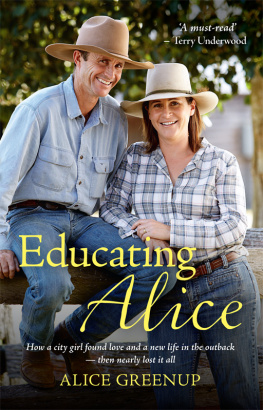

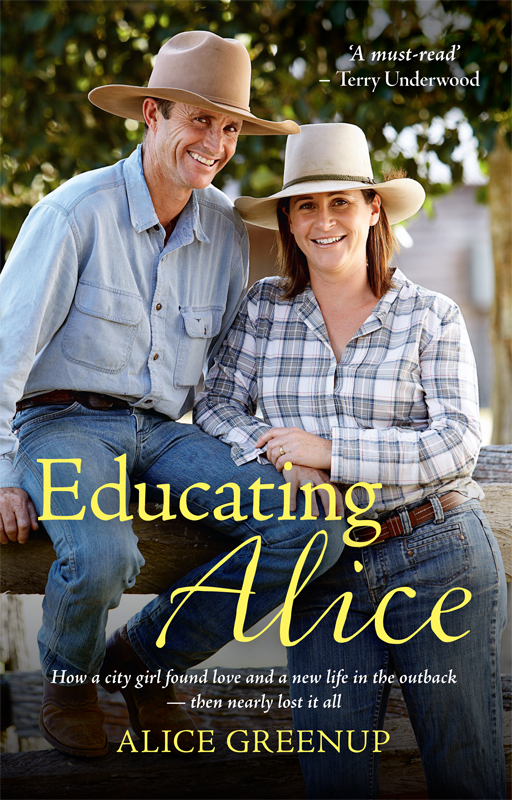

Across the table, Alice Greenups shining eyes and radiant smile dominated the celebratory dinner for winners of the 2006 MLA (Meat and Livestock Australia) and Australian Womens Weekly Search for Australias Most Inspiring Rural Women, of which I was an instigator and judge.

Now Alice has shared her remarkable journey with disarming honesty and at times confronting candidness. Her story is a must-read, an emotional feast. The Modern Melbournian Miss was never going to fit the mould upon marrying into a well-respected, long-established pastoral family. However, my fellow city convert and her land-entrenched man have survived against the odds and, through dogged determination, Alice has forged her own pathway to become a highly acclaimed rural leader. Educating Alice reveals the many intricate and challenging layers of life on the land, at a time when Australian farmers, who feed and clothe the world, remain undervalued. Passionate and unconditional love of land, livestock and each other are at the very heart of the lives of Alice and Rick and that of my family too.

The old cow glances up; unperturbed by my sudden appearance she resumes grazing, selecting the sweet new shoots of grass in preference to the dry tasteless stalks of last summer. Her three-month-old calf is playing further down the hill, where the gully opens up into a creek flat. He frolics with his three playmates; they chase each other through the long grass, skipping over rocks and logs of ironbarks that died in their prime, their demise hastened by fifteen years of drought. The landscape bursts with renewal after a wretchedly dry spring.

Better late than never, good January rain has liberated us from the treadmill of drought for how long is uncertain, but for now the water is still seeping from the hills, keeping the ground moist, the grass lush and the creeks trickling, and lifting our spirits with its promise. Our dams are full. There is a good body of feed, the calves are strong and sappy and the cows udders are bursting with creamy milk. Its going to be a ripper of a branding season.

Unaccustomed to water on the ground and flowing gullies, my horse snorts and paws at the strange phenomena. His body is tense. He twists and agitates as I urge him to cross a gully. The water is shallow and clean. I can see the bottom. But he is a young horse and at three years of age, born into the middle of the worst drought in living memory, he has seen little rain. Flowing water to him is as terrifying as a snake. His body is in flight mode. I rub his neck and talk to him, giving reassurance. Its the first morning of what is going to be a long week, mustering 700-odd cows with calves, with plenty of gullies and rivers to cross; he might as well get used to it.

Squeezing with my thighs, I urge him towards the grazing cow. He makes up his mind and commits himself, lurching forward, clearing the gully easily with a metre to spare. I land roughly in the saddle, his sudden leap taking me by surprise. He snorts again, still unconvinced that the water is safe. I tilt my weight forward, he takes my cue and we head up the rocky bank, his powerful hindquarters thrusting me to the fore of the saddle.

Seeing my proximity, the cow moves off quietly down the gully towards her calf. She lets out a warning, a low moan that tells him to stop playing and return to her side. Around the ridge the other cows stir and mirror her movements, meandering down the gully like rivulets merging to become a stream of cows.

Mac, go back. I accompany this command with a long low whistle to send my dog to the lead to block the cows momentum. A cream short-haired border collie, Mac stands out in the landscape and is easily spotted snapping at the cows, his pale coat contrasting with the deep reddish-brown of the herd, gleaming in the sun. The calves are getting their first education in respect. Step out of line and before they know it a cream blur will be nipping their soft brown muzzles. They soon learn there is safety in numbers and its prudent to toe the line.

The CB radio strapped to my chest crackles into life. You copy, Alice?

Copy, Rick.

How many cows have you got up there?

I contribute my tally and he calculates that we have them all 120 in this mob. A rendezvous point is arranged.

Mac, come behind.

My cows amble off to join the rest of the herd. Mac and I guide them by positioning ourselves on the wing of the mob, nursing them through the trees towards a clearing where the other stockmen, Shane and Lachlan, are converging with their respective mobs, gathering the cows and calves with Ricks in a corner of the paddock so we can get an accurate count. We have been riding for three hours and have completed the paddock in good time, with all cows accounted for. Were pleased to be so far along by mid-morning; to have mustered the cattle before the fresh, crisp air makes way for the stifling, sticky heat that builds as the shadows of the trees and hills shorten and the sun rises high into the sky. The cattle walk better in the cool and its much easier going for the calves.

Its a long walk for them back to the Jumma stockyards seven kilometres or more. Theres little point in us all going with the cattle, which are now relaxed and content and can be handled by two riders and a couple of handy dogs, so Rick sends Shane and Lachlan to muster an adjoining paddock while we walk the first mob back to the yards. We hand over our CB radios so they can stay in touch with each other we wont need them now; the hard part is done. The cattle are well controlled and weve done this trip many times. The rest will be a breeze.