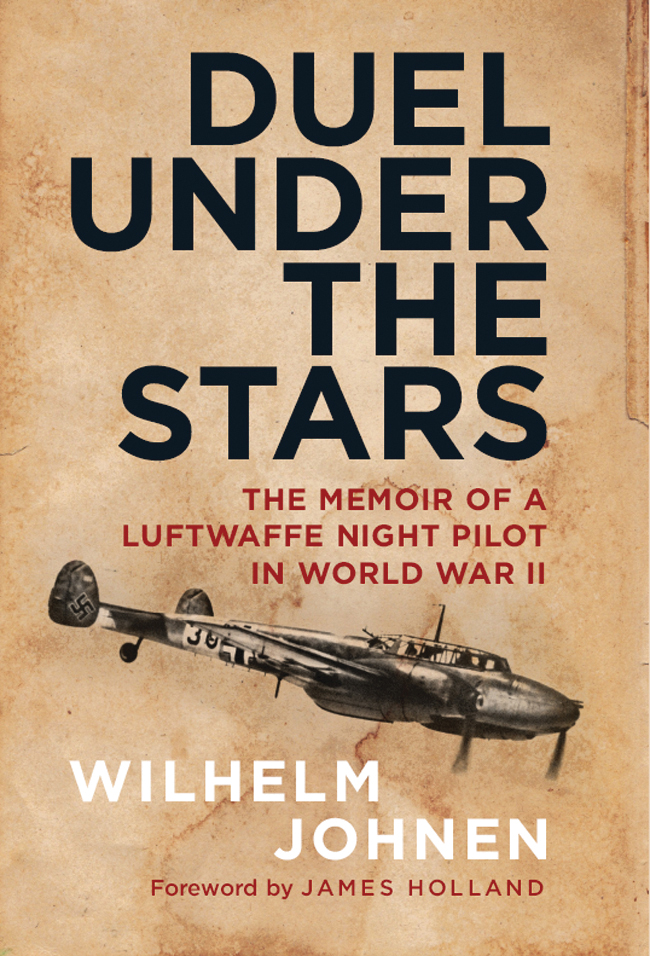

D UEL UNDER THE S TARS

Oberleutnant Wilhelm Johnen before promotion to Hauptmann.

D UEL UNDER THE S TARS

The Memoir of a Luftwaffe Night Pilot

in World War II

Wilhelm Johnen

Foreword by James Holland

Duel under the Stars: The Memoir of a Luftwaffe Night Pilot in World War II

This edition published in 2018 by Greenhill Books,

c/o Pen & Swords Books Limited, 47 Church Street,

Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.greenhillbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-78438-258-2

eISBN: 978-1-78438-260-5

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-78438-259-9

All rights reserved

Foreword James Holland, 2018

Main text 1956 by Richard Brenfeld Verlag, Dsseldorf

Wilhelm Johnen

2009 Verlagshaus Wrzburg GmbH & Co. KG

Flechsig Verlag, Beethovenstrae 5 B, D-97080 Wrzburg, Germany

( www.verlagshaus.com )

Translation Greenhill Books, 2018

Publishing History

Wilhelm Johnens memoir Duell unter den Sternen: Tatsachenbericht eines deutschen Nachtjgers 19411945 was first published in Germany in 1956. The first English-language edition of Duel under the Stars was published in 1957 by William Kimber.

This new English-language edition includes new introductory material from James Holland and new photographs

Photographs were made available by: Princess Walburga of Sayn-Wittgenstein; Martha Schnaufer, Calw; Werner Streib, Mnchen; Flugkapitn Fritz Wendel, Augsburg; Dr Max Stpfgeshoff, Solingen; Dr H. Siecke, Blomberg Archiv der Stadt Ulm; Walter Doelfs, Freiburg; Imperial War Museum, London; Peter Kleu; D. J. Irving; Peter Spoden

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Foreword

For all the debate and discussion over both the efficacy and morality of the Allied strategic air campaign against Nazi Germany in the Second World War, there are few who could fail to be moved by the plight of the young crews sent to carry out the bombing. By the latter half of 1943, Germany was being bombed around the clock, by day by the Americans and by night by the British and Commonwealth bomber crews of RAF Bomber Command. The Americans faced intense flak from German day fighters; Bomber Command were pitted against flak, searchlights and radar-guided night fighters. The worst flak concentrations could be often avoided, however, except over the target itself, where crews had to fly straight and level and pray they would not be hit. It was, frankly, a massive lottery.

