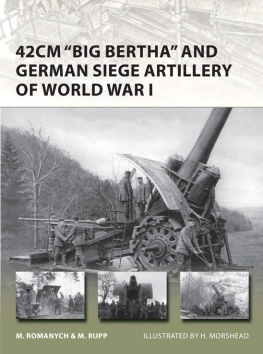

NEW VANGUARD 205

42CM BIG BERTHA AND GERMAN SIEGE ARTILLERY OF WORLD WAR I

| M. ROMANYCH & M. RUPP | ILLUSTRATED BY H. MORSHEAD |

CONTENTS

42CM BIG BERTHA AND GERMAN SIEGE ARTILLERY OF WORLD WAR I

INTRODUCTION

In the first days of World War I, Germany unveiled a secret weapon the mobile 42cm (16.5 inch) M-Gert howitzer. At the outbreak of the war, two prototype guns were rushed from the factory where they were still undergoing pre-production modifications to the Belgian fortress of Lige. There, they handily demolished two of the forts; one of which Loncin blew up in a catastrophic explosion, effectively ending the siege. Jubilant, German soldiers christened the guns Dicke Berta (Big or Fat Bertha), possibly after Bertha von Krupp, owner of the firm that built the howitzers. Soon after, German newspapers picked up on the nickname and the legend of Big Bertha was born.

Shrouded in secrecy, the existence of mobile 42cm howitzers came as a shocking surprise to the Allied Armies. After Lige fell, wild rumors circulated about the guns, and the name Big Bertha was commonly used to refer to any large-calibre German artillery piece. Misinformation flourished and the mythology of Big Bertha grew, spawning several falsehoods that live on to this day in English-language histories of the war.

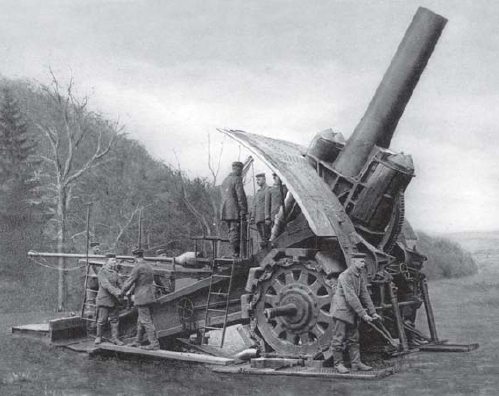

At the wars start, the German Army had only two prototype 42cm M-Gert Big Bertha howitzers, both of which were undergoing pre-production modifications. The spoke wheel of the howitzer in this German propaganda photograph indicates that it is one of the prototype guns. (M. Romanych)

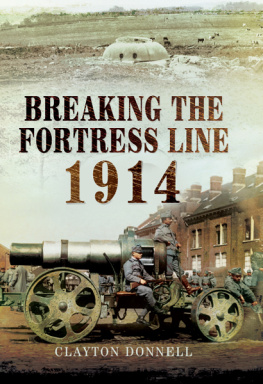

A battery of 21cm howitzers prepared for action. Both Belgium and France designed their fortifications to withstand hits by 21cm projectiles, not realizing that the German Army would develop larger caliber mobile siege guns. (M. Romanych)

FORTIFICATIONS VERSUS ARTILLERY

During the last half of the 19th century, advances in artillery technology and design prompted an arms race between artillery manufacturers and fortification engineers. Introduction of breechblocks, recoil mechanisms, and rifled barrels led to a new generation of field guns and howitzers with greatly improved range and accuracy. In response, military engineers completely redesigned permanent fortifications, abandoning large, star-shaped Vauban-style bastioned forts in favor of smaller, polygon-shaped forts. Depending on terrain, these forts were often grouped together into ring-fortresses and fortified barriers. Ring-fortresses consisted of several forts arranged in a circle around a city at a distance sufficient to keep enemy artillery out of range of the city (typically about 12 kilometers). Fortified barriers were groups of forts either clustered together to secure a strategic point or arrayed in a line to block an invasion route. In France, ring-fortresses and fortified barriers were combined to create expansive fortification zones.

