First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jonathan North, 2012

9781783408986

The right of Jonathan North to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including

photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt

by L S Menzies-Earl

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When,

The Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the very professional team at Pen and Sword, particularly to Rupert Harding for his unswerving support, and to the books editor, Sarah Cook.

I would also like to thank Steven H. Smith, Ned Zuparko, Alain Le Coz (for his superb work on the Fusiliers-Grenadiers), Alexander Mikaberidze, Bas de Groot, Oscar Lopez, Evan Donevich, Jack Gill, Terry Doherty, Christophe Bourachot, Thomas Hemmann, Eman Vovsi, Digby Smith, Kevin Kiley, Paul Dawson and Dominique Laude. I am also grateful to the staff at the Bibliothque nationale de France and to Chantal Prvot at the library of the Fondation Napolon in Paris.

Whenever embarking upon a prolonged period of writing and research, the support of family is crucial. I feel especially lucky in this regard, and am grateful to my parents for tolerating that episode in 1982, and to Evgenia and Alexander without whom, as the saying goes, I would have finished this in half the time.

Note on the Text

Vionnet and his contemporaries were rather cavalier about spelling. Perhaps this was inevitable when France itself was a muddle of dialects and a confusion of patois. A survey from 1794 showed that six million French citizens were completely ignorant of French, and a further six million could barely converse in the language. For instance, when a French department was created out of a part of the Austrian Netherlands, it was given the name Jemmapes, simply a misspelling of the town of Jumape (now part of Mons in Belgium). Further confusion was then caused by changing the name to Jemappes. So perhaps it is understandable that if our protagonists could hardly agree on how to spell the names of French towns, then they would find it hard to agree on how to write those of remote villages in western Lithuania.

I have tried to use the place names generally agreed upon in the early nineteenth century so that this text can be read with and against other memoirs. So I have opted for Vilna, but adding the modern name Vilnius on first instance, rather than Wilna or Wilno. It has not always been possible to identify some locations, especially those in eastern Prussia or Silesia (territories which became Polish or Russian after 1945).

Similar problems bedevil individuals mentioned in the text. Vionnet is relatively good at accurately citing his comrades, but Sergeant Bourgogne, who fought in the same unit, is less reliable (possibly because he wrote his memoirs from memory while a prisoner of war). So Bourgogne cites Sergeant Leboude or Sergeant Oudicte when he means Jean-Franois-Nicolas Leboutte or Sergeant-Major Nicolas Oudiette. Bourgogne is an interesting example. He did at least get Lieutenant Serrariss name right, but his English translator muddled it into the beautiful but incorrect Lieutenant Cesarisse, something which also happened to Joseph Vachin (who inexplicably became Captain Vachain).

All translations are my own. I have been fortunate to have had available both editions of Vionnets text (the 1899 edition and the 1913 edition). The earlier edition includes some text from the very opening of the Russian campaign, which the 1913 edition omits, but both conclude at the same point in time. I have preferred to translate Bourgognes memoirs from the French, not only because of the reasons stated above, but also because the English edition misses out some important details and omits entire paragraphs that can be found in the French text.

