CONTENTS

Thanks to my family: my mother Joan for her encouragement, reading through the book at various stages, and for her suggestions; my wife Zsuzsanna and father Roy for all their help and support.

Thank you to Dunja Sharif of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, for help and assistance with accessing the Hogan collection of Wallace material. Thanks to Roger Wilkes for his work on listing all the material.

Thanks to my commissioning editor, Mark Beynon, and all who have worked on the book at The History Press.

All biographers owe a debt to those who have written about the subject previously, and I would like to thank Selina Hastings, daughter and literary executor of the late Margaret Lane, for kindly giving me permission to quote, without restriction, from her mothers 1938 biography of Edgar Wallace and also to reprint photographs from the book.

Thank you to Swami Dayatmananda of the Ramakrishna Vedanta Centre, Bourne End, Buckinghamshire for permission to include a photograph of what used to be Edgar Wallaces house, Chalklands. Thanks also to Wheeler Winston Dixon and Sharla Clute of the SUNY Press and Mr Duff Hart-Davis for permissions. With grateful thanks to Reverend Michael Boultbee for permission to include his letter about his childhood recollections of Edgar Wallace, written in 1975.

I am grateful for the advice of Sir Rupert Mackeson and the Society of Authors.

I am indebted to the British Library, British Newspaper Archive, Jonathan Horne (special collections) at the University of Leeds, and the special collections at the University of Sussex and Oxfordshire Library services.

Truth is stranger than fiction, and has need to be, since most fiction is founded on truth.

Edgar Wallace, The Man Who Knew , 1919

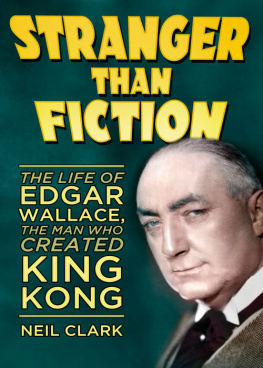

It is one of the most famous scenes in motion picture history. A gigantic ape, roaring defiantly, stands at the top of the Empire State Building and is attacked from all sides by fire from circling aeroplanes. King Kong caused a sensation when it first appeared on cinema screens in 1933, becoming the first film to open at the worlds two largest theatres the Radio City Music Hall, and the Roxy, in New York simultaneously. The Strangest Story Ever Conceived by Man the greatest film the world will ever see, the publicity declared. For once the catch-lines were right, wrote film historian Denis Gifford, in the history of horror movies, indeed of movies, King Kong still towers above them all.

More than eighty years on, the story of how the eponymous gorilla is captured on a remote island and taken to New York, where he escapes and causes havoc, still packs a punch. Its not just a thrilling adventure tale and horror story, but a romance too a modern reworking of Beauty and the Beast that never fails to touch our emotions. There have been two film remakes, in 1976 and 2005, and a new musical version opened in Melbourne, Australia, in 2013 to widespread critical acclaim. In 1991, the 1933 film was deemed to fit the criteria of being culturally, historically or aesthetically significant by the US Library of Congress, and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. But, while almost everyone knows the story of King Kong , and its place in cinematic history is assured, what is less well known is the almost equally fantastic tale of his English co-creator, who tragically died in Hollywood at the moment of his greatest and most enduring success. Writing the screenplay for Kong was the last major piece of work for Edgar Wallace, a man who packed into his relatively short time on earth enough achievements and experiences to fill several lives over.

Wallace worked as a printers assistant; a milk roundsman; a newspaper seller; a plasterers labourer; a soldier; a ships cook and captains boy on a Grimsby fishing trawler; a boot and shoe shop assistant; a rubber factory worker; a newspaper reporter; a foreign correspondent; a racing tipster; a columnist; a special constable; and a film producer and director.

The illegitimate son of a travelling actress, who left school at the age of 12 with no formal qualifications, he was also, at one point, the most widely read author in the world. Wallace made his name writing fast-paced thrillers, detective stories and tales of adventure. He wrote more than 170 books, and his work was translated into more than thirty languages. More films were made from his books than those of any other twentieth-century writer. He was the publishing sensation of the 1920s in one year in that decade, one out of every four fiction books bought in England was by Edgar Wallace. If that wasnt enough, he also wrote twenty-three plays, sixty-five sketches and almost 1,000 short stories. Wallace brought the art of popular entertainment to a pitch which never before had been achieved by any other writer, wrote his 1938 biographer, Margaret Lane.

Edgar Wallaces work was devoured by people of all classes, nationalities and political persuasions. Among his millions of fans were King George V, British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, a president of the United States, and a certain Adolf Hitler who, it is said, owned copies of all of Wallaces books.

The man born in poverty in south-east London, and whose mother gave him away to foster parents when he was just over a week old, became one of the biggest celebrities in Britain in the first third of the twentieth century.

He cut a flamboyant figure, chain-smoking cigarettes from his trademark 10in-long cigarette holder and being chauffeur-driven round London in a yellow Rolls-Royce. Wallace worked hard and played hard and was renowned not just for his industry but for his incredible generosity which knew no bounds. It was this open-handedness which meant that, despite his high income, Wallace died heavily in debt. However, he wouldnt have minded too much as he was a man with big ambitions who did everything on a grand scale. The covers of his books often carried the proud boast of the publisher: It is impossible not to be thrilled by Edgar Wallace. As I hope to prove, it is also impossible not to be thrilled and inspired by Edgar Wallaces extraordinary life story.

He lived for some extraordinary reason in Greenwich, in a side street that runs parallel with the river.

Edgar Wallace, The Twister , 1928

The year 1875 was one of the most eventful of the Victorian era. It was the year that Britain acquired a majority interest in the Suez Canal, Captain Webb became the first person to swim the Channel, William Gladstone resigned as Liberal Party leader and Gilbert & Sullivans earliest surviving opera, Trial by Jury , was premiered. Although life was still harsh for most people, things were improving at least for those living in towns and cities.

Among the important pieces of legislation passed that year by Benjamin Disraelis reforming ministry was the Artisans Dwelling Act which enabled local authorities to purchase and demolish slums and insanitary property; and a ground-breaking Public Health Act which compelled local authorities to ensure adequate drainage and sewage disposal, and to collect refuse on a regular basis. Later in 1875, another sign of progress Joseph Bazalgette completed his thirty-year construction of Londons sewers.

If we could magically go back in a time machine to the London of 1875, wed no doubt marvel at the new big thing in transport horse-drawn trams on rails, which since 1870 had been challenging the supremacy of the horse bus. Wed also be curious to see lamplighters, carrying long poles with wicks at the end to light the gas lamps which lit the citys streets, and public disinfectors clad in white coats, dragging handcarts into which they would put contaminated clothing and other materials.

Next page