DEDICATION

To Marjorie, my lifes copilot, without whom my

trips around the sun would be meaningless.

Contents

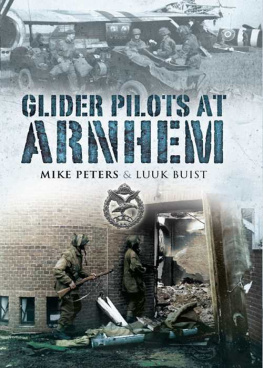

For decades I walked past them in the cereal aisle at the grocery store with hardly a glance. Older men looking for the Cheerios. I couldnt have known that some were anonymous heroes who had served and unfathomably sacrificed in World War II.

When I joined other community leaders in 1996 to bring the decommissioned USS Midway aircraft carrier to my hometown of San Diego to become a museum, I had no indication that I was embarking on a personal mission to preserve the legacy of those who serve and sacrifice for our country. To unveil their stories on a far more personal, intimate level than most history books. A mission that has become a driving force in my life.

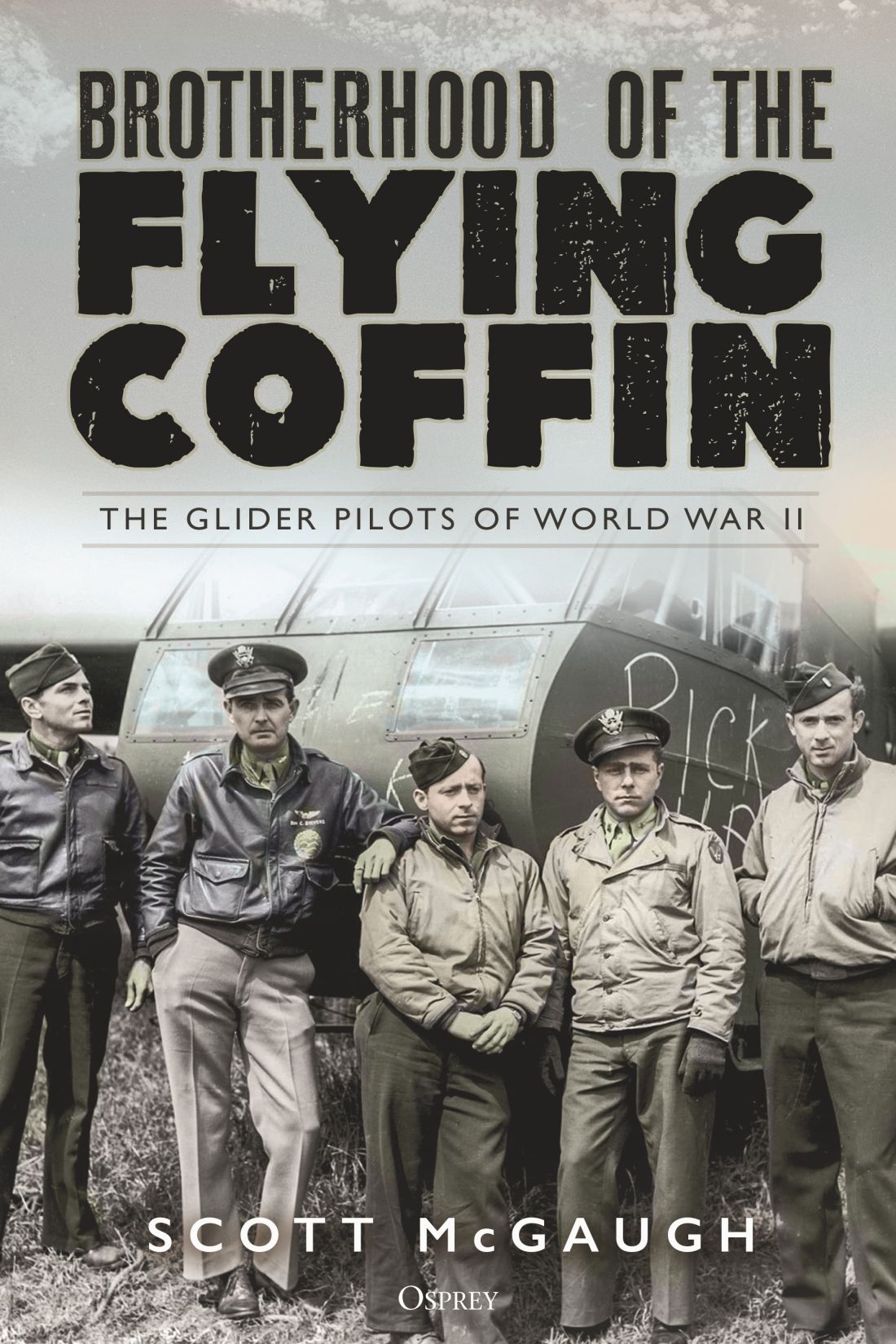

Brotherhood of the Flying Coffin is my 11th book on that journey, while serving the last twenty-five years first on the USS Midway Museums board of directors, then as founding marketing director, and then again on the board. Twin passions that hopefully will inspire future generations by the estimable value of serving country and community.