Lurking over the enemy skies, however, were growing numbers of German night fighters, which would stalk their prey like a dark panther then attack with overwhelming fire-power: a mixture of machine guns and 20mm and even 30mm cannons that tended to make very short work of any RAF bomber they managed to successfully creep up on. Knowing these hunters were out there meant that, once over enemy territory, the entire bombing raid was a time when nerves were stretched taut and fear preyed on the minds of those unfortunate enough to be given the task of dropping bombs on the enemy.

There are large numbers of memoirs, diaries and oral history interviews that testify to the relentless fear suffered by these men, and I cannot think of a single account or conversation I have had with a former bomber crew member that does not mention this grinding and ever-present threat. Even Guy Gibson, winner of the Victoria Cross and one of the most famous and decorated Bomber Command pilots of them all, repeatedly wrote of the extreme fear he felt. Eric Winkle Brown, the extraordinary test pilot, once told me that Gibson had confessed to him feeling utterly terrified every time he stepped into a Lancaster.

We are well used to referring to the Nazi war machine and regarding the wartime Germans as being masters of vorsprung durch technik. The Germans had the best equipment, best weapons, best technology, and no part of the Wehrmacht the Nazi armed forces represented that better than the Luftwaffe. This still widespread view has been resoundingly dismissed in recent years as the Nazis have been shown to be both woefully inefficient in many regards and neither so mechanically replete nor technologically advanced as perceived, despite the advent of jet power and rocket missiles later in the war. Despite this realignment, there remains an indelible view of the Luftwaffe as the cutting edge of the Wehrmacht, and through the memoirs and other testimonies of those who came up against them, the night fighter the nachtjagdflieger remains as one of the most Teutonic, mechanical and lethal of all. Even as I write this, it is hard not to picture in ones minds eye a lumbering Lancaster being preyed upon by a lithe German night fighter, bristling with weapons and looking all the more sinister for the complex array of radar aerials, making it appear like the giant mandibles of a killer spider attacking the victim caught in its web. At the controls, a squared-jawed, blonde-haired young Nazi: dashing, daring, deadly and devoid of mercy.

No doubt this is how they seemed and, of course, the experiences of Allied servicemen in the Second World War is, inevitably, far more familiar than those of the enemy. There are, however, a number of memoirs written by German veterans of the war, but only a very few have ever reached a wide audience and most have long since fallen out of print and, with it, obscurity. This is a great shame, because it is important to understand the human experience of war in the round rather than from the narrow prism of ones own national viewpoint.

It is, therefore, very good news that Wilhelm Johnens memoir, Duell unter den Sternen, first published in Germany in 1956 and then in English a year later, is being brought back into print. Johnen was one of those night-time stalkers of British bombers and a very good one too, with no less than eighteen confirmed victories. His is a fine account not of a Nazi automaton but of a young pilot whose fears, anxieties, triumphs and pain are every bit as human as of those he was fighting against.

The Luftwaffe was the only part of the German armed forces to have been created during the Nazi era, so it is perhaps understandable that it had the reputation for being the most Nazified part of the Wehrmacht. This may well have been true in broad-brush terms, but I have certainly read as many contemporary diaries that show clear contempt for the regime as I have of those who beatify Hitler. Johnens account, published a decade after the wars end, sensibly keeps politics out of it.

Moreover, as the book begins he cuts straight to the chase. There is no account of his childhood, or even what motivates him to join the Luftwaffe. It is implied, however; like many young aspiring pilots, the air force clearly represented glamour, excitement and the thrill of being part of an elite. Just eighteen when he joined the Luftwaffe, after gaining his wings he was posted in May 1941 to train as a night fighter, an intense six-week course. Almost the moment he arrived at Stuttgart-Echterdingen, he witnessed a trainee crew hurtle downwards from 6,000 feet up in the sky and explode into a million pieces. A good start, I thought, he noted ruefully. In a somewhat depressed mood we fledglings retired to bed. Training was rigorous and often counter-intuitive. Among the requirements was the learning of sixty consecutive hand movements blindfold and in the right order and with precision.

Next page

![Bar Wing Commander Guy P. Gibson VC DSO - Enemy Coast Ahead [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/180257/thumbs/bar-wing-commander-guy-p-gibson-vc-dso-enemy.jpg)