CONTENTS

Introduction

In April 1814, Napoleon wanted to die. Paris had fallen to the Allies and so, believing there was no other option but suicide, the French emperor swallowed the poison he had worn around his neck since nearly being captured by the Russians during the retreat from Moscow two years earlier. In the event the poison failed, and the emperor was exiled to Elba, only to return in a last effort to wrest back his throne during the Hundred Days in 1815.

An unsigned portrait of Napoleon I (17691821), c. 1812. The French emperors Imperial Guard would save his field army at Krasnyi and provide its principal striking force in the campaigns of 1813 and 1814. Devotion to the person of the emperor came under increasing pressure as the wars went against France after 1812, but remained a potent motivation for Napoleons Guardsmen until the end. (RC)

It was a far cry from those days when the young Bonaparte had saved the French Revolution and was made First Consul and then emperor. Magnificent victories followed Austerlitz, Jena and Auerstdt, Friedland and Wagram which made Napoleon the master of Europe. In 1812 there had been an air of anticipation that Napoleon would once again be victorious, this time against Russia. In his memoirs, Sous-lieutenant Paul de Bourgoing of the 5th Tirailleurs recalled his feelings on the eve of the campaign:

You can not imagine the enthusiasm with which the young men prepared for this distant expedition. I was nineteen at the time and we were so confident of success that, thinking of our ambition and chances of promotion, we regarded this campaign, with regret, as the time that the Emperor would have to try his luck in battle in order to conquer the world. (Quoted in Uffindell 2007: 77)

There was also excitement in Russia. Among those watching the Russian soldiers marching to the frontier was 13-year-old Alexander Pushkin, the future poet, who attended school near St Petersburg:

To begin with we saluted all the regiments of the Guard which marched through Tsarskoe-Selo. We were always there as soon as they came in sight, and we even went out to meet them during lessons. We accompanied them with a fervent prayer, we kissed our relations and friends, and grenadiers wearing heavy moustaches blessed us with a sign of the cross without leaving the ranks. How many tears we shed! (Quoted in Spring 2009: 18)

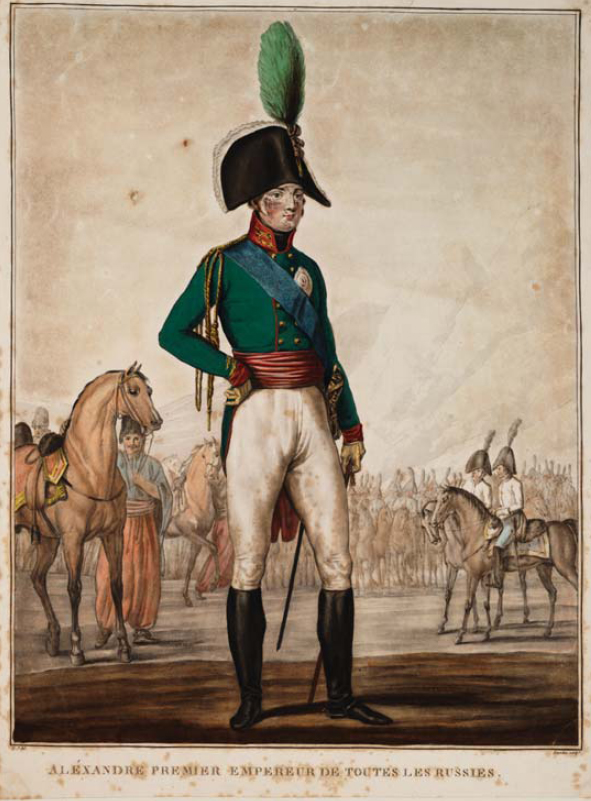

Tsar Alexander I (17771825), by Charles Franois Gabriel Levachez, c. 181314. Initially somewhat impressed by the French ruler, Alexander was by 1812 determined to crush Napoleon and was at the centre of the coalition effort to defeat France in 181214. (ASKB)

Many of Tsar Alexanders officers wanted their ruler to order an invasion of the Duchy of Warsaw, Napoleons Polish satellite state, and then Germany, but in the end when war did come it would be a defensive campaign for the Russians. The Russians initial retreat towards Moscow would be followed by their dogged pursuit of the Grande Arme to the borders of Russias empire and beyond, and ultimately to the gates of Paris in the spring of 1814.

