For my family.

Zeitlin, Richard H.

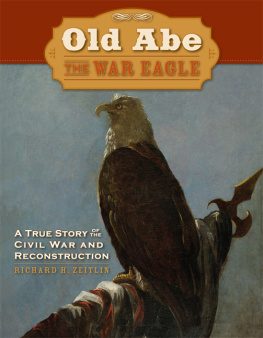

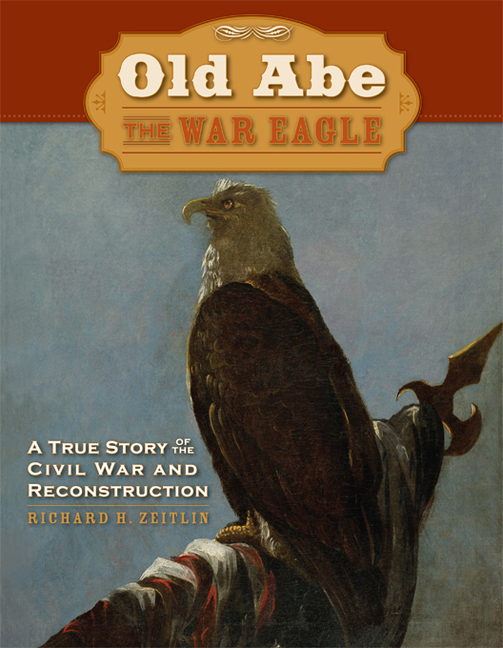

Old Abe the War Eagle.

Bibliography: p. 108.

1. United StatesArmy. Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, 8th (18611865)Mascots. 2. WisconsinHistoryCivil War, 18611865Regimental histories. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Regimental histories.

I. Title.

E537.5 8th.Z45 1986 973.7475 8526126

ISBN 0-87020-239-1

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Society's collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Preface

THIS is the story of a famous bird, of the men who bore him off to war, and of what happened after the guns fell silent. It is in many respects an incredible story, but it is trueas true, at any rate, as a careful sifting and winnowing of official documents, contemporary letters and diaries, newspapers, and eyewitness accounts can make it. It is the story of Old Abe, Wisconsins War Eagle, mascot of the Eighth Regiment of Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, living symbol of the Union at war.

Old Abes life contained so many imagination-capturing experiences that storytellers, both at the time and later, have outbid one another by turning the eagle into a legendary hero possessed of amazing attributes. Old Abe has become a creature of folklore and fairy tale, and the historical facts surrounding his existence have gradually become encrusted with sheerest fantasy. Over the years, Old Abe has received acclaim for saving the day at certain battles, for delivering crucial airmail messages, for disrupting enemy attacks, for leading his invincible comrades to victory, and even serving as the objective of Confederate strategy.

Old Abe stories have appeared and reappeared in a wide variety of publications, beginning in the 1860s and extending to the present day. Journals as diverse as Natural History and True Magazine have carried features on his exploits. Poems and songs celebrated Old Abes imaginary feats. He is a staple with newspaper feature writers and authors of childrens stories. Discussions supposedly proving that the eagle was female, and therefore an important contributor to the womens rights movement, began in 1889 and have continued to this day. Clearly, there is something in the Old Abe legend that interests people.

In some ways, of course, Old Abe was a pitiable creature. Secured by a strong cord to a crude perch atop a wooden pole and carried to dangerous locales by a succession of eagle-bearers, Abe did not have much say about his own itinerary. People clipped his wings repeatedly, and the captive bird could never fly any great distance. Old Abe was never free to soar as eagles do. For sixteen years after the Civil War ended, he dwelt in a cage in the basement of the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madisonhardly an example of liberty.

Yet Old Abe was also a veteran of thirty-seven battles and skirmishes. Along with the Wisconsin boys of his regiment, he participated in the campaigns which opened the Mississippi River and assured Federal domination of the nations watery highways. Along with nearly three million largely volunteer citizen-soldiers from the North, Old Abe fought a determined, valiant foe in a titanic four-year conflict that ended slavery, preserved the Union, and helped to usher in the modern industrial age. The agony of the Civil War, its enormous sacrifices and its terrible human costs, were borne willingly by most Northerners, including the people of Wisconsin. Old Abe became a symbol of those momentous events, capturing the imagination of his own and of subsequent generations. He become a symbol for bravery and sacrifice, first in Wisconsin and then in the North as a whole. At a time when telegraphic communication was new, and radio nonexistent, Wisconsins war eagle became what would later be termed a media hero.

But what made Old Abe so famous and so much-beloved? He was not the only animal or even the only eagle that went to war. A Minnesota regiment and the Twelfth Wisconsin Infantry both had half-grown bears as mascots. The Forty-Ninth Illinois Infantry had two gamecocks of the first class breed. Badgers and raccoons, stuffed and otherwise, were dragged along as mascots by Civil War soldiers. A wildcat accompanied a Confederate regiment from Arkansas to the Battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862. The Forty-Ninth Wisconsin Infantry acquired a golden eagle when it garrisoned a post in the Far West at the close of the war. Numerous dogs followed both armies. A bald eaglethe official national birdobviously had advantages over dogs and bears, no matter how amusing or ferocious the latter may have appeared. The eagle had long symbolized American hegemony. With fierce eyes and outstretched wings it proclaimed the Union on posters, broadsides, letterheads, buttons, coins, signs, and the mastheads of newspapers. In a metaphorical sense, the eagle was (in Daniel Websters words) the Union, one and inseparable, now and forever.

Also significant is the fact that Old Abes fame grew after the war. Adopted and supported by the State of Wisconsin, he traveled back and forthacross the country, borne now by members of veterans organizations. Like the so-called bloody shirt and a generation of ex-soldiers with missing limbs and eyes, Old Abe reminded all who saw him of what the North had fought for in 18611865, and who the enemies of the Union had been. He became Wisconsins ambassador at national celebrations such as the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia (1876); he was an extraordinarily successful fund raiser for health-care facilities as well as for the preservation of historic buildings and landmarks; he was a fixture at parades, conventions, and political rallies. Talented artists (and some manifestly untalented ones) painted his likeness. Photographers discovered him early in the war; it took sculptors a bit longer to begin immortalizing him. Even in death, Old Abe continued his storied existence, thanks to the taxidermists art. And of all Wisconsins heroes of the Civil WarEdward Bragg, doughty commander of the Iron Brigade; Joseph Bailey of Red River fame; Frank Haskell, chronicler of Gettysburg; Lucius Fairchild, the one-armed governorOld Abe remains the best known, the most fondly remembered, even a century afterward. It brings a smile to the historians face to say it, but, as a historical figure, Old Abe has impressive credentials.

He is significant, however, mainly in the context of human affairs. The story of Old Abe the War Eagle is properly the story of the men among whom he lived: the farmers, loggers, clerks, and immigrants who flocked to the colors in 1861. Therefore, this work focuses on the Eighth Regiment of Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, a body of about one thousand officers and men embedded in the vastly larger mechanism of the Union Army in the Western Theater of Operations. These citizens-turned-soldiermost of them young, not all of them braveexperienced much the same things that members of other Union regiments did: boredom, fatigue, endless marching and countermarching, the agonies of disease and sickness, the sudden terror and exhilaration of combat. What differentiated the Eighth Wisconsin from all the other regiments was their eagle, and their eagle helps make their story worth telling. A century ago, Old Abes notoriety called attention to their accomplishments as soldiers. Today, Old Abes lasting fame provides a window through which to view the fiery drama and tragedy of the Civil War and its aftermath.