Novelist Ray Bradbury once said, First, find out what your hero wants, then just follow him. Indeed, getting to know these men from their boyhood, unveiling their grit, their dreams, and discovering the invisible scars they have carried has changed my life. To share both their pain and achievements inspired me to write my first book in 2004, then the next, and the next.

I hope this latest instalment will be as worthy of your time as much as it has meant to me.

This book is the story of the young men who left lumber mills, girlfriends, family farms, sales jobs, coal mines, their children, parents, or perhaps college for war. It focuses on their individual legacies that became the personal mosaic of World War II in Europe, not a history of their squadrons, troop carrier groups, air wings, or troop carrier commands. Other authors already have admirably chronicled what are commonly called wartime unit histories.

It is in that spirit Ive focused more on the glider pilots experiences, rather than unit identifications and military orders of battle. For example, focusing more on glider pilot James Larkins four combat missions than whether he was assigned to the 84th Squadron, or if he was part of the 437th Troop Carrier Group (TCG), and whether his TCG was part of the 52nd or 53rd Air Wing. Specific references to a unit are used only when they are helpful for the reader to keep track of the pilots experiences.

To be sure, this is not to overlook the vital contributions of various military units, but only to keep the focus on the young mens legacy.

Similarly, I steered clear of military acronyms, Roman numerals, and where or when an individual might be transferred to another unit or base on temporary detached service that would require explanation and blur their story. War is chaotic, and this books aim is to stay centered on the lives of those young men from West Virginia, the Texas panhandle, and the California foothills.

Likewise, rank can become muddling at times. With few exceptions, glider pilots held a flight officer, 2nd lieutenant or 1st lieutenant rank. A pilot could have been promoted between one mission and the next, or, he may have held his graduation rank of flight officer throughout the war. Extant records are not always clear or do not include what rank a glider pilot held at the precise time of a particular quote or combat experience. So, in the interest of clarity, Ive included a documented rank reference generally in the first or second detailed combat inclusion and then glider pilot thereafter.

Again, this is not out of any disrespect for anyones rank but keeps a laser focus on their experiences in the course of more than 250 specific glider pilot references throughout the book. In the case of senior officers (generals, captains, and majors), rank has been included when it was essential to illustrating roles, decisions, and relationships.

Glider pilot mission narratives understandably do not always match military historical documents. A glider pilot may be listed in unit records as eighth in line when taking off but reports after the mission indicated he was behind the flight leader when they reached the landing zone. In such cases, I generally relied on the pilots personal reports.

Combat statistics and official unit narratives (and even the time of day in war) can be as fluid as a battles front line. Official US Army primary-source documents frequently differ on how many men, the tons of equipment, or how many howitzers a glider mission delivered to the battlefield. Or how many glider landings in a designated area made it a successful mission. Even the number of participating glider pilots can be a moving target from one source to the next.

Again, in service to the reader, Ive either used the most-cited figure or have conservatively rounded off a range of statistics to more than or nearly simply to make a point and get back to their story.

Regrettably, very few World War II glider pilots are with us today. Those who remain now are in their mid-nineties or older, making reliably accurate interviews problematic. Yet this book remains as much in their words as possible.

As the decades passed, a glider pilot may have in various combinations recorded his oral history for the Library of Congress or another museum, contributed his personal writing to the Silent Wings Museum in Lubbock, Texas, been included in various books over the years, and been quoted in Stars & Stripes in 1944, Yank magazine in 1945, or in a 50th anniversary article in his local newspaper in 1995. In some cases, hes told his story to a family member who has written it for posterity. In other instances, his family has kept and treasured his diary, war records, log books, newspaper accounts, and letters.

For the sake of clarity and to keep the story moving, in instances of redundant sources I have often employed a Darlyle Watters personal account citation with general information on the source or multiple sources of his account.

A glossary of aviation-related terms is included at the end of the book, also in the interest of keeping the story focused on these American heroes. The 24-hour, military-style clock is used for convenience.

