This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1959 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

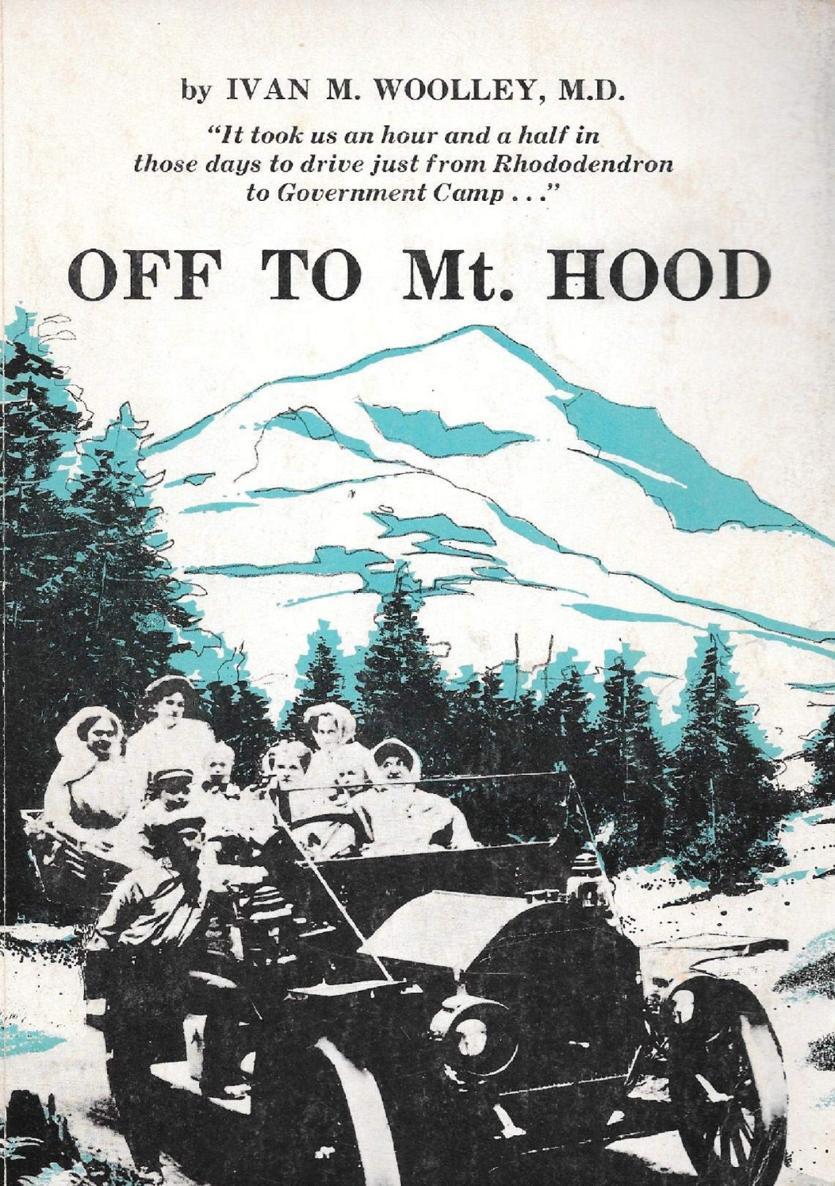

OFF TO MT. HOOD

AN AUTO BIOGRAPHY OF THE OLD ROAD

BY

IVAN M. WOOLLEY

OFF TO MT. HOOD

AN AUTO BIOGRAPHY OF THE OLD ROAD

IVAN M. WOOLLEY

THE OLD ROAD

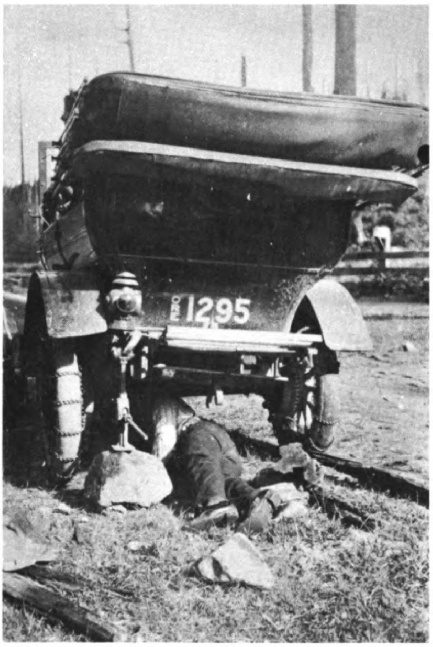

Hows the road? That was the question that was most frequently asked of us who drove the motor stages over the old road to Mount Hood. It was a question that had to be answered differently to different people. If it were asked by an old-timer who knew the road well, the answer was a simple good or bad. If the questioner was a stranger, one had to find out what he considered a bad road to be. If he were a person used to mud and dust, corduroy and plank, bumps, sand and rocks, with trees here and there that nudged in close to the ruts, it was easy to give him an idea of the conditions that prevailed for the particular day. If he were not used to such things, it was far wiser to change the subject, else you might lose a passenger before ever getting started.

The road improved a little each year, in places, particularly near Portland, but always it was a daily challenge until the State Highway Commission finally took over the old toll road and built a modern highway all the way to Government Camp, four miles below the timberline, and on around the south side of the mountain to eastern Oregon. To those of us who spent long hours fighting plank and mud, sliding continuously into the chuck holes and lifting out of them by a fast shifting of gears, only to repeat the process in another fifty feet or so, and grinding up hill after hill in low and second gear, it would not have seemed possible that some day people would