All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright 1959 by Ernle Bradford

Cover design by Open Road Integrated Media

ISBN 978-1-4976-2573-0

This edition published in 2014 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.openroadmedia.com

Open Road Integrated Media is a digital publisher and multimedia content company. Open Road creates connections between authors and their audiences by marketing its ebooks through a new proprietary online platform, which uses premium video content and social media.

Videos, Archival Documents, and New Releases

Sign up for the Open Road Media newsletter and get news delivered straight to your inbox.

Sign up now at

www.openroadmedia.com/newsletters

FIND OUT MORE AT

WWW.OPENROADMEDIA.COM

FOLLOW US:

@openroadmedia and

Facebook.com/OpenRoadMedia

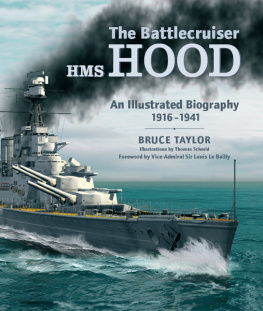

THE MIGHTY HOOD

ERNLE BRADFORD

We that survive perchance may end our days

In some employment meriting no praise;

They have outlived this fear, and their brave ends

Will ever be an honour to their friends.

Epitaph by Phineas James, Shipmaster,

To his stricken comrades (1633)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This history could not have been written without the help of the Record Office of the Admiralty. In particular, I am grateful to Mr. E. Hepworth and Mr. E. R. Holly for their long forbearance with my requests for records and information, dealing often with matters more than a quarter of a century old.

I would also like to acknowledge my debt to the library of the Imperial War Museum, and to Miss R. E. Coomb. In enabling me to gain a general picture of the background against which the Hood played her part for the twenty-one years of her life, her assistance was invaluable.

I am indebted to so many officers and ratings of the Royal Navy, both serving and retired, who at one time or another formed part of the Hoods company, that I can do no more than ask them to accept this general acknowledgment. Their help has been of the greatest value in providing those small details, without which any portrait is no more than a lifeless mask.

E. B.

H.M.S. Hood Will Proceed

The clank of cable coming in, its heavy thump along the decks, the flicker of a dimmed torch, or the occasional glow as a blackout screen was pushed asidethese things alone showed that a fleet was getting under way.

To the whir of winches, or the Heave! onetwothreeHEAVE! of men, the last boats were being hoisted on board. Funnels rumbled and emitted, for a brief moment, a roll of oily smoke as additional sprayers were switched on to the boilers. Here and there auxiliary craft, some with mail and stores, others landing or embarking personnel, lingered alongside the darkened warships. An arrowhead of foam going past, quick and hard through the pewter-colored sea, indicated a high-speed launch, with senior officers perhaps, or last-minute dispatches. It was midnight, May 21, 1941, in Scapa Flow.

The great anchorage was dark and silent save for these few signs of activity. To the north loomed Mainland, or Pomona, largest island in the Orkneys, with its capital, Kirkwall, and its memories of the Norsementhe Temples of the Sun and Moon, and the great monolithic Stone of Odin. To the east were the quiet islands of Burray and South Ronaldsay. To the west lay Hoy with the pinnacle rock of the Old Man of Hoy standing detached from its northwest coast, guarding the entrance to the sound. Norse islandsislands destined to hold long ships ever since Harold Fairhair had added them to Norway in the ninth centurythey had been the main war base of the British fleet since Admiral Jellicoe had selected Scapa Flow in preference to Cromarty Firth in 1914.

Looking at the Flow today it is difficult to remember how many ships it held then, difficult to recall this inland sea filled with destroyers, with escort vessels coming and going, and the waters of the firths scarred by the wash of cutters and many launches. The sound of the bosuns calls no longer drowns the noise of seabirds over the headlands. In spring, though, when the islands are starred with wild flowers, and the salt sea smell is mixed with bruised grasses and herbs, it is even more hard to realize what it was like that May, eighteen years ago.

It was the long darkness when the dawn seems unimaginable. From Norway to the Atlantic coast of France an ironbound continent confronted Britain. Greece had been invaded. The battle for Crete was beginning. Everywhere the mounting losses of shipping reflected the contention that if Britian could ever be beaten, it would only be by strangling her sea lines and starving her out. The pressure was being applied now, and the screw tightened. The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen was at sea, and with her the worlds heaviest and most modern battleship, the Bismarck.

As the British ships weighed and made for the gates of Scapa Flowthe booms opening up before them and the heavy nets sliding through the waterthe men with the cold, unglamorous task of protecting the great anchorage watched them go. It was a little over a year since Lieutenant Gunther Prien had penetrated Scapa Flow in the U-47 and sunk the battleship Royal Oak. He had come through a gap in the defenses of Holm Sound, noting in his log as he did so: It is disgustingly light. The whole bay is lit up. Those weaknesses had been eliminated, but the watchers and defenders had to remember that whenever the fleet went out and the gates were open, there was always a chance of an enemy getting in.

The darkened ships slid past, silently hush-hushing through the water. The destroyers were first, moving rakish and graceful to take up their screening positions outside. Big ships were coming out too.

Dialogue varies little from one war area to another, or from one war to another for that matter.

Whats up, mate?

Some flap on. Fleets going out.

Ope no one its the gate. Last time it cost us twenty-four hours solid to fix things up.

On board the destroyers there was the inevitable grousing of small ship sailors, who tend to have the same feelings about battleships as a collie dog does about its sheep.

Always us. Only got in yesterday.

Theres a big panic on.

They spends weeks swinging round the buoy, and as soon as they goes to sea we as to go too.

They cant look after themselves.

Thisll wreck the chiefs billiards party in their second-best saloon!

Theyre both coming out.

They was always the battleships to destroyer mena sardonic they reserved for capital ships, aircraft carriers, and the remote figures of the senior officers and politicians who directed the war.

Both of them were coming outthe new Prince of Wales, and the old, the world-famous Hood. Their silhouettes were visible now against the lines of the sea and the islands: the long sweep of their foredecks, the banked ramparts of their guns, and the hunched shoulders of bridges and control towers.

We shall never see their like again, but no one who has ever watched them go by will forget the shudder that they raised along the spine. The big ships were somehow as moving as the pipes heard a long way off in the hills. There was always a kind of mist about them, a mist of sentiment and of power. Unlike aircraft, rockets, or nuclear bombs, they were a visible symbol of power allied with beautya rare combination.

Next page