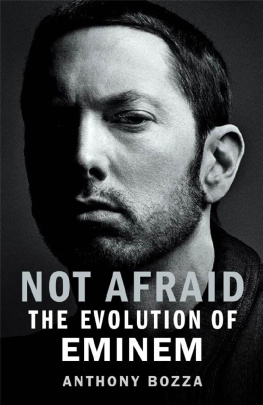

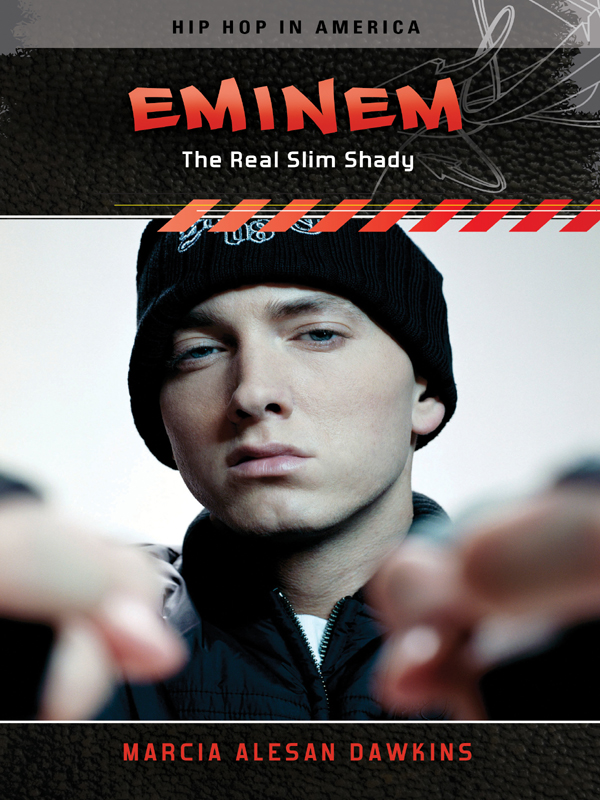

Eminem

Recent Titles in

Hip Hop in America

The Wu-Tang Clan and RZA: A Trip through Hip Hops 36 Chambers

Alvin Blanco

Free Stylin: How Hip Hop Changed the Fashion Industry

Elena Romero

Eminem

T HE R EAL S LIM S HADY

Marcia Alesan Dawkins

Hip Hop in America

Juleyka Lantigua-Williams, Series Editor

AN IMPRINT OF ABC-CLIO, LLC

Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England

Copyright 2013 by Marcia Alesan Dawkins

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dawkins, Marcia Alesan.

Eminem : the real Slim Shady / Marcia Alesan Dawkins.

pages cm. (Hip hop in America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-313-39893-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-313-39894-0 (ebook) 1. Eminem, 1972Criticism and interpretation. 2. Rap (Music)History and criticism. I. Title.

ML420.E56D38 2013

782.421649092dc23 2013012390

ISBN: 978-0-313-39893-3

EISBN: 978-0-313-39894-0

17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook.

Visit www.abc-clio.com for details.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

To the Real Slim Shady in All of Us

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book was born in Queens, New York. And this book, of course, is not my work alone. I discussed earlier versions of these thoughts and arguments in lectures or workshops at Harvard University, Brown University, the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Vanderbilt University Law School, Belmont University, Lipscomb University, Villanova University, Simmons College, Emerson College, the University of Southern California, and the University of California, Los Angeles. I also made presentations based on the research for this book to the annual meetings of the National Communication Association and the American Studies Association. And, as always, I had the benefit of many meals and coffees with my colleagues over the years at Brown University and USC Annenberg, including Larry Gross, Ernest J. Wilson III, Randall A. Lake, Stacy L. Smith, Chris Smith, Bob Scheer, Duncan Williams, Marcus Shepard, T. J. McDonald, Omar Bahgat, Ryan Houston, Ulli Ryder, Evelyn Hu-Dehart, Janet Cooper-Nelson, Tyler Rogers, Alex Agloro, and Patricia Balsofiore. I have also benefitted from close and careful readings of the draft by Ebony A. Utley, Sadiqua Hamdan, and Ric Whitney. My utmost gratitude goes out to Daniel J. Sharfstein, for giving me access to his brilliant legal mind as well as the archives at Vanderbilt University Law School; to Sybril Bennett, for her admonitions that disruption did not start and cannot end with Eminem or hip hop; to Joe Lopez (aka DJ Bazooka Joe), for tuning my ear to the frequency of Eminems sonic artistry; to Rafael Matos Sr., for opening my eyes to Eminems prophetic rhetoric; to Jeff Hall, who made me feel it was okay to admit that Kill You is my real favorite Eminem song; to Lisa Rueckert, who gave me a vision for this project, literally; to Ramon Fuertes and Zana Bru, for their entrepreneurial encouragement; to Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman and Craig E. Carroll, for their intellectual contributions via personal interview; to Lisa Corrigan, for her firm admonitions that feminist women love Eminem; to David Hino, for his meditations on love and hate; to J. Z. Matthews, for her gentle reminder to look for a bigger definition of justice; to Shoshana Sara and Maysa Gayyusi, who listened to and talked about Eminem with me in Jerusalem and Ramallah, respectively; and, to the amazing Marshall Bruce Mathers III himself, who, despite not knowing that I exist, will always be my muse.