drive the fifty-five miles from Portland to Government Camp in an hour and a half and never shift gear all the way. It took us an hour and a half in those days to drive just from Rhododendron to Government Camp, and the distance then was only nine miles instead of the eleven miles it is today.

The old road had its beginning as an Indian trail that crossed the Cascade Mountains on the southern slopes of Mt. Hood. It was narrow, steep, and in places, dangerous to travel. The early emigrant wagon trains enroute from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley of Oregon, encountered a bottleneck when they reached The Dalles, which was on the south bank of the Columbia River at the eastern portal of the formidable gorge that had been cut through the Cascade Mountains by this mighty river. There was no way to pass through the Gorge except by raft-like bateaux manned by oarsmen with long sweeps. The many rapids made this a hazardous passage and the scarcity of the craft caused long delays which were excessively costly to the hundred or more people usually stranded there. Food was scarce for man and beast and illness took a heavy toll.

When Samuel K. Barlow arrived at The Dalles in 1845, he studied the situation from several angles. The fees charged by the boatmen were high and this expense added to the cost of food and stock feed during the long time he would need to wait for his turn, would be a serious drain on his funds.

He learned that there were two Indian trails that crossed the foothills of the Cascade Range, one north of Mount Hood (Lolo Pass) and one south. Against all advice he determined to attempt the south trail. Consequently, on September 24 of that year he set forth with his seven wagons and nineteen people to attempt the crossing.