Finally, I elected not to go into great detail about the role of British gliders in the European Theater of Operations, the ongoing research and development of American combat gliders during the war, or some of their ancillary missions, experiments, or post-battle operations. Each has been ably chronicled by other authors.

All so that the reader may sit in a gliders copilots seat in the largest airborne assaults of the war, complete each mission, and, for the lucky ones, somehow find a way to return home.

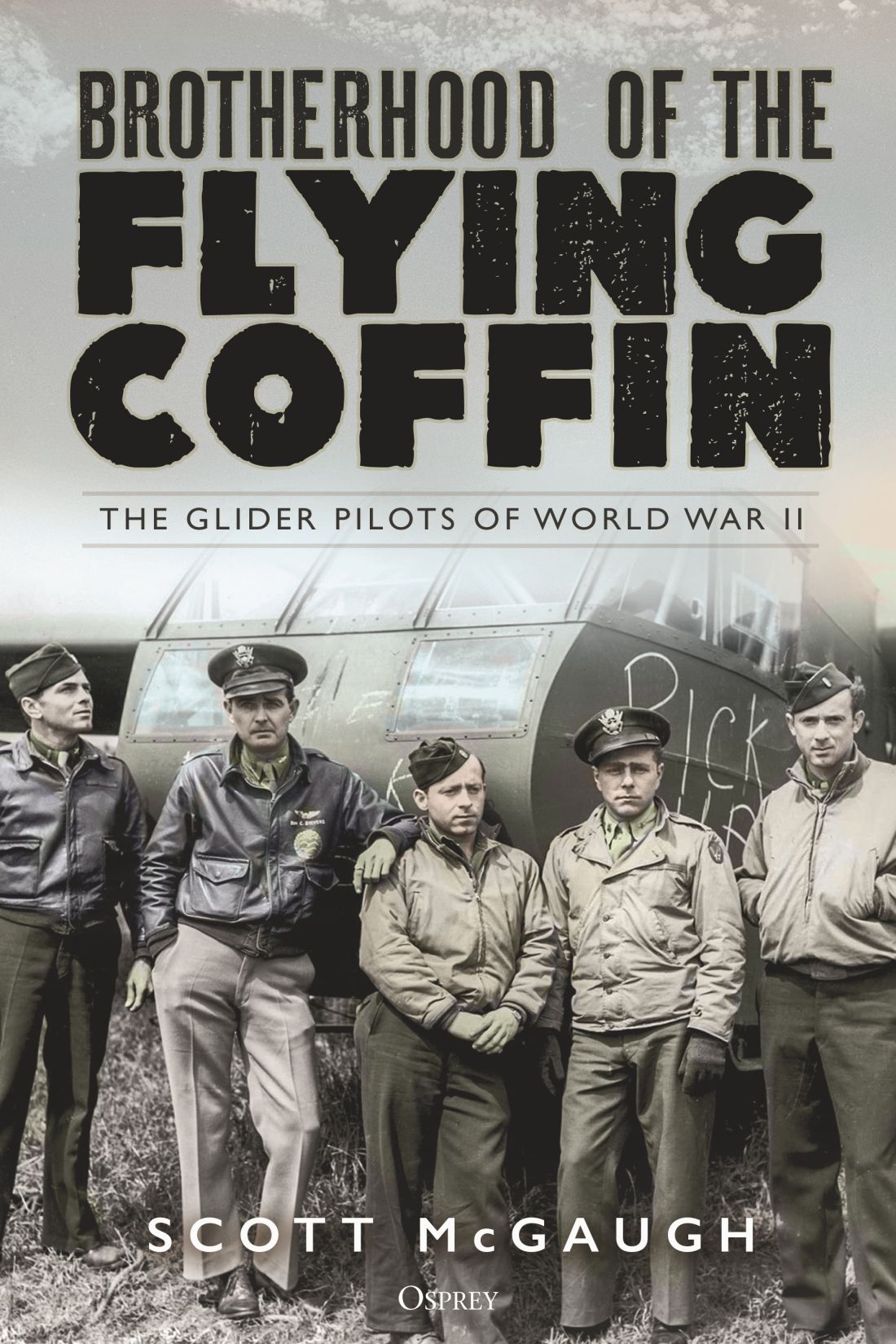

They were farm boys. Class presidents. Grocery baggers. Pranksters. Pre-med students. Shelf stockers. Reservists. They volunteered to fly an aircraft not yet invented into war; one that would be skinned with fabric but carry no guns, no engines, and no second chances. They were the volunteer glider pilots of World War II. They led the Greatest Generation into battle in Europe, setting standards of bravery and self-sacrifice that both frighten and inspire us to this day.

Next page