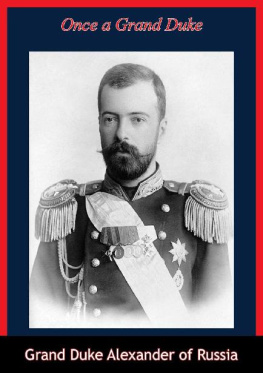

FOREWORD

THE history of the last fifty turbulent years of the Russian Empire provides only a background, but is not the subject of this book.

In compiling this record of a grand dukes progress I relied on memory only, all my letters, diaries and other documents having been partly burned by me and partly confiscated by the revolutionaries during the years of 1917 and 1918 in the Crimea.

Naturally enough, I am dealing at greater length with those who played an important part in my personal life: Emperor Alexander II, Emperor Alexander III, the last Czar Nicholas II, my mother-in-law Dowager-Empress Marie of Russia, my wife Grand Duchess Xenia, and my parents and brothers. The othersgenerals, ministers and statesmenappear to have been generously taken care of both in their own memoirs and in the numerous volumes dedicated to the Russian Revolution.

I have no desire for post-mortems and I have done my utmost to keep bias and prejudice from influencing my judgment. In fact, there is no bitterness left in my heart.

ALEXANDER, GRAND DUKE OF RUSSIA.

Paris, Autumn, 1931.

CHAPTER ONE

OUR FRIENDS OF DECEMBER THE FOURTEENTH

A TALL man of military bearing crossed the rain-drenched courtyard of the Imperial Palace in Taganrog and rapidly made for the street.

The sentinel jumped to attention, but the stranger ignored the salute. The next moment he disappeared in the dark November night that had wrapped this small southern seaport in a thick blanket of yellowish fog.

Who was it? asked the sleepy corporal of the guard, returning from his tour around the block.

I think, answered the sentinel hesitatingly, that it was His Imperial Majesty going for an early stroll.

Are you mad, man? Dont you know that His Imperial Majesty is gravely ill? The doctors gave up hope last evening and expect the end will come before dawn.

It may be so, said the sentinel, but no other man has those stooping shoulders. I guess I ought to know, having seen him daily for the last three months.

A few hours later a heavy knell filled the air for miles around, announcing that His Imperial Majesty, the Czar of all the Russias and the conqueror of NapoleonAlexander Ihad passed away in peace.

Several special couriers were dispatched immediately to notify the Government in St. Petersburg and the Heir Apparent, the brother of the late Czar, Grand Duke Constantin in Warsaw. Then a trusted officer was called in and ordered to accompany the imperial remains to the capital.

For the following ten days the entire nation breathlessly watched a pale, worn-out man crouching behind a sealed coffin and driving in a funeral coach at a speed suggestive of a raid by the French cavalry. The veterans of Austerlitz, Leipzig and Paris, stationed along the long route, shook their heads dubiously and said that it was a strange climax indeed for a reign of unsurpassed glamour and glory.

The late sovereign is not to be laid in state, said the laconic statement issued by the Government on receipt of the dispatches from Taganrog.

In vain did the foreign ambassadors and powerful courtiers try to find a plausible explanation for this mystery. Everybody pleaded ignorance and expressed bewilderment.

In the meantime something else happened which caused all eyes to be turned from the imperial mausoleum in the direction of the Plaza of the Senate. Grand Duke Constantin had abdicated in favor of his brother Nicholas. Happily married to a Polish commoner, he felt reluctant to exchange his carefree existence in Warsaw for the vicissitudes of the throne. He asked to be excused, and hoped his decision would be respected.

His letter had been read by the puzzled Senate in an atmosphere of gloomy silence.

Grand Duke Nicholashis name sounded but vaguely familiar. Of course there were four sons in the family of Czar Paul I, but who could have expected that the handsome Alexander would die without issue, and that the robust Constantin would spring such a surprise on his beloved Russia? Several years younger than his brothers, the Grand Duke Nicholas followed until December, 1825, the well-established routine of a man following a military career, and the Minister of War seemed the only official in St. Petersburg to have formed an idea of the new Czars habits and talents.

An excellent officer, a dependable executor of orders, a patient solicitor who had spent many hours of his youth waiting in the antechambers of high commanders. A likable chap of sterling qualities, but a poor boy who knew nothing of the complicated affairs of state, for he had never been invited by his brother to participate in the deliberations of the Imperial Council. Fortunately for the future of the empire, he would have to rely upon the judgment of statesmen, experienced and patriotic. This last thought brought a certain comfort into the hearts of the ministers as they went to meet the youthful ruler of Russia.

A certain coolness marked their encounter. First of all, declared the new Czar, he wanted to see with his own eyes the letter of Grand Duke Constantin. One had to be prepared for all sorts of intrigues when dealing with persons who did not belong to the army. He read it carefully and examined the signature. It still seemed unbelievable to him that an heir apparent to the Russian throne should disobey the command of the Almighty. In any event, brother Constantin should have advised the late Czar of his plans in due time, so that he, Nicholas, could have been afforded a possibility of learning le mtier dun Empereur (the profession of an Emperor).

He clenched his fists and got up. Tall, handsome and athletically built, he looked a perfect specimen of manhood.

We shall carry out the orders of our late brother and the wishes of Grand Duke Constantin, he concluded curtly, and his usage of the plural did not escape the ministers. This young man talked like a czar. It remained to be proved whether he was capable of acting as one. The occasion presented itself sooner than expected.