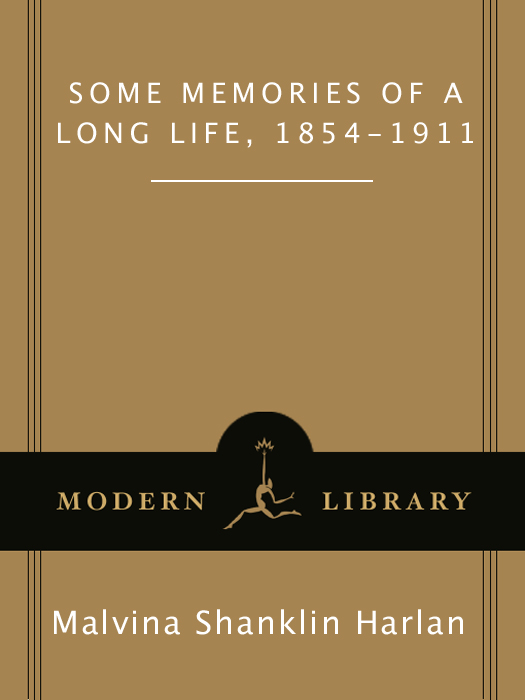

2002 Modern Library Edition

Copyright 2001 by Edith Harlan Powell, Eve Harlan Dillingham,

Elizabeth Derby Middione, John Harlan White, Peter Corning, and

Cynthia Corning Richardson

Foreword copyright 2002 by Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Epilogue copyright 2002 by Amelia Newcomb

Afterword and Notes copyright 2001 by Linda Przybyszewski

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright

Conventions. Published in the United States by Modern Library, a

division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in

Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

M ODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER Design are registered

trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This work was originally published in the Journal of Supreme Court

History, 2001, vol. 26, no. 1.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harlan, Malvina Shanklin, 18381916.

Some memories of a long life, 18541911/Malvina Shanklin Harlan;

foreword by Ruth Bader Ginsburg; introduction and notes by Linda

Przybyszewski.2002 Modern Library ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58836-251-3

1. Harlan, John Marshall, 18331911. 2. Harlan, Malvina Shanklin,

18381916. 3. Judges spousesUnited StatesBiography.

I. Przybyszewski, Linda. II. Title.

KF8745.H3 H37 2002

347.732634dc21

[B] 2001057959

Modern Library website address: www.modernlibrary.com

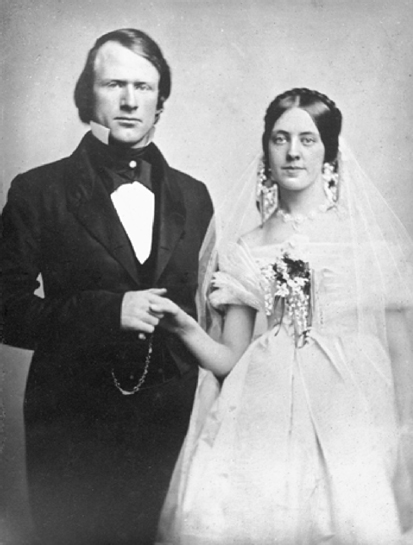

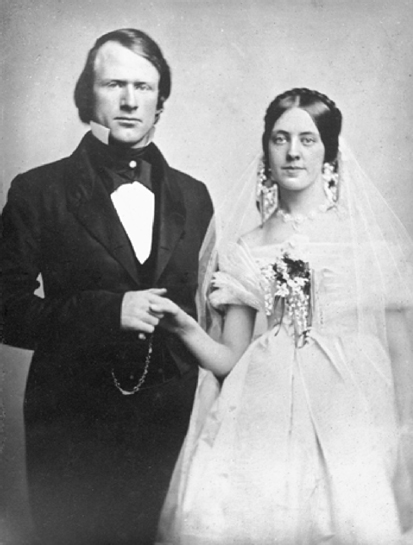

Frontispiece: John Marshall Harlan of Frankfort, Kentucky, and Malvina French

Shanklin of Evansville, Indiana, were married on December 23, 1856, after a

two-year engagement. The groom was twenty-three; the bride was seventeen.

v3.1

C ONTENTS

F OREWORD

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

The publication of Malvina Harlans Some Memories is cause for celebration.

