Contents

Guide

Page List

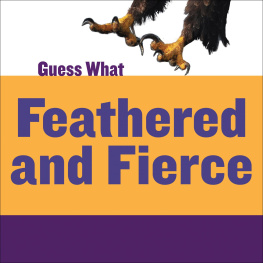

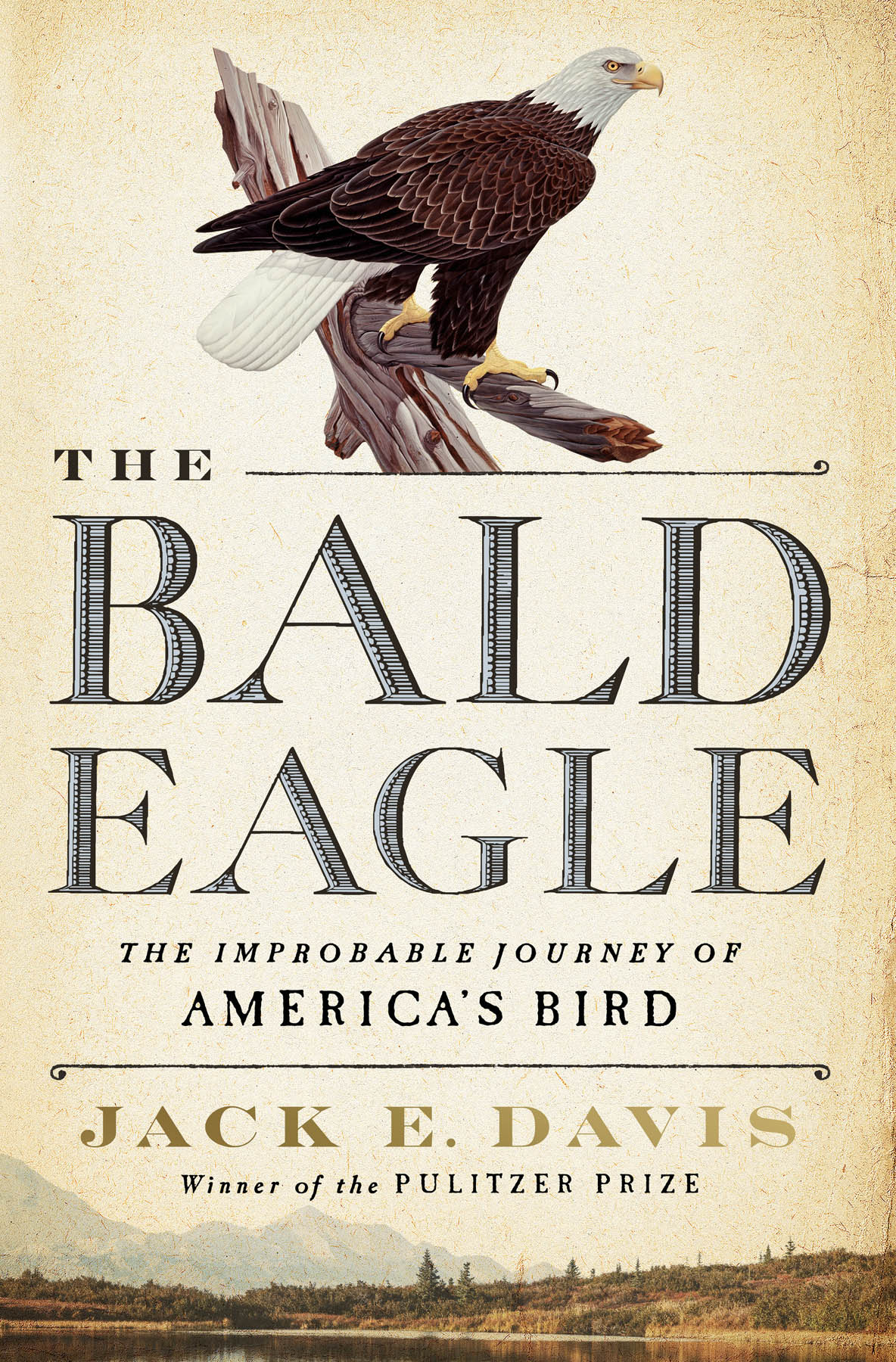

THE

BALD

EAGLE

The Improbable Journey

of Americas Bird

J ACK E. D AVIS

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A D IVISION OF W. W. N ORTON & C OMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

To the memory of Marina Powdermaker

and Geoff Sutton

In an eagle there is all the wisdom of the world.

John Fire (Lame Deer), in Lame Deer, Seeker of Visions

CONTENTS

THE BALD EAGLE

S TANDING AT THE ROCKY EDGE OF A STREAM, A BALD eagle scans its surroundings with luminous eyes. Satisfied, it unfurls its wings straight up, drops into a crouch, and, in one fluid motion, pushes skyward, sweeping its seven-foot wingspan out and down. The eagle rises, slowly at first, legs and feet hanging like pendants. Its powerful wings beat hard against the air, and it continues to rise. Limbs draw up for the journey ahead.

