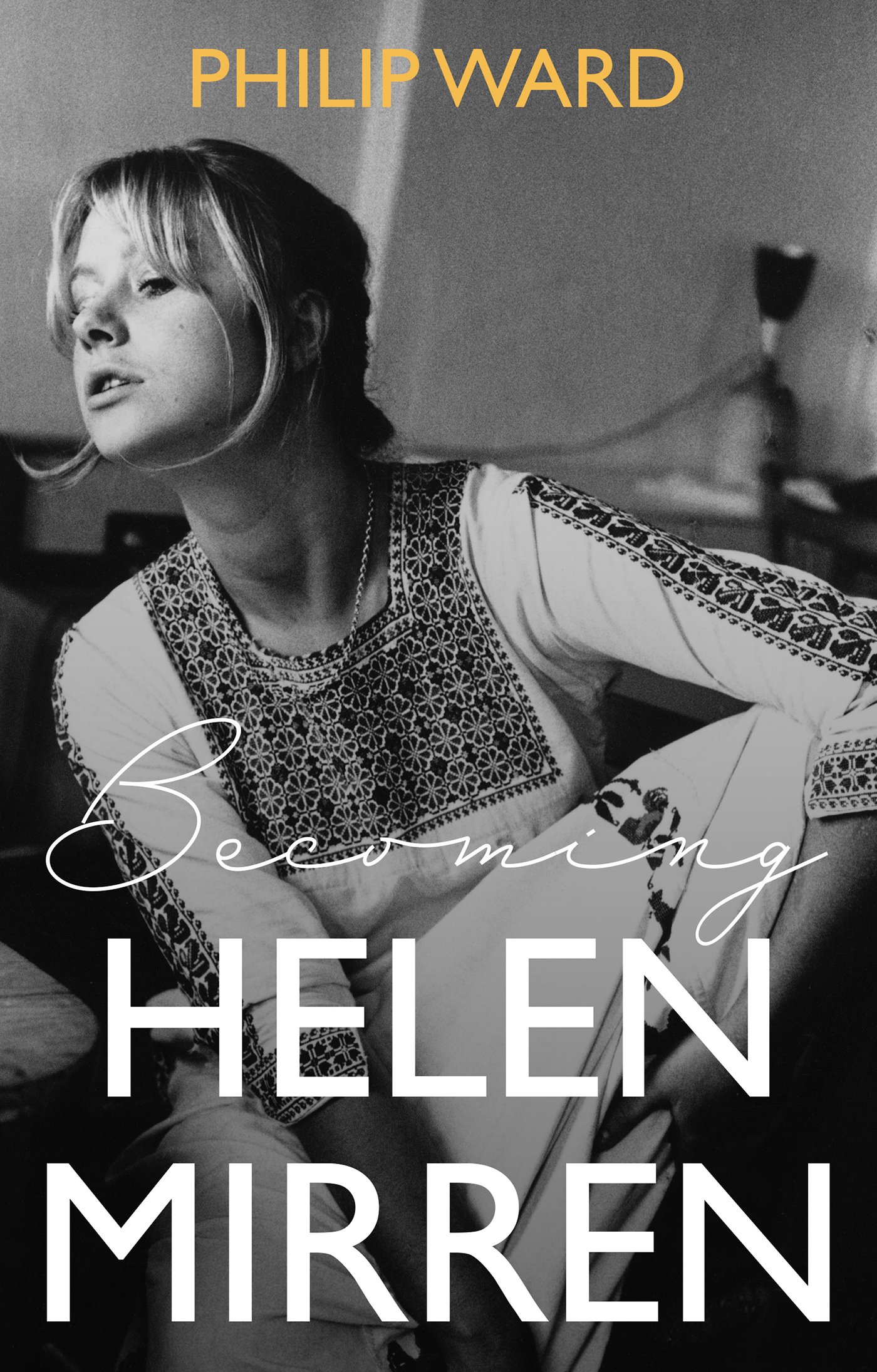

BECOMING HELEN MIRREN

Philip Ward

Copyright 2019 Philip Ward

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1838597 146

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Front cover: Helen Mirren at her flat in Kennington, South London, 1969 ( photo Neil Libbert)

SAINSBURY | In other words, its become of us. |

HEADINGLEY | Become of us? |

SAINSBURY | Didnt you ever wonder what would become of you? |

TATE | Yes, but what has become of us? |

SAINSBURY | Heaven knows. But whatever it is, become of us it has. |

Michael Frayn, Donkeys Years (1976) |

Between 18 and 30 were the worst years of my life Odd, isnt it, when you consider that, at the time, youre at your physical best? In reality, there is all the misery and fear of wondering what is to become of you.

