A Oneworld Book

First published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2016

The ebook published by Oneworld Publications, 2017

Copyright Ruth Dudley Edwards 2016

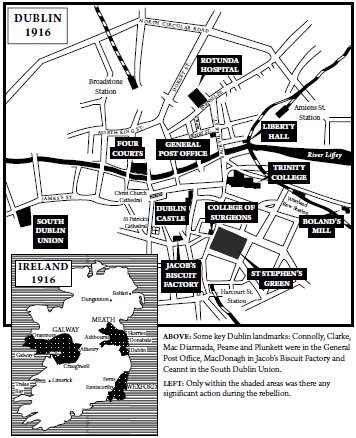

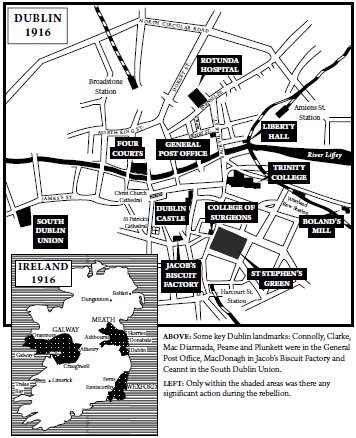

Map copyright Laura McFarlane 2016

The moral right of Ruth Dudley Edwards to be identified as the Author of

this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders for the use of material in this book.

The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions herein and would be

grateful if they were notified of any corrections that should be

incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-073-9

eISBN 978-1-78074-872-6

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

More Praise for The Seven

Fascinating and penetrating... Innovative and engaging... can be welcomed as an important contribution to the discussion and a

serious contribution to our understanding of an extremely complex and challenging period in modern Irish history.

Irish Independent

With its sharp observationsas well as its demystifying impulse and wry alertness to every nuance of 1916-symbolism, The Seven is an important book. It disentangles the strands of motivation and aspiration which previous generations had tended to lump together.

Times Literary Supplement

Dudley Edwards brings a forensic eye to these rebel lives.

Literary Review

... lively, readable, opinionated... she brings [the Seven] to life with empathy and zest.

Sunday Times

Dudley Edwards... clearly knows how to entertain as well as inform. This book feels like the result of a lifetimes research, neatly condensed into a colourful narrative that readers of all political persuasions should be able to enjoy.

Sunday Business Post

The sketches are succinct, sympathetic and sometimes mordantly funny.

Evening Standard

Written with great verve and zest, as well as judicious tough-

mindedness, Ruth Dudley Edwards The Seven is an overdue reexamination of the remorseless nationalist faith that led not only to the Easter Rebellion but to the Troubles beyond. For anyone keen on understanding why the question of Irish identity and Irish nationhood remains so vexed, Ruth Dudley Edwards study is essential.

Weekly Standard

[A] detailed examination of the seven signatories to the proclamation that launched the Rising... The authors deft character studies bring these larger-than-life figures down to earth and she explores their motivations and failings as well as their deeds.

Chicago Review of Books

Offers astute pen portraits of the leaders of the 1916 Rebellion. Her analysis of how these complex men, idealistic but also uncompromising, led a rebellion is a superb introduction to this period of momentous change in Irish history.

Colm Tibn

A provocative, personal, fascinating, and utterly readable contribution to a hugely important debate.

Richard English, author of Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA

A fine, well-researched and beautifully-written, ground-breaking book by a leader in her field.

Andrew Roberts F.R.S.A., bestselling author of Napoleon the Great

About the Author

Ruth Dudley Edwards is a leading commentator on Irish affairs in both the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. The author of several books on Irish history, including biographies of James Connolly and Patrick Pearse, she was awarded the James Tait Black Prize for her biography of Victor Gollancz. Ruth was born in Dublin and now lives in London.

To Owen, my brother

Contents

Introduction

As a child in Dublin in the 1950s, I was fascinated by the enormous picture over the fireplace in the bedroom occupied by my Grandmother Edwards, the devout republican in the family. Called The Last Stand , it was a portrait in the heroic style of a scene of carnage in the General Post Office during the last desperate hours of what was popularly known as the 1916 Easter Rising.

In the picture, Grandmother pointed out to me five signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic who had been murdered by the British. (She never minced her words.) There in the centre, lying on a stretcher, was Commandant General James Connolly, the spokesman of the poor who led the Irish Citizen Army, bravely bearing the terrible pain of his shattered ankle.

Beside him, gazing into the middle distance, was the visionary President of the Provisional Republic, Patrick Pearse; he was standing beside his devoted brother, Willie, who was not a signatory but who was executed anyway. Racing towards Connolly was the poet Joseph Plunkett, seriously ill but still intent on freeing Ireland. At the bottom of the stretcher knelt Sen Mac Diarmada, Connollys adjutant, and peeping self-effacingly from behind the Pearse brothers was the moustachioed Thomas Clarke. (Thomas MacDonagh and amonn Ceannt, the other two signatories, were fighting elsewhere, but posters showing the Proclamation headed or surrounded by headshots of seven men were ubiquitous.)

Occasionally, Grandmother would arrive home in late afternoon and announce portentously: I have had tea with Mrs Tom Clarke and she says the Pearses think they own 1916. I did not really follow what this was about it would take a while for me to grasp that men I had been told were heroes and martyrs were not mythical beings but real people with living relatives who were not always in harmony.

In my primary school, where teaching was through Irish and the ethos was intensely patriotic, there were reverential references to ir Amach na Csca (the up-rising at Easter) or Aisir na Csca (literally, the resurrection at Easter) as the heroic climax of 800 years of nationalist struggle. We were told that afterwards there was a war of independence against the British, which we won. History seemingly came to an end in 1921.

We were told nothing at school about the casualties of 1916 or the subsequent war: the dead who mattered were those executed by the British, particularly Patrick Pearse. Nor were we told about the bitter civil war following the Anglo-Irish treaty, or the seventy-seven men executed by Free State forces. And if Northern Ireland was ever mentioned, it was as a bit of Ireland that was ours, and we would get it back some day. No one ever seemed to go there or know anything about it.

I was better informed than most because my parents talked at home about such inconvenient facts as civil war fatalities, sundered families and vicious political divisions, the involvement of many Irishmen in the British Army in the two world wars, and their view that Protestant unionists deserved our respect. Unlike the IRA and fellow-travellers like my fascist grandmother, they had also been unequivocally anti-Nazi.

It was Patrick Pearse who most fascinated me, because we were told he was the noblest man in Irish history and that he could be canonized someday, yet no one seemed to know anything about him. One friend was taught in her middle-class convent school that Jesus and Pearse were the only two men in the history of the world who were exactly six feet tall. That kind of nonsense made me want to find the real man. I wrote a student paper about Pearse as an educationalist and in 1964 I tried and failed to find enough material to write a masters thesis about him. The following year, a new cathedral consecrated in Galway city had a side chapel where the image of the risen Christ was flanked by mosaic representations of Patrick Pearse and John F. Kennedy praying to him. Both of them, along with favourite popes and saints, were on many an Irish nationalist mantelpiece.

Next page

![Lorcan Collins [Lorcan Collins] - 1916: The Rising Handbook](/uploads/posts/book/143326/thumbs/lorcan-collins-lorcan-collins-1916-the-rising.jpg)