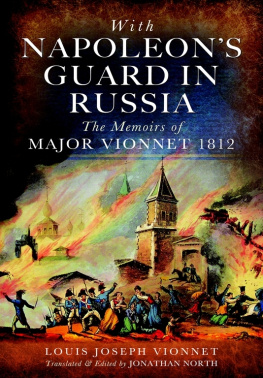

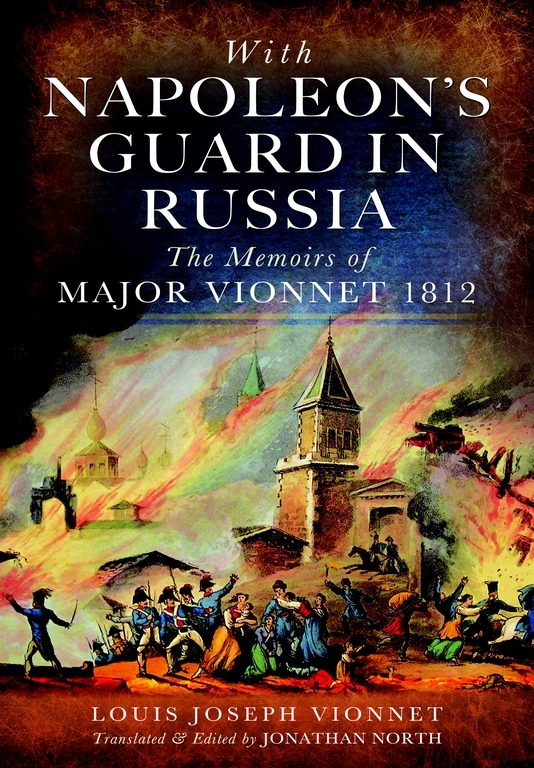

This book is very much the story of Major Vionnet, of his comrades in arms and of the regiment in which he so proudly fought. It focuses on the 1812 campaign in Russia, and on the disaster that befell Napoleons armies in that terrible year. Vionnets own account of the debacle is supplemented by accounts of those who fought alongside him. Perhaps because Vionnets unit, the Fusiliers-Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard, insisted on recruiting amongst the literate, we have been fortunate enough to be able to make use of surviving texts by Lieutenant Serraris, Lieutenant Vachin, Sergeant Bourgogne, Sergeant Scheltens, Corporal Michaud and, for early 1813, Surgeon Lagneau. I have also added in some text from the man who commanded Vionnets division, the rather unsympathetic General Roguet. All these men served with this regiment, and their accounts supplement or confirm Vionnets own account. It makes for a useful corroboration of facts, and can sometimes prove amusing. For example, we have Vionnet and Roguet fulminating against pillagers and looters (blaming foreigners, or thieves), while their NCOs cheerfully describe how much pillaging they have been doing, how much money they have accrued and what supplies they have obtained (to share occasionally with their officers).

I have, it might seem arbitrarily, concluded Vionnets account after he was wounded in 1813, a few months after he was transferred out of the Fusiliers-Grenadiers. It seemed a logical point at which to curtail the story of the Russian campaign, and it goes to show that few of those who survived that catastrophe remained unscathed in the disaster in Germany in 1813.

Introduction

Vionnet and his Regiment

Napoleons Imperial Guard was a vital part of the armies that conquered much of Europe. It was an organisation on which he lavished a sustained degree of meticulous Napoleonic attention, from matters of personnel, dress, deportment and pay, to deployment on the battlefield.

The Guard had originated from bodies of reliable troops hand-picked to guard the National Assembly in 1789, to offset the gathering storms in a turbulent Paris. By late 1795, after various changes of name, purges and reorganisations, a unit of horse and foot named the Garde du Directoire emerged to protect the Directory as it went about its business. It was composed of veterans, formed into infantry (not yet sporting the famous bearskins) and cavalry (chiefly based on personnel from the 3rd Dragoons) and had a band of brilliant musicians attached. Napoleons coup in November 1799 allowed him a free hand to fashion his own household troops. Using the Garde du Directoire as a base, he merged it with other guard units, filled it with loyal supporters and expanded it to become two battalions of Grenadiers (now in tall bearskins) and a company of Chasseurs Pied, as well as some mounted chasseurs (Chasseurs Cheval) and a squadron of mounted Grenadiers. Some artillery was also attached. From this nucleus the Guard began to grow and to establish itself as an army within an army, especially when Napoleon proclaimed himself Consul for life and gave himself a free hand to do as he pleased in all matters of state. He sought to place reliable veterans in the Guard, literate men no younger than twenty-five years of age who had already served in three campaigns (ideally including those led by Napoleon himself). In return the men enjoyed enhanced status and enhanced pay (450 francs a year for a Grenadier). In 1800, as Napoleon sought to sweep the Allies once more from the plains of Italy, the Guard earned its preferential treatment by playing an important part in the victory at Marengo, and paid for it with heavy losses. It was then to be increased still further in November 1801, recruiting men from the line (now required to have served in four campaigns) who were at least 1.80 metres tall if they wanted to be a Grenadier or 1.70 metres if they wished to become a Chasseur.