First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

P E N & S W O R D M I L I T A R Y

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

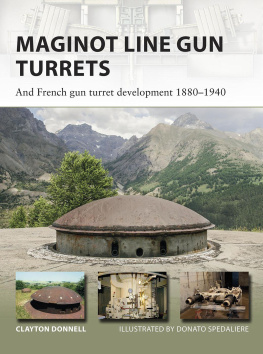

Copyright Clayton Donnell, 2013

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-84884-813-9

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47383-128-5

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47383-012-7

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47383-070-7

The right of Clayton Donnell to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD4 5JL.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology,

Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime,

Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime,

and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

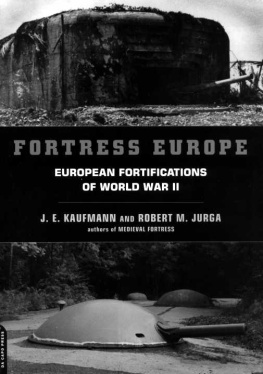

I would like to thank the following people, without whom this work would have been, if not impossible to accomplish, much more difficult. My brother Jim, first of all, helped me with editing and with ideas, and offered a lot of moral support over the last eighteen months. Marc Romanych, an expert in German heavy siege guns, helped me with research on that subject and helped set the record straight on the many myths surrounding the use of the heavy guns, plus Marc provided me with several great photographs from his collection. My daughter Erin Joyner was a great help with creating the maps and making the photos look as good as they could be. The Muse du Gnie at Jambes, Belgium, especially Yves Deraymaeker and Vincent Scarniet, helped me considerably with information about the fortified position of Namur; Vincent spent hours photographing, scanning and researching material for the book. Franois Hoff, a long-time friend and fortifications colleague, provided me with some information and photographs. Thanks to Jean Denis of the Association Hommage au Combattant du Fort Haxo (Fort de Manonviller) for several great photographs, maps and personal documents written by the garrison of the fort. Mark Berhow, Karl Fritz and Terry McGovern, from the Coastal Defense Study Group (CDSG), assisted me with research on the use of Gruson armoured turrets in the United States. Jean-Yves Mary, writer of the excellent series on the Maginot Line and a longtime expert on that subject, provided me with valuable information on the fortress of Longwy. The Centre Ligois dHistoire et dArchitecture Militarie (CLHAM), from Lige, provided several photos. Thanks to Joe Kaufman for recommending me to the editor. Finally, to my wife Donna, who put up with my absence for the past year to prepare this book and for providing me feedback that boosted my confidence about the work.

Chapter One

An Introduction

The first International Exhibition was held in Londons Crystal Palace in 1851 and was meant to showcase science and technology from countries around the world. Arthur Goodrich, in The Worlds Work, written in 1902, commented, The general lessons of the mechanical exhibits are these that machinery is making rapidly what hands used to make slowly; that electricity instead of steam is operating machinery, and that faster trains and boats, together with new electrical inventions, are constantly increasing channels of communication.

The Great Exhibition, as it was called, featured Frederick Blakewells facsimile machine, Mathew Bradys daguerreotypes and a number of revolvers manufactured by Colt. The exposition returned to London in 1862 and displayed naval engines, the first household gadgets and an exhibition of the Bessemer process for manufacturing steel from molten pig-iron. These new inventions were viewed by millions of visitors and brought about the realization of how the world was changing in the second half of the nineteenth century.

