Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

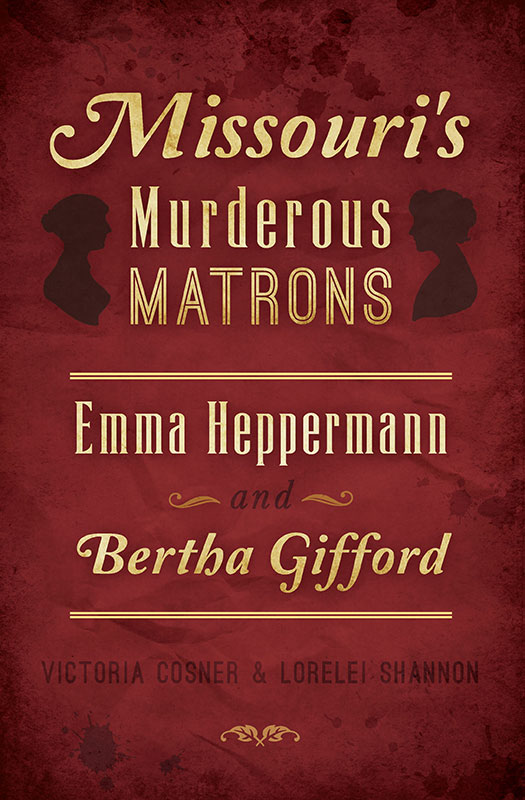

Copyright 2019 by Victoria Cosner and Lorelei Shannon

All rights reserved

First published 2019

E-Book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.628.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018963519

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.072.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my two daughters who put up with this hobby.

(Victoria)

To Victoria, for taking me with her on this amazing journey.

And to Sir, with love.

(Lorelei)

Contents

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the stranger who walked into my historic site and asked about the woman who poisoned all those people in St. Peters and started us on this journey. Thank you to Marc Houseman, Washington Historical Society, for showing me your incredible collection on Bertha; Dawn from the Morse Mill Hotel; Dawn Frederickson from Missouri State Parks, who provided guidance on finding some of the sites; Charles Brown of the Missouri Mercantile Museum; and Jim Karase for help on law enforcement concepts. And a huge thank-you to Andrea Kundrath, Suzanne Lane and Mommy Fran for editing and moral support.

Introduction to Two Murderesses

The gods have sent medicines for the venom of serpents, but there is no medicine for a bad woman. She is more noxious than the viper, or than fire itself.

Euripides

When people think of the Missouri of the past, they often think of bucolic farmlands as far as the eye can see; a landscape of green and gold dotted with charming farmhouses and sparkling ponds. This is the land of Tom Sawyer, where fish await catching in gurgling creeks and winding rivers. Woods and caverns beg to be explored by adventurous children. Men protect and provide for their families, but women are the heartbeat of the household. This is a wholesome place, the heart of small-town America. People were generally seen as being honest in Missouriopen, plain folks who worked the land and looked out for their neighbors.

In early twentieth-century Missouri, small-town America was everywhere. Tucked into hills, hollows and bends in the river were little communities that hummed with life. Main streets, where you could buy groceries and hardware at the general store and catch up on the latest gossip, were busy. Some folks lived in town, some on farms. During the day, farm families would pour in, selling their produce and stocking up on supplies. Townie or farm boy, everybody knew each other in these small Missouri towns, for better or worse. But sometimes, the townspeople did not know someone as well as they thought they did.

Sometimes there were secrets. Some were ordinary secretsbabies born too soon after the wedding, families struggling with debt, the unhinged uncle who always made a scene when he drank too much. But there were darker secrets. People who appeared to their friends and neighbors to be friendly, helpful members of the community. People who were trusted, even loved and relied upon. People whose secrets were more than scandalous; they were dangerous. Deadly.

In two small towns in rural Missouri, towns that appeared to be just like all the others, something was very wrong. People kept dying. The deaths were centered on two women, respectable matrons both. Bad luck and sorrow followed these women wherever they went. Loss was at the center of their lives. So much loss.

