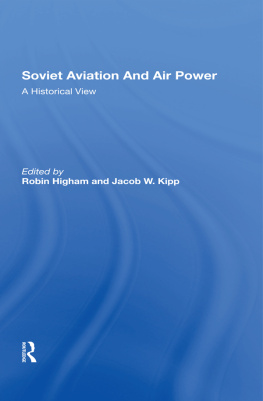

About the Book and Author

This comprehensive examination of Soviet air power analyzes not only the three branches of the USSR Military Air Forces (VVS)Frontal Aviation, Long-Range Aviation, and Military Air Transportbut also Naval Aviation and the National Air Defense. Dr. Whiting starts with the history of Soviet air power, emphasizing World War II and postwar developments and concluding that the Soviets have been far more inclined than the U.S. military to draw lessons from World War II experiences. He then describes how aviation fits into the overall Soviet military organization. Subsequent chapters deal in depth with the three VVS components, Naval Aviation, and the National Air Defense, and with the role of aviation in the projection of Soviet power outside the Soviet bloc. Dr. Whiting traces Soviet efforts to influence and control client states since the mid-1950s through the export of military weapons and advisers. Throughout the book and particularly in the concluding chapter, attention is given to the exponential increase in Soviet air power over the last fifteen years. The author deals with the quantitative improvement in striking power made possible by close integration of air and ground forces and with the radical changes in organization and doctrine that have accompanied it. Not only can air assets be shifted from place to place in massive numbers with utmost speed, but lost or damaged aircraft can be readily replaced because of a huge reservoir maintained by the Soviets. In the interest of achieving air superiority over both NATO and Chinese forces, Soviet power projection has come of age.

Kenneth R. Whiting was chief of the Documentary Research Division, Air University, from 1951-1985. He is the author of The Soviet Union Today.

First published 1986 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1986 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Whiting, Kenneth R.

Soviet air power.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Aeronautics, MilitarySoviet Union. I. Title.

UG635.S65W46 1986 358.4'00947 85-52423

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-28811-2 (hbk)

Any attempt to describe in a short format how the Soviets built an air force and how they used it over the last six and a half decades is bound to be thin and spotty. Since access to Soviet archives is not possible for Western researchers, thus precluding scholarly activities in documentary collections, the story must perforce be derived largely from secondary materials. With all its limitations, however, the story should be of interest to many Americans since it concerns the infancy, adolescence, and present maturity of the only source of air power comparable to that of the United States.

When the Bolsheviks came to power in November 1917, they inherited a higgledy-piggledy tsarist air force made up of obsolescent foreign-type aircraft, either imported or manufactured in Russia under license. The one exception was Sikorsky's Il'ya Muromets, the largest bomber and only successful four-engine plane of that time. Air power was a negligible factor in the Civil War between the Reds and the Whites (1918-21) as aircraft were scarce, the little fuel available was unbelievably awful, and the combat theaters were enormous. Airplanes did, however, play havoc with cavalry since they could locate them easily from the air and were effective in low-level attacks.

During the New Economic Policy (NEP) era (1921-28), the Red Army as a whole and the air force in particular developed slowly and erratically. It simply could not get the modern weapons needed for a first-class army. Probably the most fruitful input in that period as far as the air force was concerned was its close connection with the German Wehrmacht. Then came Joseph Stalin's decision to industrialize the Soviet Union at a forced tempo and with a very heavy bias toward the military-industrial complex. It then became possible to build an indigenous aircraft industry to turn out Soviet-built airplanes.

Stalin's new "Falcons" tried out their aircraft and their skills in Spain, in the Sino-Japanese War, and even more directly against the Japanese at Lake Khasan in 1938 and Khalkhin-Gol in 1939. In the Winter War of 1939-40, the performance of the Soviet Air Force, like that of the Red Army in general was miserable, which understates the case. Unfortunately for the Russians, much of the expertise acquired in the conflicts of the 1930s was liquidated by Stalin in the purge of the military in 1937-40, a slaughter that cost the Soviet armed forces some 80 percent of its top officers.

The Great Patriotic War was the iron test for Soviet air power, and it nearly flunked the trial when the Luftwaffe caught thousands of Soviet aircraft on the ground in the early period of the war. The Soviets were able, however, to move much of their aviation industry beyond the Urals and into Central Asia during the summer and fall of 1941, thus safely beyond the range of Nazi bombers. By early 1942 the planes were coming off the production lines in ever-increasing numbers. Inasmuch as most of the Soviet aircraft losses in the early months of the war were on the ground, there were plenty of pilots around to fly the new planes. The Soviet airmen made a good showing in the defense of Moscow at the end of 1941 and put on a still better show against the Luftwaffe in the battle of Stalingrad in 1942-43. By the middle of 1943, when it crushed the German offensive at Kursk, the Soviet Air Force was in the ascendancy and by 1944 was drowning the Luftwaffe in a flood of Soviet aircraft. The prodigious output of the Russian aviation industry was the main element in the victorious outcome in the air war.

Russia emerged from the war with an enormous array of ground forces and a plentitude of close support aircraft, but it faced what was perceived as a potentially hostile United States replete with a strategic air force and a monopoly on the atomic bomb as well as control of the seas. It was not surprising that Stalin went all out to obtain the twin necessities needed to cope with the threat: the atomic bomb and an adequate air defenseinterceptors, radar, and better antiaircraft artillery. The air defense got its baptism in the Korean conflict, but the newly acquired atomic weapons needed delivery vehicles of intercontinental range. By 1954-55, the Soviets had two long-range bombers (the Tu-95 Bear and the Mya-4 Bison) as well as a medium-range Tu-16 Badger. Although these strategic bombers were not in the same league as the best American planes, they did provide a psychological lift for Soviet morale until the advent of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in 1957.

Nikita Khrushchev's rise to power in the late 1950s coincided with the coming of the ICBM, which overly impressed him and caused him to push out beyond the limits of the Soviet empire and undertake injudicious gambits all over the globe. Trying to do too much with too little, he had his bluff called in the most humiliating manner in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.