Helen Mirren (b. 1945), quoted in The Times (1996)

INTRODUCTION

Today she is an international star, an Academy Award winner and recipient of multiple Golden Globes. But before Prime Suspect made her a household name on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1990s, Helen Mirren had already had a distinguished career, primarily as a stage actress, in her native Britain. This book sets out to explore that early career, so much less well known to her worldwide fans, suggesting how a series of decisive and original performances of classic and modern work in her twenties and thirties laid the foundations for the later movie roles that elevated her to Hollywood royalty.

So much of whats written about her now, especially on the internet, comes from the other side of the pond, from Americans who came to her late, in the Nineties through Prime Suspect (which was aired on PBS in the States to great acclaim), or later still, when she scooped the Oscar for The Queen . They view her career backwards from that point. My perspective is the exact opposite. I discovered her early in her career, when she was known as a theatre and TV actress, and that only in Britain; her film roles at that time were confined to small parts in big films ( O Lucky Man! ) or big parts in small but eminently forgettable ones ( Hussy ).

The emphasis will be on her early work, to about 1983, hence the title Becoming Helen Mirren. I go back to that time, not just because my most vivid memories of her are the earliest, not just because back in the day she was kind enough to answer the self-obsessed scribblings of an adolescent fan, but because I feel no one quite knew not least Mirren herself what she would become in the next thirty years. Who in 1974 would have confidently predicted that this one-time self-declared Trotskyite would end up a Dame of the British Empire and a global brand so recognisable that she has only to step out in a bikini or utter an expletive in a daytime TV interview for the Twittersphere to go into meltdown?

Well, perhaps there was one person who foresaw all. In her autobiography, Mirren describes visiting a palm-reader in a back street of Golders Green. This would have been about 1968. He was an Indian man, more like an accountant than a mystic, she recalls. He told her that shed be successful in life but would see her greatest success later, after the age of 45: Not something you want to hear at the age of 23 I realised that I did not want to know what the future held. I wanted my life to be an adventure. The paradox is that this adventure has taken her to a future she appeared to disdain when she was young: a life atop the Tinseltown glitterati .

As a student working as an usherette at the Everyman Cinema, Hampstead, in the mid-Sixties, she watched her idols Monica Vitti and Anna Magnani on the big screen: European Art Cinema writ large. This, she told a group of film students in 2017, was the future she dreamt for herself. The success she enjoys now as a movie star in the American industry is both a fulfilment and (in my heretical view) a falling-short. Looking back, I see that it is my adolescent self circa 1975 who projected an alternative future for her as theatrical grande dame , then fell to grumbling and lost interest because she departed to Hollywood. If I write nothing about her work after the early 1980s, it is because that is when my interest flagged, not because she ceased doing valuable work after that time. Its the becoming that captivates me, not the become. Essentially, her career falls into two halves, with a caesura somewhere in the Eighties. The fortune-teller in a Golders Green back street predicted shed have her greatest success after the age of 45, and so it was after 1990.

My selection is highly partial. The list of other work at the end of this book shows how much in demand she was as a young actress, and it will be obvious that Ive omitted to discuss some celebrated early roles. Perhaps Ill return to them in a follow-up volume. For now, I concentrate on the performances or media appearances that caught my attention as someone, over a decade younger than her, who was himself in process of becoming: in my case, a work still in progress.

I remain, too, the prisoner of memory. My problem, at this distance, in recalling theatrical moments is to distinguish between real memories and false ones what I know happened and what I think happened (but maybe didnt). Kenneth Tynan, doyen of theatre critics, wrote of how he was deeply seduced by the challenge of perpetuating in print what he had seen on stage: it seemed to me unfair that an art so potent should also be so transient, he reflected. With apologies for sometimes riffing on matters better left to literary criticism, I commit here to the page my own fleeting moments. For example, on 27 April 1978 I was perched high in the gods at the Aldwych Theatre, then London home to the Royal Shakespeare Company. The play was Henry VI Part 2 , with Alan Howard as the enfeebled king and Helen Mirren his embattled queen, the she-wolf Margaret of Anjou. Suddenly, from stage left entered a shabbily dressed man in long overcoat. He held a bunch of daffodils, which he presented to Mirren before exiting as mysteriously as he had come. Was it planned? Apparently not. It seems the gatecrasher may have wandered in unchallenged from the Peabody Buildings next door, a refuge for rough sleepers. Alan Howard recalls the same one-off incident, only in his version the daffodil-man walks to the mound on which king and queen are seated, lays his flowers down, and nods to the actors; they nod in acknowledgement, he turns and leaves the stage without speaking. For Howard, the mans unexpected arrival onstage felt appropriate, right, miraculous it took the scene where it needed to be, to a territory beyond despair. It was a Beckett moment in a Shakespeare play. In my recollection it has become an act of homage to my then favourite actress, a wish-fulfilment carried out on my behalf by a real-life Vladimir-Estragon. Yet reading Howards account, I realise he must be closer to the facts than I am; memory has bent the event into the shape I wanted it to assume.