Nesting season has come to its inevitable end, and migration has begun. As fall slips toward winter, bald eagles across western Alaska have been called to a distant place, a place they pursue annually throughout their lifetimesas did their ancestors in their lifetimes. Their autumnal exodus from seasonal territories proceeds not in a mass or in crowded waves. There are no herding calls sounded to a group, no flocks gathering for takeoff, no wedges of flight piercing the sky. Instead, each birdeven the young ones not long from the nestfollows its own impulse to leave, and over a period of weeks, thousands of eagles set out individually on a solitary journey duplicated by multitudes.

Seeking a southwesterly course, wind in their faces, sun on their backs, they eventually roll out over the Aleutian Islands. Each island in the trackless sea below is an ancient link in a migration route mapped in the eagles evolutionary memory. Tracing it from several hundred to several thousand feet up, they continue to fly solo, loosely spaced a half mile or more apart in streams twenty to thirty miles long, soaring on favorable winds where they exist and pumping wings providently where they dont.

Each passing day grows stingier with light, granting barely six hours between the dim interludes of dawn and dusk. Well before sunset, the journeying birds descend to some remembered resting place en route. They fish for renourishment and then settle down in trees or on rock ledges for the night. The next morning, they fish again and then lift above the dewy haze one by one to push on. If the weather is clear, these daylight fliers will travel a hundred or more miles before another night of rest.

A favored stopover is the island of Amaknak, a four-day journey from their mainland territories, if they dont linger. Amaknak is also the final destination and winter residence for many of the eagles. As it comes into sight, they wheel toward its green and rocky hills.

On descent, primary flight feathers splay and twist; tail feathers pitch upward and downward. Horizontal wings dance on fickle air currents. Heads dip forward, and keen eyes pick out landing spots as each nimble bird floats in. Legs reach down and toes spread to meet the upward-surging ground in a near balletic landing. Wings close as a final bow.

M IGRATING FROM ONE PART of Alaska to another doesnt seem like much of a winter retreat, but bald eagles can tolerate cold weather. What they cannot abide is thick ice that prevents them from catching fish. The coastal waters around Amaknak dont freeze solida fact well known to them. Not only are fish accessible, but so, too, are tens of thousands of wintering waterfowl, easily pluckable fare. If the winter prospects are plentiful a few hundred miles away, why should an eagle from the hyperborean climes of Alaska bother to fly as far south as Washington or Oregon or, as some mystifyingly do, all the way to New Mexico?

The migrators that arrive on Amaknak join hundreds of balds that reside there year-round. Food that is abundant in the winter is even more so in warmer months. On a map, the Aleutian chain looks like a trail of breadcrumbs that falls away from the mainland in a southwestward arc. The islands create an archipelago divide between the Bering Sea and the North Pacific Ocean. The convergence of these two waters stimulates a gushing wellspring of marine life that draws to Amaknak some forty million spring- and summertime nesting seabirdsshearwaters, kittiwakes, fulmars, petrels, cormorants, and albatrosses. Balds nest alongside them.

At 3.3 square miles, Amaknak is one of the larger of the breadcrumbs. On its north side looking out to the Bering Sea is Iliuliuk Bay, which was once an undisturbed natural habitat of seals and sea otters and the pre-European home of Unangan, the indigenous people of the region. By the late eighteenth century, the island had become an outpost of Russian fur traders, who called the Natives Aleut. They also named the bay Dutch Harbor, yet there is no reliable evidence that the Dutch ever settled their namesake water. Perhaps the Russians first heard about Amaknak Island from Netherlander whalers or seal and sea lion hunters who would slip into the protected bay to trade with the Native peoples and take on fresh provisions or escape storm-ravaged seas.

Dutch Harbor is wrapped in the protective embrace of conical hills that range from a few hundred to more than a thousand feet in height. They are the kind of hills you might imagine on a volcanic island, which Amaknak is. Unpopulated by humans, they are treeless yet green with vegetation when not white with snow. In the summer the green spreads like a lush quilt embroidered with red salmonberries, purple orchids, yellow-green honeysuckles, and chocolate-brown chocolate lilies. Exposed rock in the hills adds shades of gray, brown, blackish brown, and rust.

There is plenty of rust of the iron oxide kind around the island too, where the air is perpetually wet and salty. Up in the hills, rust is found on the metal hardware of old gun batteries from World War II (the Japanese bombed Dutch Harbor twice), but most of it is down around the harbor. Its on trucks, cars, chain-link fences, and manhole covers. Its rubbed to a burnish on handrails, door handles, and steel stair treads. Its on loading cranes, shipping containers, and crab traps. Its on the winches, booms, anchors, and bulkheads of fishing trawlers. It bleeds down the sides of their deckhouses and hulls.

For as long as Dutch Harbor has existed in name, it has been a commercial fishing port, and a phenomenally productive one at that. In 2005 the Discovery Channel began filming the reality television series Deadliest Catch at Dutch Harbor, following snow- and king-crab fishing boats and crews out into the cold and often turbulent Bering Sea. In 2020 the networks most popular reality show filmed its sixteenth season, and Dutch Harbor finished the year as the top commercial fishing port in the United States for the twenty-fourth consecutive year.

The bald eagles may be blind to the film cameras, but Dutch Harbors commercial success doesnt elude them. The 700800 million pounds of fish and shellfish hauled into port are another call to the eagles winter migration. Like pelicans and gulls, balds will eagerly take a free offering coming their way.