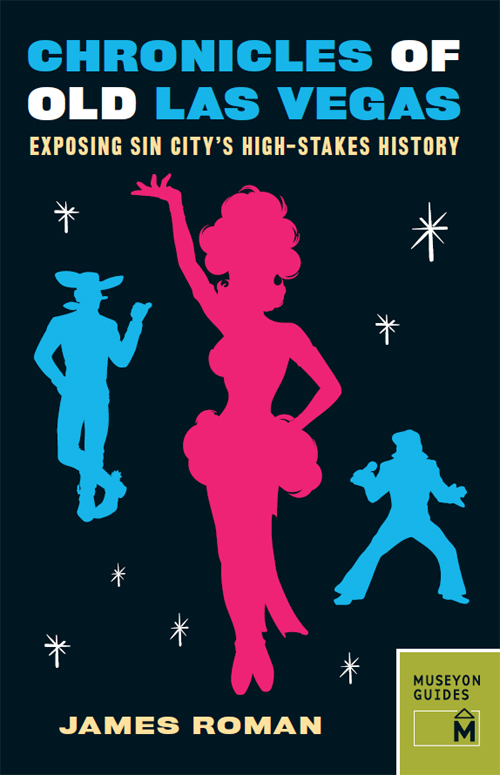

20112012 James Roman

Published in the United States by:

Museyon, Inc.

20 E. 46th St., Ste. 1400

New York, NY 10017

Museyon is a registered trademark.

Visit us online at www.museyon.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for the purpose of review, and no part of this publication may be sold or hired without the express permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-9846334-1-8

71901959

To Jim Scarpace, who showed me the best parts of Las Vegas.

CHRONICLES OF OLD LAS VEGAS

CHAPTER 1.

THE SPRING

It started as an oasis.

Picture a grassy meadow surrounded by an inhospitable desert. For millennia, that was the place we now call Las Vegas. Almost miraculously, over an expanse nearly 40 miles long and 15 miles wide, a spring bubbled up through the Mojave Desert floor. Its fresh water supported plant and animal life, and the indigenous Paiute tribe.

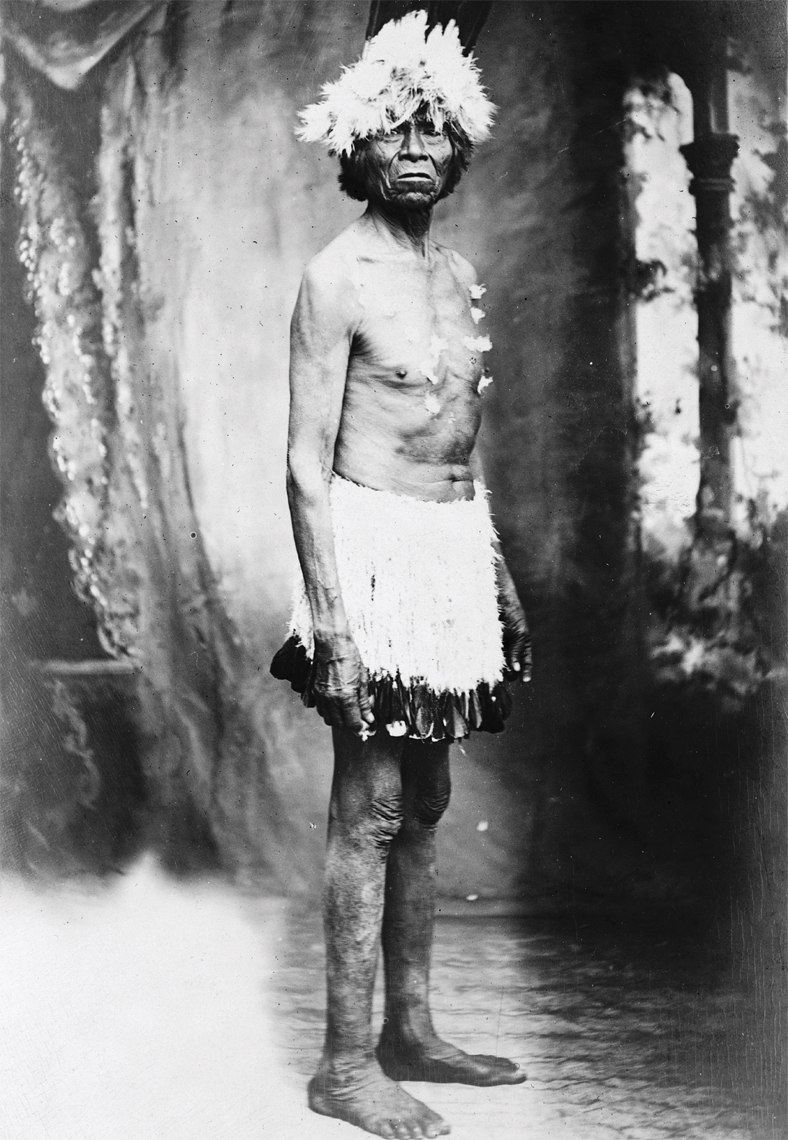

Captian John, a Paiute Indian, circa 1903

The Paiute believed the earth to be sacred. Though they had no private property rights, they were protective of their spring; it was Paiute ancestral land for as many as 4,000 years. When the white mans culture eventually encroached, it was Chief Tecopa, the final leader entrusted to protect the spring, who gave up the indigenous peoples sacred oasis peacefully.

