CHRISTINE DE PIZAN

Covering one of the most fascinating yet misunderstood periods in history, the MEDIEVAL LIVES series presents medieval people, concepts and events, drawing on political and social history, philosophy, material culture (art, architecture and archaeology) and the history of science. These books are global and wide-ranging in scope, encompassing both Western and non-Western subjects, and span the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, tracing significant developments from the collapse of the Roman Empire onwards.

SERIES EDITOR: Deirdre Jackson

Christine de Pizan: Life, Work, Legacy Charlotte Cooper-Davis

Margery Kempe: A Mixed Life Anthony Bale

CHRISTINE DE PIZAN

Life, Work, Legacy

CHARLOTTE COOPER-DAVIS

REAKTION BOOKS

For dad, in memoriam

and for Alistair, in anticipation

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright Charlotte Cooper-Davis 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789144413

CONTENTS

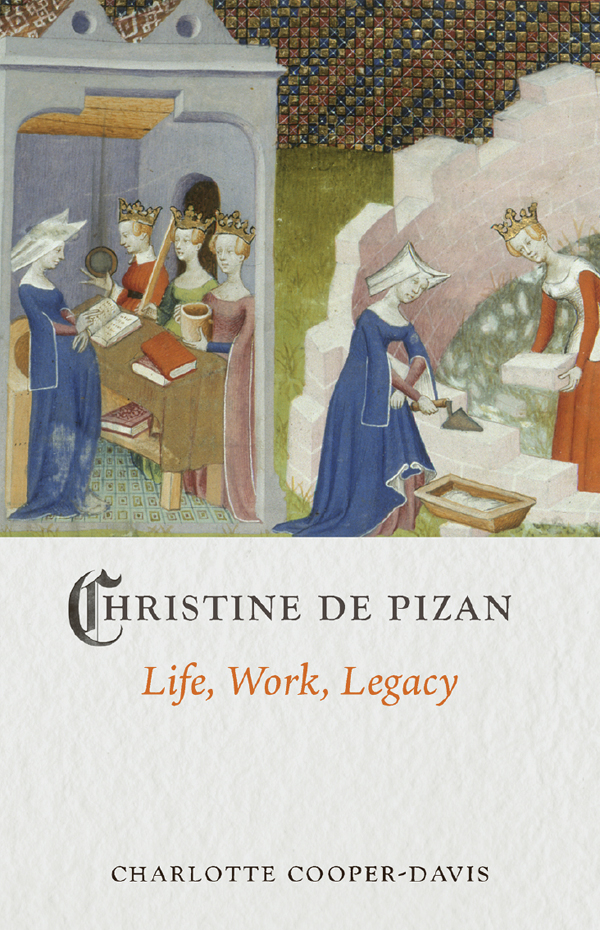

Miniature of Fortune spinning her wheel, taking some men down and making others greater, from Collected Works (The Book of the Queen), c. 141014.

Introduction

Oh... you have done me a great favor by taking me to Long Study, for I am fated to practice it for my entire life.

Le Livre du chemin de long estude

F ew medieval writers were as prolific as Christine de Pizan. Over a career that spanned almost four decades, she composed around thirty major works as well as several shorter poems. These survive in over two hundred manuscripts an extraordinary figure for an individual medieval author. For comparison, just a single manuscript exists of the Old English epic poem Beowulf and even Chaucers Canterbury Tales, which were being composed around the time that Christine was writing, survive in only 32 copies. What is even more remarkable in Christines case is that she oversaw the production of 54 of her manuscripts herself and several of them are written in her own hand. It is not known how many further copies of her works are likely to have been lost over the centuries.

Such an enormous literary production would not have been possible had its executor not been deeply familiar with contemporary culture and compositional practices. For her works to circulate, a pragmatic knowledge of writing, bookmaking and booktrading was required; for them to be popular, they needed to display a mastery of popular and fashionable poetic themes, which would also secure her valuable patronage from some of the highest-ranking nobles of the time. Gaining the dexterity required to be proficient in these various areas was no easy task in the Middle Ages especially for a woman without a clerical education so despite her prolific output, Christine did not turn to writing until relatively late in life. Before she was to take up her pen, her life was to undergo a series of twists and turns that would set her on the path to becoming an author.

Christine was born in Venice around 1364, but she only spent a short amount of time in that city. Her father, Thomas de Pizan Thomasso de Benvenuto da Pizzano, to give him his full Italian name was appointed astrologer to the French court in Paris shortly before 1368. Once he had settled in the city, he sent for his family to join him. It was through her father and his position that Christine first became embedded in the literary and scholastic culture of the late European Middle Ages. When she was born, Thomas was a lecturer at the prestigious Italian University of Bologna, which he had also attended as a student and where he was a contemporary of the poet and scholar Petrarch. The education that he received would have been second to none. He trained to become a doctor in medical studies, which required studying the arts along with astrology and natural philosophy, mathematics, logic and rhetoric.

A love of learning ran in the family. This was probably what drew Thomas to accept the position at the French court, which was famous for its intellectual culture (he turned down a similar role he had been offered at the court of Hungary when forced to choose between the two). King Charles V of France, who came to the throne around the same time that Christine was born, was a monarch committed to learning. He had recently embarked upon a huge enterprise, known as his Sapientia (meaning knowledge) project, which involved investing heavily in new books that would be housed in a sumptuous new library in the Louvre. To do so, he commissioned numerous writers and artisans to fill his shelves with new works these were not only literary works, but testaments to the various forms of cultural and artistic practices that were thriving in Paris at the time. Charles VS project did not just require authors and scribes to compose and copy the texts, but the work of translators, illuminators and artists, bookmakers, carpenters and metalworkers, architects and designers. Meanwhile, the flourishing University of Paris (of which Charles was a patron) continued to attract leading scholars to the city, many of whom went on to take up positions at the royal court. Through her fathers work, Christine would get to know many of the people who carried out these duties in a personal capacity.

This thriving intellectual and artistic atmosphere formed the backdrop to Christines youth. Without the benefit of such a rich cultural background or her fathers connections, she might not have had access to the materials that enabled her career as a writer to take shape. Yet, although she undoubtedly enjoyed a period of great happiness, the circumstances that led her to take on this role are hardly enviable.

At Fortunes Mercy

When she was fifteen years old, Christine married a royal secretary named Etienne de Castel, who was about ten years her senior. Like her father, Etienne was university-educated, and Christine describes her admiration for his great learning in similar terms to those she expresses for her father. Although her husband was chosen by Thomas, there is no reason to believe the union was anything but happy. Christine herself concedes that truly... I would not have essayed to choose better by my own wishes. She and Etienne had three children together, two of whom survived. One of them, Jean de Castel, also went on to have a career as a writer. The decade of Christines life during which she was married was a happy and prosperous time for her and her family.

Alas, it was not to last. Between 1380 and 1390 Christine was dealt a series of blows, starting with the death of Charles V, who as employer to both her husband and father was her familys main protector. Etienne and Thomass financial situations both suffered as a result. In Le Livre de lavision Cristine