To Read My Heart

The Journal of Rachel Van Dyke, 18101811

Edited by

Lucia McMahon and Deborah Schriver

Copyright 2000 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Van Dyke, Rachel, b. 1793.

To read my heart : the journal of Rachel Van Dyke, 18101811 / edited by Lucia McMahon and Deborah Schriver.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8122-3549-5 (acid-free paper)

1. Van Dyke, Rachel, b. 1793Diaries. 2. New Brunswick (N.J.)Biography. 3. Young womenNew JerseyNew BrunswickDiaries. 4. Young womenNew JerseyNew BrunswickSocial life and customs19th century. 5. New Brunswick (N.J.)Social life and customs19th century. 6. New Brunswick (N.J.)Intellectual life19th century. I. McMahon, Lucia. II. Schriver, Deborah. III. Title.

F144.N5 V36 2000

974.942092dc21

[B]

99-089832

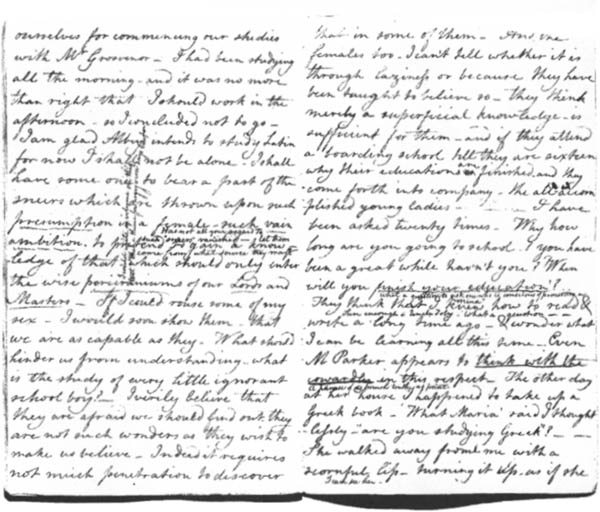

Frontispiece: June 20, 1810, journal entry with marginal notes written by Ebenezer Grosvenor to Rachel Van Dyke. Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

Contents

Deborah Schriver

Lucia McMahon

Editorial Note

The original journal of Rachel Van Dyke is held at Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries. It consists of twenty-three numbered fascicles, each approximately 4 X 6 inches in size and approximately 40 to 48 pages in length. Each book has a front and back cover, which is numbered and dated. The first of these books has not been located, and thus our transcription of the journal begins with Rachels . We have retained Rachels numbering of the journal books.

The journal presented a number of editing challenges: spelling and punctuation were at times irregular and inconsistent; many persons were referred to by initials or first names only; in several places, text has been crossed or cut from the manuscript. In addition, several fascicles contain the handwriting and marginalia of Ebenezer Grosvenor, Rachels teacher and friend, with whom she exchanged journals on several occasions.

In preparing the manuscript for publication, the editors have presented the journal as closely as possible to the original, with a few exceptions designed to assist the reader. Rachel frequently used dashes rather than periods at the end of sentences, and we have replaced these dashes with periods, except when the dashes seem critical to the tone of the text. We have corrected Rachels inconsistencies of spelling for certain words (e.g. stoping to stopping; tryed to tried), except in instances where Ebenezer Grosvenor read and marked the misspelling in Rachels journal (his marks are retained in the transcription). At moments that appear to be slips of the pen, we have silently corrected spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. Words that seem to have been left out or that appear partially written have been inserted in square brackets for clarity.

Whenever possible, we have identified in brackets the full names of persons that Rachel mentioned by initials or first name. There is, however, one notable exception. Throughout her journal, Rachel consistently referred to Ebenezer Grosvenor as Mr. G- and we have not altered this reference. After careful review, the editors feel this reference retains Rachels voice and is essential to preserving the tone and nature of the journal. While to some readers it may suggest an inequity in their relationship, the editors believe that Rachel used the designation with a mixture of respect and affection, to indicate that Mr. G- was both her teacher and friend.

Where the original manuscript contains crossed-out text or torn pages, we have indicated the break in the text flow with bracketed ellipses [... ] and provided a note explaining the interruption.

For the presence of marginalia, written by both Rachel and Mr. G-, the editors have designed a set of editorial guides and references to assist the reader in following the conversations that took place between the lines and across the pages of the journal. For each journal book that was read by Mr. G-, we have provided a note at the beginning of the chapter indicating the date(s) of the exchange, indicating the date Mr. G-s marginalia were added. Mr. G-s marginal notes are transcribed as closely to their original location as possible and are indicated by bold italics type and identified by [G]. Notes that were added by Rachel at a later date, often in direct response to Mr. G-s comments, are in bold type and identified by [R]. Where appropriate, the editors have also provided notes to indicate marginalia that were difficult to transcribe, including the use of wavy lines, bracketed text, and the like. Text underlined by Rachel in the original manuscript appears in italics here. Underlining in this volume signifies Mr. G-s marks. Strikethrough appears in the text as found in the original manuscript, and is usually followed by an explanatory note.

We have identified as many of Rachels literary references as possible, and full citations appear in the notes. If no note follows a literary work, we have not been able to determine its full reference.

Introduction

Deborah Schriver

To Read My Heart: The Journal of Rachel Van Dyke, 18101811 offers a daily journal written by a seventeen-year-old student and resident of New Brunswick, New Jersey. Two significant events in Rachels life, her final day at a female academy in May 1810 and the death of her father in June 1811, frame the journal. Entries reveal views of early nineteenth-century New Jersey life and opinions on social customs, marriage, gender roles, friendship, and religion. An avid reader and dedicated student, Rachel discusses her insights into literature, Biblical teachings, poetry, science, and philosophy. Her commentaries reflect the culture of the time and have special value as the expression of a nineteenth-century young woman seeking to understand her own role as an emerging adult. The significant outcome is a first-person narrative rich in emotionality, offering a young womans view of historical and cultural development of the early nineteenth century.

Though Rachels own intention was to improve myself in compositionto practise expressing my sentiments through daily practice, her journal serves a greater purpose as a valuable historical, cultural, and literary document (May 21, 1810). Historically, Rachels journal provides a special perspective on New Brunswick during the years of growth for Rutgers University (Queens College) and the Dutch Reformed Church. A number of well-known figures are mentioned throughout the journal, including Dr. Ira Condict, the Frelinghuysen family, Dr. John H. Livingston, and Dr. Benjamin Rush. Rachels daily accounts provide a valuable picture of social customs, daily hardships, and current events of early nineteenth-century life in New Brunswick. The journal presents the rare opportunity to experience this period through the personal perspective of a young woman as she contemplates her own significant place in society.