In memory of my father, J. Everett McCracken

If your husband has you seething

Belladonna you must feed him

Add some pepper, make it pleasing

Hell be laid out by the evening.

lyrics to a Hungarian folk song

Nagyrv lies in an angle formed by the bending of the Tisza River, therefore in a little valley about fourteen miles square. It looks a quaint, Old World village where it sprawls by the river side, its low white cottages encircled by gardens. It is twenty-five miles from the nearest railway station.

Budapest, which is puzzled and shamed by the discovery of this plague spot in the midst of a smiling countryside not sixty miles from its own doors, has sent many newspapermen and other investigators to discover the conditions which produced it. They found [a village] inhabited by poor farmers, dependent for existence on farms and vineyards already small and ever newly divided as sons succeeded fathers; the whole ringed round as by an iron girdle with huge estates. Growth has been impossible, young people have been denied both land and opportunity, and by the same vicious process children have been transformed from a blessing into a curse.... But this field which culture had allowed to lie fallow proved fruitful for [Auntie Suzy].

The name [Nagyrv] has spread through the whole world. The notoriety has made all Hungary uncomfortable. It has been bad propaganda abroad. It has been a shock at home to find, within sixty miles of the capital, a neighborhood which might better belong to the darkest period of the Middle Ages.

It makes a strange tale in 1930.

J OHN J ACK M AC C ORMAC,

V IENNA B UREAU C HIEF, N EW Y ORK T IMES , M ARCH 1930

Contents

Most first names have been anglicized, and some surnames have been, as well. Some first names have been changed for clarity, as many of the people portrayed had the same name. Some street names have also been anglicized. The names of historical and political figures who do not figure prominently have been left in their original Hungarian form.

This is a true story. All events happened as recorded here, or as I believe them to have happened, based on years of research, interviews, trial transcripts, and piecing together the volumes of archival data.

However, to fill in gaps, I have had to imagine or assume certain scenarios. Ive done this with deep respect for the integrity of this case.

Any dialogue in quotes was taken directly from archival materials.

Kis Hrlap , a Budapest newspaper, ran a photo spread of the investigation. From top left: Curious onlookers, who flocked in from other Plains villages, peer into the graveyard caretakers hut in Nagyrv to watch an autopsy being performed; prosecuting attorney John Kronberg; portrait of Auntie Suzy, date unknown; gendarmes in the graveyard; Auntie Suzys pantry; gendarmes round up suspects in Nagyrv.

Collection of Attila Tokai

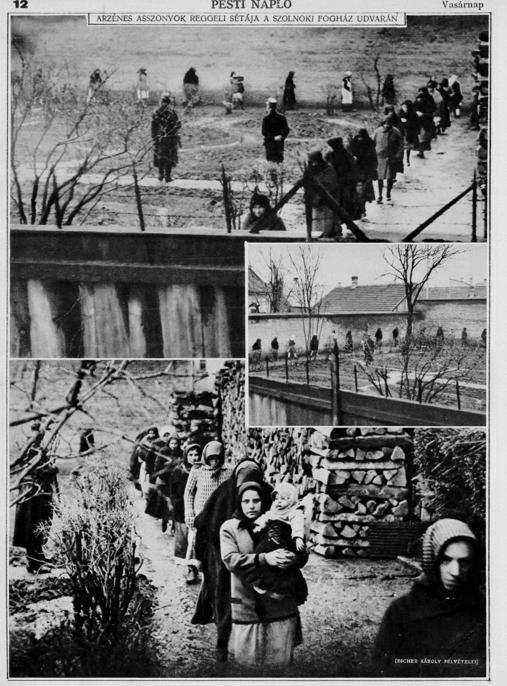

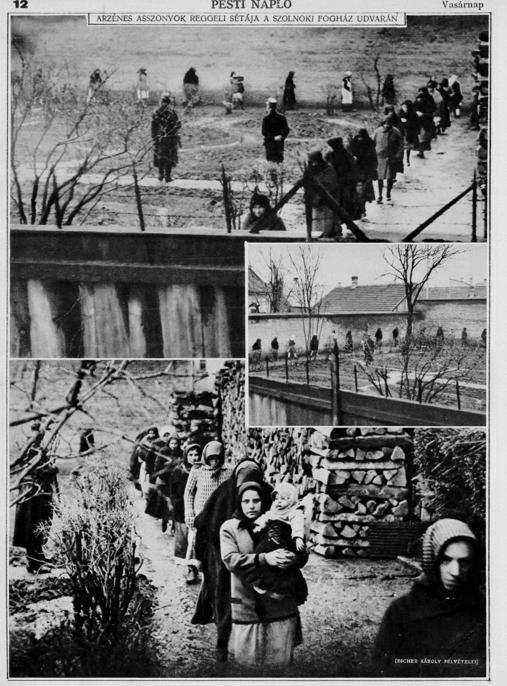

The family of M. W. Mike Fodor and Elizabeth de Pnksti owned the Pesti Napl newspaper in Budapest, which ran this photo spread of what came to be known as The Arsenic Trials. The women exercise in the prison yard while guards keep watch.