The rooms and halls of the United States Supreme Court are filled with portraits and busts of great men. Taking a cue from Abigail Adams, I decided, when asked some years ago to present the Supreme Court Historical Societys Annual Lecture, it was time to remember the ladiesthe women associated with the Court in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Not as Justices, of course; no woman ever served in that capacity until President Reagans historic appointment of Sandra Day OConnor in 1981. But as the Justices partners in life, their wives.

Behind every great man stands a great woman, so the old saying goes. Yet one trying to tell the nineteenth-century wives stories runs up against a large hindrancethe dearth of preserved primary source material penned by the women themselves.

My law clerk, Laura W. Brill, and I began our research The Library of Congress aided that endeavor by furnishing us with a remarkable, yet unpublished manuscript written by Malvina Shanklin Harlan. Malvina was the wife of the first Justice John Harlan, who served on the Court from 1877 until 1911. Her manuscript was found among the Justices papers lodged at the Library. (Malvina lived from 1839 until 1916 but she dated Some Memories from 1854, the year she met John, until 1911, the year he died.) The manuscript, running some two hundred double-spaced typewritten pages, was edited by hand, and there were notations in margins, both perhaps in anticipation of a hoped-for publisher. Malvinas memoir is full of anecdotes and insights about the Harlan family; politics in Indiana, Kentucky, and Washington, D.C., in the pre and postCivil War period; religion; and, of course, the Supreme Court.

I was drawn to Malvinas Some Memories as a chronicle of the times, as seen by a brave woman of the era. Malvina wrote of her adjustment as a seventeen-year-old bride, when she left the free state of Indiana in 1856 to reside with John and his parents in Kentucky, and of her feelings when her mother-in-law presented her, on arrival, with a personal slave. She strove to serve her husband selflessly, yet did not surrender all pursuits of her own, particularly the music that brightened her life. The reader is drawn into the Hayes White House through Malvinas friendship with First Lady Lucy Hayes. We learn of the extraordinary encouragement Malvina gave to her husband when he wrote the lone dissent from the Supreme Courts judgment striking down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, a measure Congress enacted to promote equal treatment, without regard to race, in various public accommodations.

I thought others would find the manuscript as appealing as I did. For many months I tried to interest a university or commercial press in publishing Some Memories, to no avail. Ultimately, with my appreciation and applause, the Historical Society decided it would undertake the publication, and devoted the entire summer 2001 issue of the Societys Journal to Malvinas Some Memories. On the cover is a portrait of Malvina, age seventeen, and John, age twenty-three, on their wedding day.

In the Supreme Courts early-nineteenth-century days, when the great Chief Justice John Marshall led the Court, the Justices lived together in one boardinghouse or another when the Court was in session, leaving their wives at home. If the boardinghouses diminished family life, they served one notable purposethey helped to secure the institutional authority of the nascent, underfunded Supreme Court. Recent biographies of the great Chief Justice tell how John Marshall used the camaraderie of boardinghouse tables and common rooms to dispel dissent and achieve the one-voiced Opinion of the Court, which he usually composed and delivered himselfthe unanimity that helped the swordless Third Branch fend off attacks from the political branches.

Although Chief Justice Marshall strictly separated his court and family life, he did not lack affection for his wife. In a letter from Philadelphia in 1797, four years before his appointment to the Court, John Marshall told Polly of his longing. I like [the big city] well enough for a day or two, he wrote her. But then I begin to require a frugal repast with cool water. I wou[l]d give a great deal to dine with you today on a piece of cold meat with our boys beside us & to see little Mary running backwards & forwards over the floor.

In 1832, a year after Pollys death, Marshall reflected: Her judgement was so sound & so safe that I have often relied upon it in situations of some perplexity. I do not recall ever to have regretted the adoption of her opinion. I have sometimes regretted its rejection.

Sadly, Polly Marshalls letters to her husband did not survive history, but we have Malvina Harlans vivid record of the relationship of another Supreme Court Justice and his wife in her Some Memories.

In commenting on her decision to marry John, a slave-owning Kentuckian, Malvina, who lived her first seventeen years in Indiana, wrote:

All my kindred were strongly opposed to Slavery, the peculiar institution of the South. Indeed, an uncle on my mothers side, with whom I was a great favorite, was such an out-and-out Abolitionist that I think (before he came to know my husband) he would rather have seen me in my grave than have me marry a Southern man and go to live in the South.

On her husbands decision to join the Union Army five years after their marriage, when two children were part of the family, Malvina recalled: