This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING www.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books contact@picklepartnerspublishing.com

Text originally published in 1918 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

A SCHOLARS LETTERS

FROM THE FRONT

WRITTEN BY

STEPHEN H. HEWETT

2ND LIEUT. IN THE ROYAL WARWICKSHIRE REGIMENT

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

F. F. URQUHART

FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD

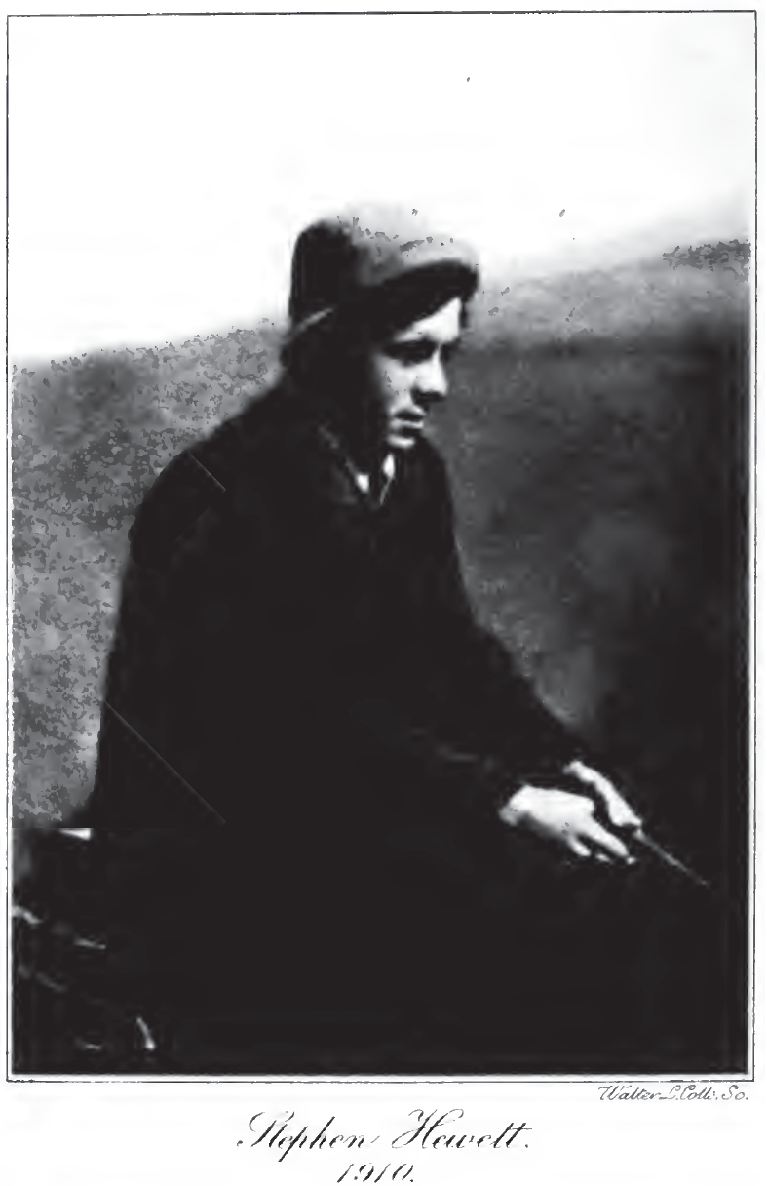

WITH PORTRAIT

INTRODUCTION

MANY soldiers letters have been published during the past three years, and with reason, for we should keep what record we can of a generation so gallant and so sorely stricken. Yet a few words of explanation are perhaps due, when an addition is made to the number of such publications. Englishmen are proverbially reticent in expression, especially when they feel deeply, and the letters of English soldiers have been distinguished on the whole by this reserve. They contain, often enough, vivid pictures of things done or suffered, of the daily routine or the occasional adventure, but they are rarely meditative, they rarely reveal the thoughts or emotions of the writer, and we must go to their verses to find what our soldiers feel about the war. There is therefore good reason for publishing some of the letters of a young Oxford scholar to whom the war was a searching experience but who took it with a cheerful heart, one who from boyhood had sought the art of expression and for whom a thought was not mature until it had received adequate utterance.

Stephen Hewett was born in India in 1893. His father was in the Indian telegraph service, a career which in the wilder parts of the country had often meant danger and adventure. On Mr. Hewetts retirement from the service the family came to live in Exeter, and Stephen was sent to Downside in 1905. He remained there till midsummer 1911. The school lies on the northern slopes of the Mendips, in an open, windy country of grass and trees, of distant views and unexpected valleys. It is under the care of Benedictine monks and no boy of any sensitiveness could fail to be influenced, however unconsciously, by the orderly carrying out of the Catholic liturgy in a church worthy of it, while the trials of school life are softened by the share which the boys have in the peace and sympathy of the Benedictine family. As a boy Stephen Hewett was very reserved, not making friends easily, and very diffident of his powers. Yet his capacity was undoubted from the first. He read widely, thoughtfully and with intense appreciation. With this power of assimilation he combined a very mature taste and a delight in the music and meaning of single lines, of phrases which seemed to him the perfect expression of a thought or an emotion. He went up for the Balliol Scholarship Examination at the age of sixteen and won an Exhibition. He went up again in the following year, 1910, and was elected to the first scholarship. But he was far from being only a scholar. He was a good cricketer with some excellent strokes, which are still remembered in the school, and in his last year he was captain of the XI. He played also in the football and hockey teams. That great period in a boys life, his last year at school, he enjoyed to the full. In the secure possession of a scholarship and under sympathetic guidance he could read what he wished; while with success and maturer years there came greater self-confidence. Shy, hitherto, and amusingly old-fashioned and deferential in manner, he came to revel in talk with a few friends, especially with those older than himself. In public he was still diffident, and this although he was captain of the school and could play with success the part of the Duke in the Gondoliers.

Stephen Hewetts devotion to Downside never wavered even for a moment during the five years that he had yet to live, as indeed his letters will show. He loved its fine bracing air, its spacious viewsthat, for instance, from Masbury Camp towards Glastonbury Tor across to the distant Quantocksfor he was a passionate Wordsworthian, and the hills and fields and trees, especially the hills, gave him such delight that he was not merely using a strong expression when he spoke of being maddened by a view. During these years the passage that he quotes most frequently was a line from Victor Hugo,

Le vent qui vient travers la montagne

Me rendra fou.

In the little world of Downside he had a number of friends, both among the lay masters and among the monks, while bis receptive nature, sensitive to every impression, found support in a society which is set in due order and reason, as little of the world outside is nowadays, where God is the public and acknowledged sovereign of daily life, and where religion is not an occasional duty but a constant inspiration. If he had lived through the war he would almost certainly have returned to join the Downside monks, and he always considered that his future profession was to be that of a teacher.

It would be difficult to imagine a boy more likely to enjoy Oxford. His scholarly instincts and wide reading, his interests in questions of art and literature, his craving for friendship and for friendly talks on all the subjects that were so alive to him, they would all find a response in Oxford. His diffidence, it is true, was against him, and when he came to Balliol in October, 1911, it was some little time before he found his level. Indeed, he always disliked any kind of public appearance, and he never was what is called a leading man in college. In some things he was unable to overcome his old nervousness: though quite a success at cricket he gave up the game because he found that the prospect even of a college match made him too excited to do his work. Hockey he played with much more confidence, and so well that he got into the University team and distinguished himself in the match against Cambridge in 1914. Much, however, as he enjoyed his hockey, Stephen Hewetts real interests were naturally elsewhere. They were, for one thing, with his work as a scholar, in which he was uniformly successful, winning all the possible University scholarships, the Craven, the Hertford, and the Ireland: and he had indeed a constant delight in the great classics. His vacation rambles and visits to Italy or the Alps were sources of intense pleasure, but he always returned with renewed affection to the Haldons, the hills near his home where one can lie on the hills in absolute quiet and watch the sea. His home and his family were never far from his thoughts. But most of all he delighted at Oxford in the society of his friends, young men with whom he would discuss his and their thoughts about art, literature and the thousand and one things which crowd into the mind of a young man so gifted. Before he went to Oxford he was afraid of its pleasures, and in one of these letters looking back to his Balliol days he writes of the lotus-eating element that was too much for us in the Oxford days. But in this he was probably over-severe with himself. His time at the University was well employed. His ideal of work was a high one and he had repeatedly, for reasons of health, to allow himself periods of comparative rest. That he enjoyed his life so intensely was not due to self-indulgence, it was simply the result of his natural power of enjoying the best things. For Stephen Hewetts greatest gift, as we knew him, was this extraordinary capacity for appreciation. A University atmosphere is naturally, perhaps, critical, but Stephens power was one of praise, not, of course, the mere praise of the lips, but the praise of intense enjoyment and gratitude. Nature, the books he read, in all their varied kinds, his friends, they were all a source of constant delight. So receptive was his mind, so appreciative, that his friends may have asked themselves whether he was not wanting in speculative and critical power, in originality. Those who worked with him knew that this was not the case, and one of his tutors writes of his work as a classical scholar: In all that he wrote, and especially in his essays, nothing was more remarkable than the degree to which his work was his own. He read books about the Classics, of course, but he rarely, if ever, repeated any judgment about Ancient Literature or Art unless he had understood it and accepted it as his own. His own judgments were formed with unusual care and conscientiousness, and in consequence of this, and of his natural gifts of insight and appreciation, they were often much truer and deeper than those which are to be found, oft-repeated, in books. His style also was careful, without being in any way affected; he had a real genius for expression at once adequate and impressive, and often humorous; and any class of which he was a member must have learned, consciously and unconsciously, much more from him than from its nominal teacher. Certainly it is unusual for an essay class to show real disappointment at the absence of one of their number who is in the habit of writing at considerable length; and such disappointment was both felt and expressed when circumstances kept him away. His reading of his essays was worthy of their matterunaffected, but expressive and musical, and very good to listen to. In the more technical parts of his workin composition and translationhe showed great cleverness as well as the fine taste and the singular maturity which were characteristic of his essays. He rarely, if ever, wrote Latin or Greek which was in no particular style, and many of his compositions could be published as models with scarcely a word altered. Criticism, indeed, or at least selection, he had practised instinctively from early days in his exclusion of what was sordid or evil, and literary discussion came to take a great part in his talk and letters; his Greats work during his last year at Oxford showed that he had real philosophical capacity, though it was perhaps in speculation about art, in the widest sense of the term, that he took most personal interest. He once summarised his practical philosophy in a letter written in less happy days to one of his sisters: Never let your memories be spoilt by pain. The joys of memory are certain and inalienable which no man shall take from you. They go at once to join the number of things which are flawlessly delightful in the region where art lives. Outside that region nothing is of value except friendships externally and character within. Not circumstance: that counts for nothing.... This is the lesson I have set myself to learn.