The Paiute didnt know that, for 300 years starting in 1521, Europeans had called their grassy meadow New Spain. And in 1776, when missionaries blazed a path between New Mexico and California called the Old Spanish Trail, the Paiute had no idea.

These indigenous people were nomads who spoke a language similar to the ancient Aztecs. In winter, they wore coats made from rabbit pelts, and when the weather got hot, the Paiute went nearly naked. Five to 10 families would roam together as a group, perhaps as many as 100 people. In the winter, all tribes-members would gather in one or two semi-permanent settlements. Then in the spring, they would scatter again in their nomadic quests for food and adventure.

Meanwhile, merchants and missionaries crisscrossed the territory along the L-shaped Old Spanish Trail. It was the easiest but not the most direct route to Los Angeles; some explorers continued to search for a shorter way. In November 1829, a team of 60 Spanish merchants led by the explorer and trader Antonio Armijo strayed from the trail. Their scout, Rafael Rivera, discovered the verdant oasis that he proclaimed Las Vegas, the meadows in Spanish. Armijos traders were the first Europeans to behold the unexpected oasis.

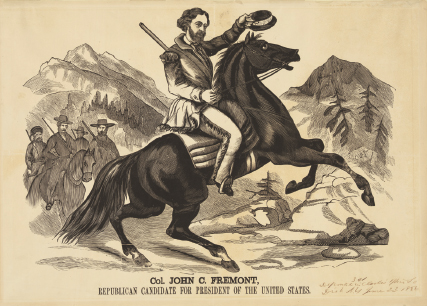

In 1844, John C. Frmont, adventurer and son-in-law of a prominent U.S. Senator, surveyed the Nevada Territory with Kit Carson as his guide. During a five-month journey with 25 men, Frmonts cartographers mapped the springs territory in detail. Frmont wrote: Two narrow streams of water, four or five feet deep, gush suddenly, with a quick current, from two singularly large springsthe taste of the water is good but rather too warm to be agreeable.

The Paiute attacked the intruders. Chief Tecopa and his warriors attempted to chase Carson and Frmont away from the spring, grossly underestimating the foe they had encountered. A three-day skirmish ensued; Carson subdued the Paiute with the crack of his pistol, a sound heard at the spring for the first time. Tecopa soon reversed himself, serving as a crucial intermediary between two cultures. However, following this first encounter, Frmont cast a harsh eye on the indigenous hunter-gatherers, writing that the Paiute he observed were humanity in its lowest form and most elementary state.

An undated photograph of Della Fisk and Chief Tecopa, Pahrump Valley, Nevada

Despite the altercation with the Paiute, when Congress published Frmonts report, settlers had one more reason to head west. And, when President Lincoln proclaimed Nevada as Americas 36th state on October 31, 1864, a metamorphosis at the Las Vegas springs was inevitable. Tecopa realized that the Paiute must adapt or die.

With the arrival of white settlers, the indigenous people were soon embroiled in conflicts over land ownership and the produce from fields that were irrigated by the spring. Chief Tecopa, just two years younger than Frmont, represented the final generation of nomads.

Paiute Indian group posed in front of adobe house, circa 1909-1932

Though his name meant Wildcat, Tecopa kept it peaceful. He displayed his willingness to accommodate the white settlers by wearing his best European attire and was frequently seen in a silk top hat and a red marching-band jacket with gold braid. Elsewhere in America, native people were being herded off the land and slaughtered along the Trail of Tears, but not so at the springs in Tecopas Las Vegas. He encouraged a bloodless assimilation for the Paiute, leading them to work for wages in white culture, as laborers in the mines and as domestic helpers on the ranches. Ten percent of the Paiute population died of typhoid or other European diseases to which they had no immunity. Many others suffered psychological shock, witnesses to the end of nomadic life in North America.

One of the first settlers to own a piece of the meadow was Octavius Decatur Gass from Ohio, who eventually expanded his holdings to 640 acres. He hired Paiute workers to harvest his wheat, oats and barley. After the first harvest, they planted fruits and vegetables too. Other landowners followed. The transfer of the oasis was complete; pioneers mixed with native people to create the first permanent settlement in the valley.

Colonel John C. Frmont, 1856

Tecopa lived to see his people into the 20th century; he died in 1904, buried with his son and grandson at the Chief Tecopa Cemetery in Pahrump Valley, Nevada. In 1971, Nevada Governor Mike OCallaghan dedicated a state memorial to the Chief at his gravesite.

Meanwhile, Frmont became the new Republican Partys first candidate for U.S. President. (He lost to one-term Democrat James Buchanan.) He later became the Governor of the Arizona Territory. Today, counties in four states, and the central boulevard in downtown Las Vegas, are named for him.