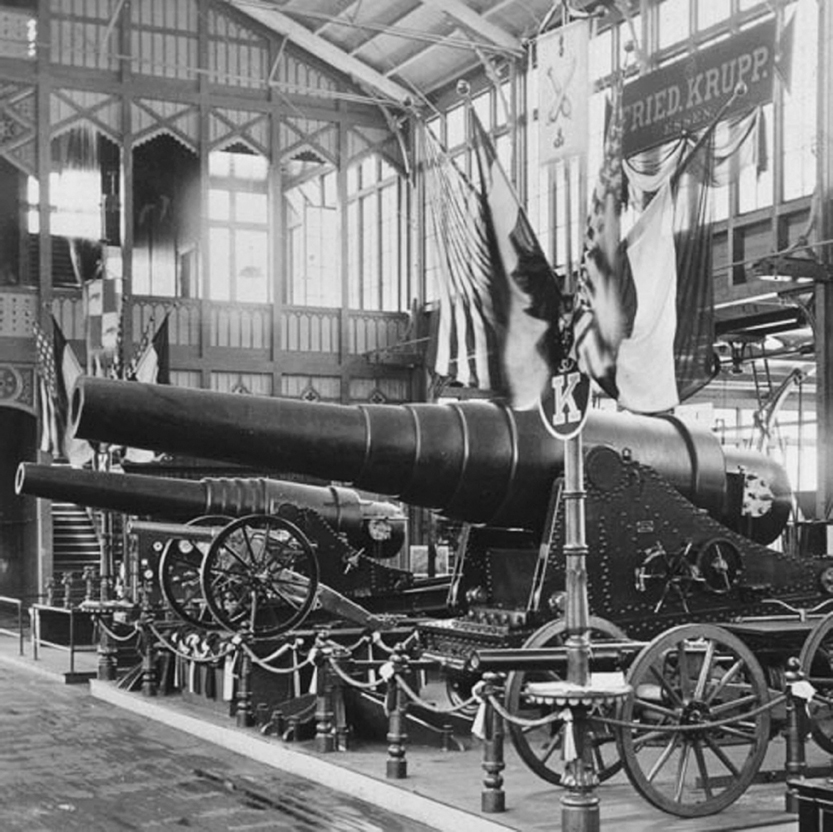

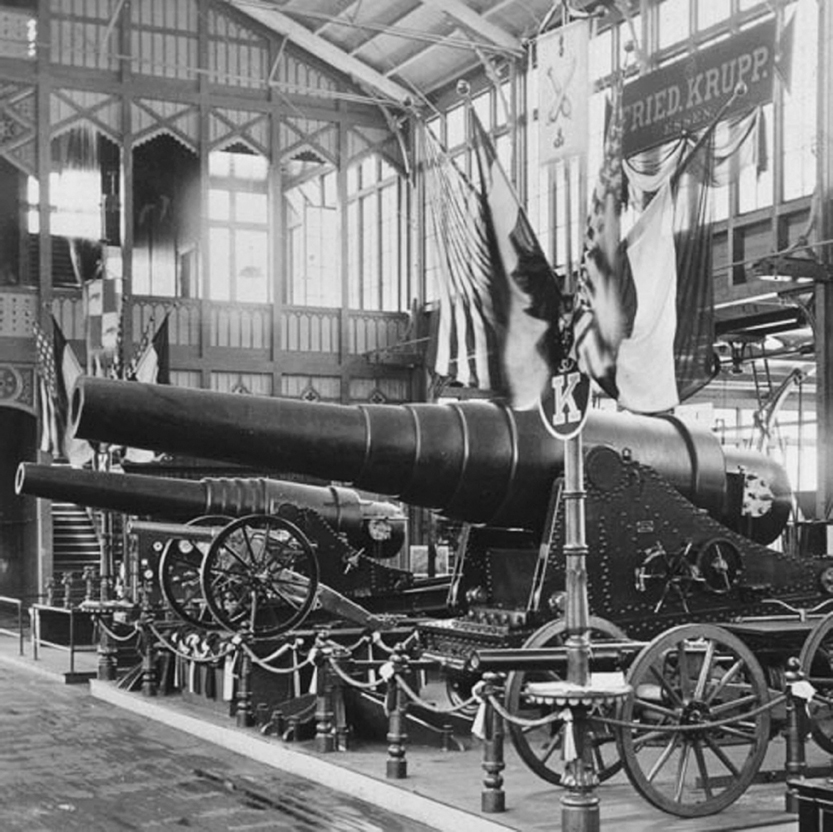

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 was the first Worlds Fair held in the United States. Philadelphia was the location, in celebration of a hundred years of American Independence. One of the most talked about and anticipated exhibits came from the Alfred Krupp armaments works in Essen, Germany. Not twenty yards from the main entrance of Machinery Hall stand two monsters, wrote the New York Times correspondent in the edition of 28 June 1876, speaking of two giant Krupp coastal defence guns. Krupp was being compared to Englands Sir Joseph Whitworth and William Armstrong and Americas Thomas Jackson Rodman as a builder of rifled ordnance which shall defy armour-plated leviathans and put the most powerful land batteries to confusion.

The Krupp guns were indeed monsters but in relation to similar heavy armament, they turned out to be not so extraordinary. The Krupp coastal defence gun was made of cast steel, with a 35.5cm diameter barrel, an 800cm long tube and a hydraulic recoil brake, the ensemble weighing 56kg. Tests showed it was able to penetrate the armour plating of British battleships from a distance of nearly a mile. It was larger than the Rodman but smaller than the Whitworth guns also on display in the hall. What made the Krupp guns extraordinary was the mystery surrounding them. They were described as monsters, to be used against Leviathans, but they also demonstrated the might of the new German empire and represented one element of the new military technology that would change the face of warfare in the next century.

A year later an obscure article appeared in the New York Times on 21 May 1877 comparing Krupps latest 80,000kg guncharacter, to the British models. The most interesting part of the article was the mention of a design by Herr Krupp of a 126-ton model with an 18-inch diameter bore, or approximately 45cm. Enemy naval vessels would certainly avoid going near a coastal battery equipped with a gun of this calibre, but a coastal defence gun was of no concern to fortress engineers in France and Belgium, because it could not be moved inland to fire on the forts. Unknown to the London Times and New York Times reporters who were writing about coastal guns at that time, Krupp would soon begin to develop large calibre siege guns that would result in the fielding of a massive 42cm gun.

Krupp guns on display at the Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, 1876. (LOC)

As late as 1890 the military engineers working on the new defences of eastern France and Belgium built their forts to resist a shell no larger than 21cm the largest known gun that could be transported by an army. Krupp might be developing very large coastal guns, but the Belgian forts at Lige and the French fortifications in Lorraine were 400km and 700km respectively from the closest German coastal battery and thus were not threatened at all by these monster artillery pieces. Not, that is, until they were designed to be disassembled and moved overland by train or mechanized tractor and set up to bombard the forts. They had no idea that Krupps designer, Professor Fritz Rausenberger, was working on a rail-transportable 42cm heavy mortar known as the Beta model. This would eventually lead to the development, in 1911, of a mobile, short-barrelled 42cm howitzer, the

Next page