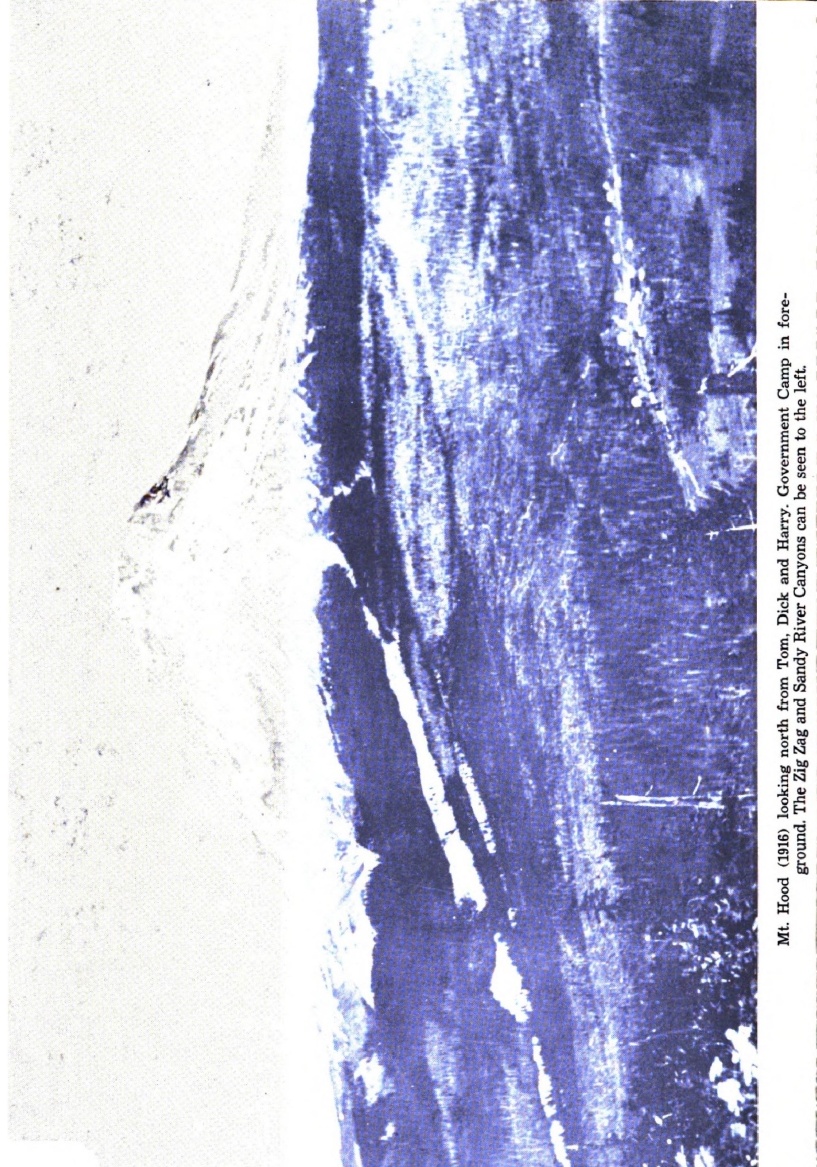

Shortly after Barlows departure, Joel Palmer arrived at The Dalles and, learning of the Barlow plan, decided to join him. With twenty-three wagons he left from The Dalles October 1 st , and the two groups joined forces along the White River. Palmer and Barlow acted as scouts and blazed the way for the crews who scratched out a track wide enough for the wagons. On the east slopes the going was not too bad since it was dry and the timber more sparse. Much of the clearing of brush and trees here was accomplished by burning. But at best, progress was slow and the season was growing late. Fearful that they might become snowbound, they decided to cache the wagons and heavy gear and press on over the summit into the valley.

Even thus relatively unencumbered they had difficulty. There were many treacherous swamps along the summit which caused delay and cost much physical energy in order to save their goods and their stock. Grass was scarce and some of the horses were poisoned by browsing on laurel (rhododendron). Cautious experimentation proving that the meat of the horses was not poisonous for human beings, and it was quickly added to their commissary. The food supply became so seriously depleted that it was evident it would not last until they could reach a supply source.

Barlows eldest son and two companions set out ahead to obtain help. Reaching the Sandy River they were unable to find a crossing. Young Barlow cut a pole and vaulted from rock to rock until he reached the opposite side. He continued on alone and was successful in organizing help in time to avert serious consequences. The party eventually arrived safe at Oregon City in the Willamette Valley. The territorial legislature was in session at Oregon City in December of that year and Barlow petitioned for a charter to open a road across the Cascades. The charter was granted December 16, 1845, as soon as the snow had melted, a party of forty men set out to recover the wagons that had been left behind and to clear the rest of the way. The construction of course was crude and skimpy, but Barlow operated it as a toll road for two years after it was opened.

Originally, the road was ninety miles in length, beginning near Wapinitia on the east slope of the Cascades, and ending a few miles south of the present town of Sandy, where it joined the old Foster Road. Barlow later deeded his rights to the government and the road was operated under lease for the next two or three years. The lease operators did nothing to improve or repair it and it deteriorated badly as a result.

In 1862, the Mt. Hood Wagon Road Company, capitalized at $25,000, took the road, but their operation failed. They were followed in May, 1864 by the Cascade Road and Bridge Company, Inc. This company laid some corduroy across the swamps, built some bridges and made other improvements. In 1862, the road was deeded to the Mt. Hood and Barlow Road Company, which was organized by Richard Gerder, Stephen Davis Coalman, H. E. Cross, J. T. Apperson, and F. O. McCown. This group shortened the road so that its western terminus was at Alder Creek, and they made some further improvements, but at its best it was still a rugged, formidable passage, particularly on the west side of the mountain.