Finally, and most important, I give thanks to my family and friends for their willingness to listen to Eminems music with me religiously and to deal with the potty mouth I developed as a result. I thank my closest friends, Jason S. Woodson, Ivette Lora, Shinina Butler-Nance, and Zainah Alfi Mir for telling me I could do it. I thank my sister, Lindsay, for reminding me that theres a little Slim Shady in everybody. I thank my parents, John and Olga, for instilling in me a love for music and art of all kinds. I thank my cousin, Kate Breen, for her spirited conversation. I thank Harry Guillermo Mendoza, not only for the gifts of time and space to embark upon this project, but for helping me see the relationships among the material, social, and spiritual aspects of myself. And, most of all, to my readers, thank you for your interest in my take on the real Slim Shady.

Prelude

My fascination with Eminem was solidified when The Slim Shady LP hit record stores on February 23, 1999. However, The Slim Shady LP and its lead single My Name Is werent my first exposure to the controversial artist or his work. Eminem caught my ear a year earlier when I was at New York University (NYU) writing my masters thesis on the rhetoric of underground hip hop. While I dissected lyrics written and delivered by the likes of Company Flow, Natural Resource, BlackStar, J-Live, and Shabaam Sahdeeq, I came across a single released by Rawkus Records called 5 Star Generals (1998) on which Eminem made a guest appearance. I would later learn that this was an old track the rapper recorded for cash and then forgot about while he was unsigned. Nevertheless, Ems first lines about sinning boldly by shooting nuns in Bible class and damning hell itself hit me like a ton of bricks. But, in an effort to be fair, I suspended my critical impulse and resisted the temptation to take offense from a literal interpretation of his words. After all, my research taught me to attend to what rappers shouted as much as to what they whispered. To me, Eminems lines sounded like a raised middle finger, a declaration that expressed a defiant and angry identity. And I knew that lines like his, which were sure to engage and enrage his listeners, would make him famous and infamous.

To my surprise, my 89-year-old Cuban American grandfather, Rafael Matos Sr., a poet and a reverend, heard something exciting in Eminem too. I stopped by my grandfathers house in Hollis, Queens, on my way home from NYU around the time the video for My Name Is was in heavy rotation on MTV. I could hear the song blaring from his television. This struck me as strange for two reasons. First, my grandfather wasnt fluent in English, so he was more inclined to watch Spanish-language channels like Univision. Second, hed never expressed much interest in rap music other than commenting that he noticed kids rapping in the parks near his house every now and then. Of course, I knew Because my grandfather didnt know that, I was surprised to catch him watching English-language rap videos. When I entered the living room my grandfather sat transfixed. After the video ended, I asked him if he knew what he was watching. Sitting up in his blue La-Z-Boy recliner he said, Im watching some guy who calls himself Eminem. I can tell hes probably a heathen and I dont care. I love what hes doing with his words. I was shocked. My grandfather went on to tell me that despite the obvious language and experiential barriers that stood between him and Eminem, he was in awe of the way the rapper was using his voice and his words as instruments. And what really got me was when my grandfather said that Eminems unapologetic tone reminded him of many preachers fiery delivery over the years. I could not believe it. Grandpas encounter with Eminem was spiritual.

Next page