The regiments of Napoleons Imperial Guard and Russias Jaeger light infantry arm would be at the centre of these campaigns for supremacy in Europe. In 1809 Napoleon had increased the size of his Imperial Guard, dividing it into the Old, Middle and Young Guard, and would continue to raise new regiments for his Young Guard almost up to his abdication. For many years the men of the Imperial Guard were looked upon with resentment and envy by the rest of the French Army, since they were given preferential treatment. By the end of the 1814 campaign the regiments of the Young Guard were on paper an immense elite formation, but in reality the regiments were hastily trained, poorly equipped and so under-strength that they mustered little more than weak battalions, and battalions were just companies.

Of course any regiment on either side could act as skirmishers if required, but the benefits of open-order tactics were not lost on Tsar Alexander or his generals. During the French Revolutionary Wars and the early campaigns of the 19th century the Russian Jaeger were no match for their French counterparts, but by 1812 they had gained valuable experience in the art of light-infantry warfare and became the equals of the French, if not better. Seeing their usefulness, the Tsar converted musketeer regiments into Jaeger units, as well as raising new ones. Within the Russian Lifeguard, Alexander expanded the Jaeger battalion to regimental strength and raised the Finland Guards Regiment, which was designated, dressed and equipped as a light-infantry regiment. Unlike Napoleon, Alexander channelled virtually all his fresh manpower into existing regiments; this meant that the veterans were able to train the new recruits, and so the fighting capabilities of the regiments were preserved and enhanced.

Soldiers of the 41st Jaeger Regiment in May 1815, drawn by Johann Adam Klein and coloured by Georg Schfer. This regiment served with the 12th Infantry Division alongside the 6th Jaeger Regiment; the light-blue shoulder-straps visible here indicate the junior Jaeger regiment of the Division. The grenadier company junior officer shown here wears grey overalls, gorget, unfringed epaulettes, waist-sash and knapsack, but retains an NCOs shako pompon quartered in white and mixed black and orange. The grenadier company NCO to his left wears a white-tipped plume and lace edging to his cuffs and collar; this edging should be gold, not white. (ASKB)

In the three battles examined here, which stretch over the last years of the Napoleonic Wars, the decline of the Young Guard and the rise of the Russian Jaeger arm are starkly exposed. I have chosen to focus on the battlefield performance of three of Napoleons Voltigeur regiments the 1st, 2nd and 14th and that of the two Lifeguard Jaeger units, together with the 19th Jaeger Regiment, a unit that benefitted greatly from its extensive experience of warfare against the Ottomans and others before it joined the fight against Napoleon. Although Napoleons tirailleur regiments also saw widespread combat against Alexanders forces, the sources consulted in the preparation of this book favoured the voltigeurs, and their experiences and performance are in any event likely to have been very similar to those of their tirailleur brethren. Similarly, the longevity and high profile of the two Jaeger regiments of Alexanders Lifeguard meant that it was possible to form a much more detailed picture of their combat performance than it would have been to do so for many of the Line Jaeger regiments.

A Flanquer-grenadier of the Imperial Guard, after Carle Vernet. Uniformed, like their colleagues in the Flanquers-chasseurs, in green with yellow piping rather than the blue worn by the bulk of the Young Guard infantry, the Flanquers-grenadiers were formed in 1813; unusually, they wore shako-cords, which were officially suppressed for the Tirailleurs and Voltigeurs in that year, and yellow lace edging on their gaiters. The single cross-belt, lack of sabre and lapels closed to the waist are characteristic of the appearance of the Young Guard after April 1813. (RC)