordan, of the New York Public Library, for giving me permission to use Madame de Stals unpublished letters at the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection; to Professor Bengt Hasselrot of Uppsala, for his kind and warm encouragement and for producing, with miraculous speed and at a critical moment, a portrait of Eric Magnus Stal von Holstein; to Mr. Daniel Eaves, for drawing my attention to a virtually unknown portrait of Madame de Stal at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco; to Mrs. Florence Yao Chu, of the Library of Stanford University, for her patient and efficient magic in obtaining books from libraries all over the world; to my wife Barbara, for putting up with Madame de Stal for five years and for typing five thousand pages; and to my exasperating editor, Mr. Stephen Zoll, for being exasperating.

Professor Pierre Kohler of Berne, at the outset of my labors, gave me advice which proved extremely wise and helpful.

I feel an immeasurable debt of gratitude to the authors and editors of the following works, as well as to their publishers: E. Beau de Lomnie, ed., Lettres de Madame de Stal Madame Rcamier (Paris: Domat, 1952); Georges Bonnard, ed., Le Journal de Gibbon Lausanne (Lausanne: F. Rouge & Cie., 1945); Paul Gautier, Madame de Stal et Napolon (Paris: Plon, 1903); Othenin, Comte dHaussonville, Le Salon de Madame Necker (Paris: Calmann-Lvy, 1882) and Madame de Stal et Monsieur Necker (Paris. Calmann-Lvy, 1925); R. L. Hawkins, Madame de Stal and the United States (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1930); Pierre Kohler, Madame de Stal et la Suisse (Lausanne and Paris: Payot, 1916); E. Lavaquery, Necker, fourrier de la Rvolution (Paris: Pion, 1933); Maurice Levaillant, Une Amiti amoureuse: Madame de Stal et Madame Rcamier (Paris: Hachette, 1956); Jean Mistier, Madame de Stal et Maurice ODonnell (Paris: Calmann-Lvy, 1926); Jean Mistier, ed., Lettres un ami (Neuchtel: A la Baconnire, 1949); J, E. Norton, ed., The Letters of Edward Gibbon (3 vols.; London: Cassell, 1956); Comtesse Jean de Pange, Madame de Stal et Franois de Pange (Paris: Pion, 1925), Monsieur de Stal (Paris: Editions des Portiques, 1931), and A.-G. Schlegel et M me de Stal (Paris: Albert, 1938); Alfred Roth and Charles Roulin, eds., Journaux intimes de Benjamin Constant (Paris: Gallimard, 1952).