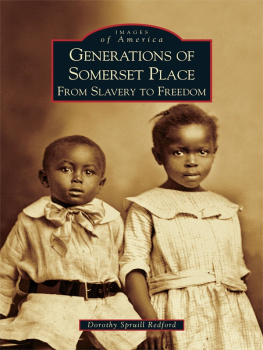

Somerset Homecoming

A Chapel Hill Book

First published by

The University of North Carolina Press in 2000

1988 by The Somerset Place Foundation

All rights reserved

Originally published by Doubleday

All illustrations are the property of

The Somerset Place Foundation unless otherwise noted.

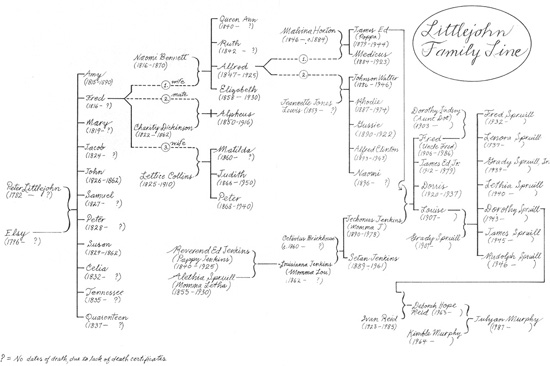

Family tree and maps by Michael Flanagan.

Set in Monotype Garamond and Bickham by Eric M. Brooks

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to

Senator Clarence W. Blount for permission to quote from

his November 1986 letter to Dorothy Spruill Redford.

Publication of this volume was aided by a generous grant

from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Redford, Dorothy Spruill.

Somerset homecoming: recovering a lost heritage /

Dorothy Spruill Redford with Michael DOrso.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Doubleday, 1988.

A Chapel Hill bookSer. t.p.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8078-4843-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Somerset Place (N.C.)History. 2. Somerset Place (N.C.) Biography. 3. Afro-AmericansNorth CarolinaSomerset Place History. 4. Plantation lifeNorth CarolinaSomerset Place History. 5. SlaveryNorth CarolinaSomerset PlaceHistory. 6. Redford, Dorothy Spruill. 7. Spruill family. 8. Family reunions North CarolinaSomerset Place. I. Title. II. DOrso, Michael.

F264.S68R4 2000

975.621dc2I 99-043644

CIP

13 12 02 11 10 09 5 4 3 2

THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY PRINTED.

Contents

Acknowledgments

A traditional saying among my people is Praise the bridge that carries you over. During the past eleven years, ever since Alex Haleys Roots inspired my search that culminated in the 1986 Somerset Homecoming, I have crossed many waterssome deep, some stagnant, some muddybut strong, supportive bridges were always there for me. Among them:

All of the scholars whose published works provided information, insight, and instruction and some who lent an ear and encouragement: James Proctor Brown (Norfolk State University), Eric Ayisi (College of William and Mary), and Peter Wood (Duke University).

The offices of the Clerk of Courts for Chowan, Tyrrell, and Washington counties in North Carolina.

The Sargent Memorial Room of the Kirn Library, Norfolk, Virginia.

The North Carolina State Archives and the staff of the Search Room, who assisted me in accessing the Josiah Collins family papers.

The Northeastern North Carolina Historic Places Office, which provided a grant to photocopy more than two thousand pages from the Collins Collection and house them at Somerset Place.

My friends in the Historic Sites Section of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, who worked tirelessly to ready the site and support the event.

The many journalists whose coverage of the Homecoming allowed the nation to share in the healing effects of the day. And one journalist in particular, Mike DOrso, features writer for the Virginian-Pilot and the Ledger-Star, through whose talents this volume was written. The staff of the Virginian-Pilot and the Ledger-Star, and especially the staff of the newspapers library, for their support of his efforts in writing this book.

My co-workers at the Portsmouth Department of Social Services and those other friends who on a daily basis applauded every small accomplishment and said, We are proud of you.

The strongest and most supportive bridges are family: my mother, father, brothers and sisters, and especially my daughter Deborah, for whom my love is unconditional, as is her love and support for me. And then there is our extended family of Somerset Place descendants, who made the Homecoming a true celebration of life and a reaffirmation of family.

Dorothy Spruill Redford

Beginnings

Daddy was at work the windy February morning I came to ask about Columbia.

He was seventy then and holding down three jobs. The granary was closed. Waldo had shut it down back in 1962, after he became the citys Commissioner of Revenue. But Waldo didnt leave Daddy jobless. He took him along, made him a janitor, and thats where my father worked for the next thirteen yearskeeping the Commissioner of Revenue offices clean.

They retired Daddy at sixty-five, but he wasnt the retiring kind. Hed been doing a mans work since he was twelve, and he wasnt about to sit down until he had to. So he got on as a runner at a local bank, was hired to clean a judges office, and clerked at a neighborhood hardware store. That was enough to keep his days filled.

Mother and he were living in town then, in Churchland proper, in a three-bedroom wood house Daddy built on land he paid for with some of his hogs. Six of us children were grown and gone. Rudolph, the youngest, was the only one still living at home. He was out, too, the morning I arrived to ask my mother who I was.

It was January 1977, a time when I had not been thinking much about the past.

I was thirty-three that winter, a single mother with a thirteen-year-old daughter. We lived in the South. Not the South of moss-draped oaks and whitewashed pillars the snapshot images that spring to the mind of those who have not lived there. No, Deborah and I were in Portsmouth, Virginia, a gray harbor-front town of ships and sailors. I was a social worker, supervising three welfare offices that handled about a hundred cases a day. That was a good number, high enough to keep us all busy, knowing our jobs were secure. Sometimes it bothered me seeing my work that way, knowing my good fortune depended on someone elses bad. But I worked hard, and I was good at my job, good enough to think about moving that winter from our rented apartment to a townhousethe first home Deborah and I would call our own.

My job, my daughter, and a mortgageI had plenty to think about but not so much not to know that the world was sitting down that week to watch Roots. At least the world I knew. It was all my friends and co-workers could talk about. They watched it at night and talked about it in the morningabout Africa, about slavery, about finding their ancestors.

I was too busy with the here and now to think about there and then. But I watched, too. And as I did, it all rushed back, feelings I hadnt faced in years. Emptiness, anger, confusion, denialmost of all, denial. For thirteen years I had tucked those feelings away, telling myself they no longer mattered. Now they were back again, but with a difference. It wasnt just me facing the questions now. Deborah wanted answers, too. She watched, and suddenly she was asking about things wed never talked about. Who were my great-grandparents? Where did they come from? Were they slaves? And their parents, where did they come from?

My daughter was demanding her past, but I could not give it to her without discovering my own. And that meant picking up where I left off the day Deborah was born. It meant going back to New York City, to Queens and Harlem, to Aunt Dot and Ivan. Back to Virginia, to my mother and father and sisters and brothers, to hogs in the pen and prayers in the living room. Back to North Carolina, to a hazy town of dirt streets and distant cousins, to the edge of the woods where the vaguest family memories and whispered stories stoppedand beyond which my own story began.