Collection of Attila Tokai

The boldness and utter callousness with which they carried on their criminal activities seems to have been equaled only by the stupidity of the men who were their victims, the husbands and fathers who saw friend after friend die in the same sudden agonies without ever divining a secret which seems to have been known or suspected by nearly every woman in [Nagyrv]. J ACK M AC C ORMAC, N EW Y ORK T IMES

Wednesday, August 16, 1916

Anna Cser lay on the floor of her living room.

Her back was red and crawling with an itch. She had been lying for hours on the sackcloth the midwife had laid out for her, and the burlap had left a platoon of faint crosshatches imprinted on her skin. Maddening bits of the flax were clinging to her. She was cloaked in a thick hide of summer sweat, and all the impossible bits of filth she had failed to clean from the room had floated to her, freckling her with speckles of dirt and dust.

Her stringy brown hair hung wet around her neck and shoulders. She took quick swipes at her forehead to push the strands from her brow, but they soon found their place again and plunked big stinging droplets of sweat into her eyes, which rolled down her face as tears.

Anna gasped. She gripped the sackcloth with both hands and pulled herself up on her haunches. Pain ripped through her. She could hear herself shrieking at it, and she could hear the midwife shouting hoarse instructions over her.

She guided a breath up slowly, carefully, around the edges of the pain, and concentrated hard on the midwifes words. She had done this before, Anna reminded herself, and she could do it again.

She soon felt the midwifes hands on her belly. Auntie Suzy had placed a warm, wet cloth across her abdomen, and now pressed it to her gently. A faint smell of cooking oil rose off the compress, part of an elixir that the midwife used to soothe muscles.

The pain slowly dissolved. Anna lay back breathless on the sackcloth. Her legs shook with exhaustion. The palms of her hands burned where she had clenched the burlap too tightly.

Anna was small for a Plains woman. Had she been beautiful, others might have viewed her as petite, but Anna was all knobby bones and reedy muscles, a haphazard geometry of hard angles that had her moving through the world as if bumping into it.

Her skin was nearly translucent. Her thin blue veins were like stained glass, as she had not a lick of fat on her. She was as spindly and rawboned now as shed always been, except for her pregnant belly.

Auntie Suzy had been with Anna for most of the afternoon. She circled around her, padding heavily in bare feet across the cool, earthen floor. She had left her boots on the porch when she had arrived earlier in the day with Annas husband, Lewis, whom she had not seen since. She wondered and worried where he had gone.

Auntie Suzy wore, as ever, a black dress with an apron fastened over it. In her apron pockets, she kept her essentials. One held her corncob pipe and a small pouch of her favorite tobacco, along with a case of striking matches. In the other was a glass vial filled with her solution, capped with a wooden stopper and concealed in white paper.

She considered her solution one of her greatest magics.

The midwife ferreted in her pocket and withdrew her pipe. She lit it and took a long, studied draw as she considered the possibilities. Lewis never went far. She thought he could be in the shed, or perhaps he was still at the bar. The midwife exhaled a small, ghostly cloud of white smoke, which curled out of her mouth and hung briefly in the air in front of her before dissolving. Where was Lewis? That was the question.

The living room depressed Auntie Suzy. It was small and the ceiling was so low she could nearly touch it with her chubby hand. The walls were bare, except for a few Catholic icons fitted inside homemade frames. They hung loosely from pegs with the rough twine Anna had taken from the shed. The Catholics were an unenviable lot in Nagyrv, the midwife thought, the poorest of the poor, and landless, like Anna.

A battered credenza leaned crookedly against the far wall. A ragged towel hung from a peg, as did a calendar, given out free by the village council. There was a mishmash of items arranged on the floor and table: an old wooden pail that Anna used to fetch water from the well, a step stool, a few bowls, some of them cracked and chipped, and a paraffin lamp, for which Anna never seemed to have oil. There was a single wooden bench to sit onnothing more. In the evening, Anna slept in the room with the children on straw mats they rolled out. Sometimes Lewis came in from the bar and passed out there, filling the room with his rasping snores.

Next page