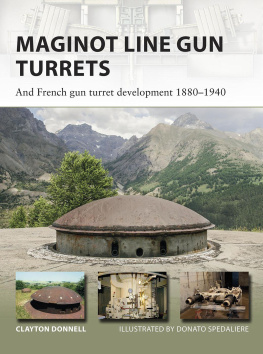

A second technological advance was the replacement of black powder with more powerful high-explosive propellants and bursting charges. This development led to a new generation of shells equipped with delay fuses that multiplied heavy artillerys firepower against fortifications. Fielding of these improved munitions prompted another round of fortress construction. Fortress engineers hardened existing fortifications by reinforcing or replacing masonry with concrete, covering portions of the forts with earth, adding underground galleries and shelters, and relocating artillery from open ramparts into armored casemates and rotating steel turrets. Completely new fortifications were also designed and built. These so-called armored fortifications resembled land-locked battleships and were essentially large fortified artillery batteries purposely designed to defend against artillery bombardment rather than infantry assault.

By the turn of the 20th century, the borders shared by France, Belgium, and Germany were heavily fortified. Frances fortifications were by far the most extensive with ring-fortresses at Lille, Maubeuge, Verdun, Toul, Epinal, and Belfort connected by barrier forts into several fortress zones. The capital, Paris, was a fortress protected by a double ring of 41 forts. Likewise, Belgium had ring-fortresses at Lige and Namur, and Antwerp was turned into a national redoubt surrounded by some 50 forts and other smaller fortifications arranged in two concentric rings. For its defense, Germany had two modern fortress zones: one around Metz and Thionville in Alsace and another at Strasbourg in Lorraine. Older fortifications guarded Rhine River crossings at Wesel, Cologne (Kln), Koblenz, Mainz, Germersheim, Neu Breisach, and Istein.

Eastern Europe was also well fortified. Germany had fortified zones in East Prussia at Knigsberg (Kaliningrad) and Ltzen (Giycko) and a series of ring-fortresses along the Vistula, Warthe, and Oder rivers at Danzig (Gdask), Marienburg (Malbork), Graudenz (Grudzidz), Thorn (Toru), Posen (Pozna), Kstrin (Kostrzyn), Glogau (Gogw), and Breslau (Wrocaw). Germanys ally, Austria-Hungary, fortified its border with Russia with ring-fortresses at Cracow, Przemyl, and Lemberg (Lvov). Its border with Italy was defended by a line of barrier forts in the Alps. Russia maintained large ring-fortresses in Lithuania at Kovno (Kaunas) and Grodno, and in Poland at Osowiec, Novogeorgievsk (Modlin), Warsaw, and Ivangorod and a number of barrier forts in between the fortresses to block river crossings. Deeper inside Russia were fortresses at the strategic points of Dvinsk (Daugavpils) and Brest-Litovsk.

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

After winning the Franco-Prussian War, the German Army dismissed the utility of heavy artillery, even though heavy guns had successfully reduced French forts during the sieges of Metz, Strasbourg, and Toul. So strong was the sentiment, that artillery was separated into two branches the Feldartillerie (field artillery) with mobile, light field cannons and the Fuartillerie (foot artillery) with heavy mortar and howitzer pieces. Priority was given to the field artillery while foot artillery was allowed to languish.

Priorities changed in the 1880s, when Chief of the General Staff Generalfeldmarschall von Moltke demanded an artillery solution to what he termed the fortress dilemma. As he saw it, new permanent fortifications built by France, Belgium, and Russia were hemming in Germany. In a future war, Germany would have to attack and destroy these fortifications. However, the armys largest artillery pieces were the foot artillerys aging 15cm and 21cm pieces, which could not destroy modernized French and Belgian fortifications; hence the dilemma.

The situation grew serious for Germany when France and Russia signed a military alliance in 1893. This meant that in the event of war, the German Army would likely fight both countries simultaneously. In response to the possibility of a two-front war, new Chief of the General Staff, Generalfeldmarschall von Schlieffen, developed a strategy to defend against Russia while attacking France. A key and unsolved component of his plan was the quick reduction of fortifications that blocked invasion routes into France. Lacking any means to destroy the fortifications, the General Staff turned its attention to large-caliber siege artillery as a solution.