Early on the morning of August 25, 1928, fifty-three-year-old housewife Bertha Gifford was arrested at her new home outside of Eureka, Missouri. Bertha had fancied herself to be a nurse for the local community of Catawissa, fifteen miles from Eureka. But she had no medical training and a horrifyingly high mortality rate. Stories had been circulating for some time about the people whom Bertha took to her farmhouse to nurse back to health, about the ones who never got better and left the Gifford house in a pine box, about how many times the coroner wrote acute gastritis on death certificates. As many as seventeen souls in her care never recovered. To put a finer point on it, up to seventeen people in the care of Bertha Gifford died horrible, painful deaths as she watched their every agonized spasm and cry.

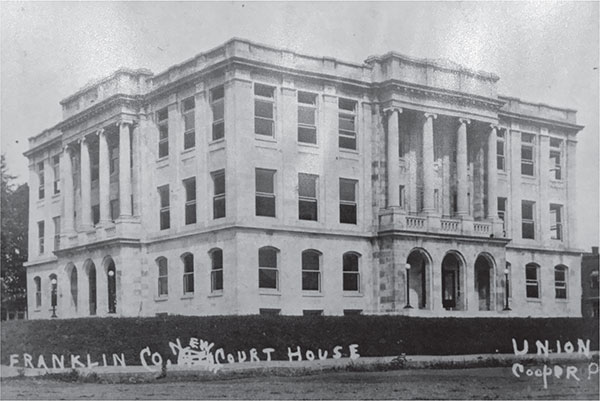

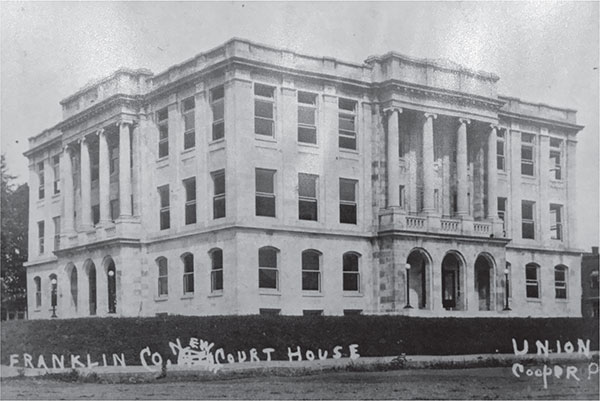

Emma Stinnett lived in the small town of Steelville, about fifty-six miles from Bertha Gifford. In 1928, when newspaper accounts of Bertha Giffords arrest flooded Missouri, Emma had just gotten started; her husband, Charles, died on July 15, 1925. Emma had bad luck with husbandsthey just kept dying on her. She would lose five (six if you count the one who disappeared) of seven husbands in the coming years. Emma also had bad luck with the families of her husbands, who had a habit of falling horribly ill and sometimes dying. Years apart, both of these women would eventually end up at the Union, Missouri courthouse on trial for murder.

Between these two women, they killed more than twenty people. Friends, relatives and neighbors were not safe. Nobody was. Bertha alone killed about 10 percent of the population of her small town of Catawissa for inexplicable reasons that may have amounted to nothing more than her own amusement. Emma used her husbands, mostly hardworking, honest men, as disposable sources of quick cash. But neither Bertha nor Emma was suspected for the longest time. In some ways, the early twentieth century was a more innocent, or at least trusting, time. The evidence of foul play was glaringly obvious by the time Berthas and Emmas neighbors finally started whispering their suspicions.

New Franklin County Courthouse. Courtesy of Franklin County. Authors collection.

When at last Bertha and Emma were arrested, town elders exchanged knowing looks and nodded solemnly. When poison is involved, they said, it is always a woman who did the crime. (Well, not always. More on that later.)

Poisoning is viewed as a passive, nonviolent method of murder. But domestic poisoning is stunningly cold-blooded and cruel. How hard-hearted must a person be to give that initial dose, watch the victim grow ill and then sit by the bed of their loved one, whispering comfort and spoon feeding them death? What kind of a person spends days, weeks, even months slowly murdering the people who trust them?

Human monsters are rarely frightening to the eye. Photographs and contemporary accounts of Bertha and Emma describe women of an efficient, matronly demeanor. Whatever horrors may have lurked in their hearts, they did not show on their faces. They both wore the facade of respectable women, the kind of sturdy Midwestern matriarchs who were the pillars of their families, the hearts of their households. They were both good cooks. Very good cooks. Bertha was known for her biscuits. Emma made potato soup to die for. But both of them used a special secret ingredient: arsenic.

Next page