Also by Ed and Libby Klekowski

Eyewitnesses to the Great War: American Writers, Reporters, Volunteers and Soldiers in France, 19141918 (McFarland, 2012)

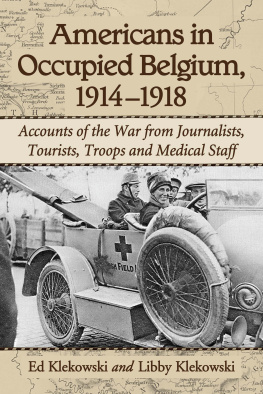

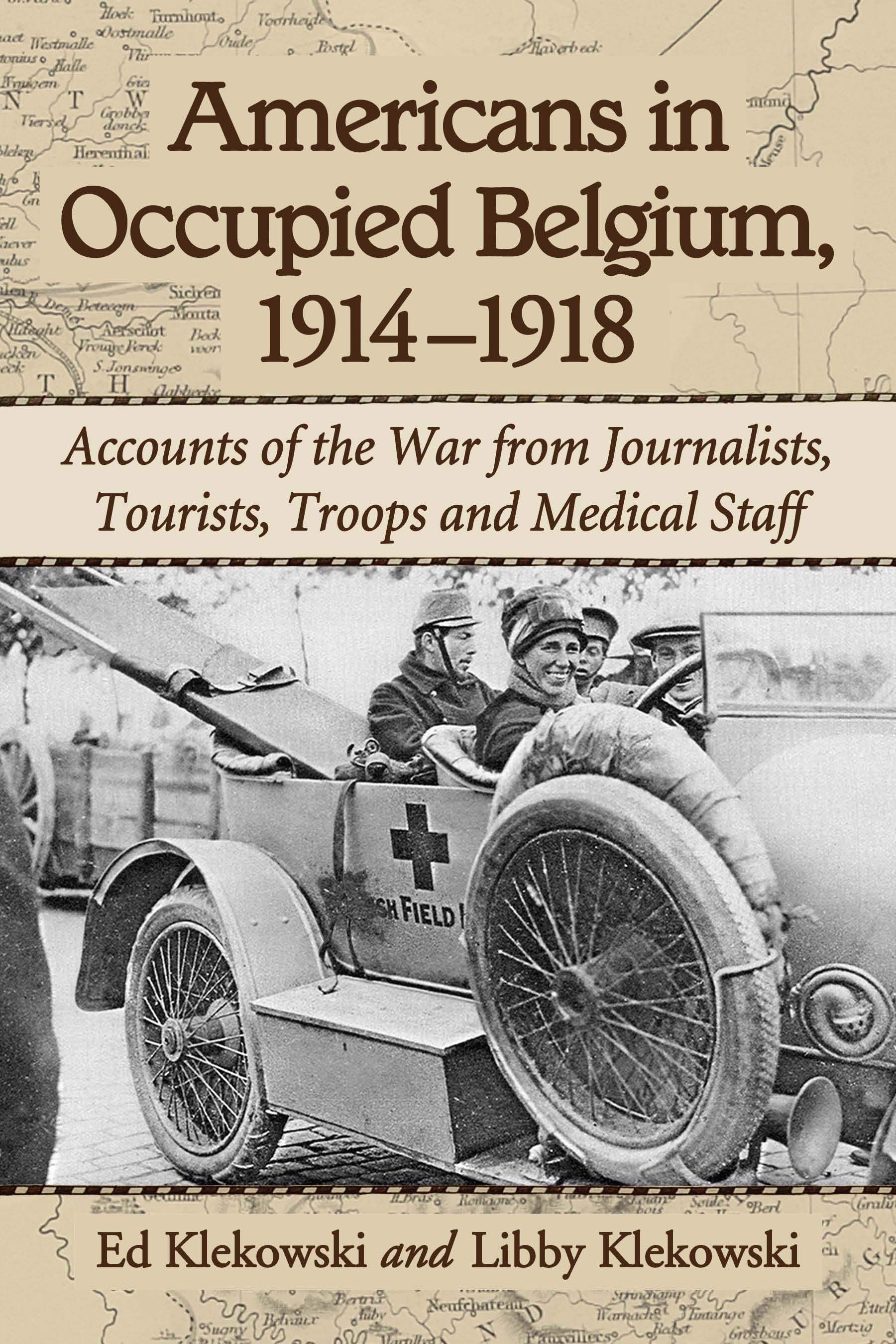

Americans in Occupied Belgium, 19141918

Accounts of the War from Journalists, Tourists, Troops and Medical Staff

Ed Klekowski and Libby Klekowski

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1487-8

2014 Ed Klekowski and Libby Klekowski. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

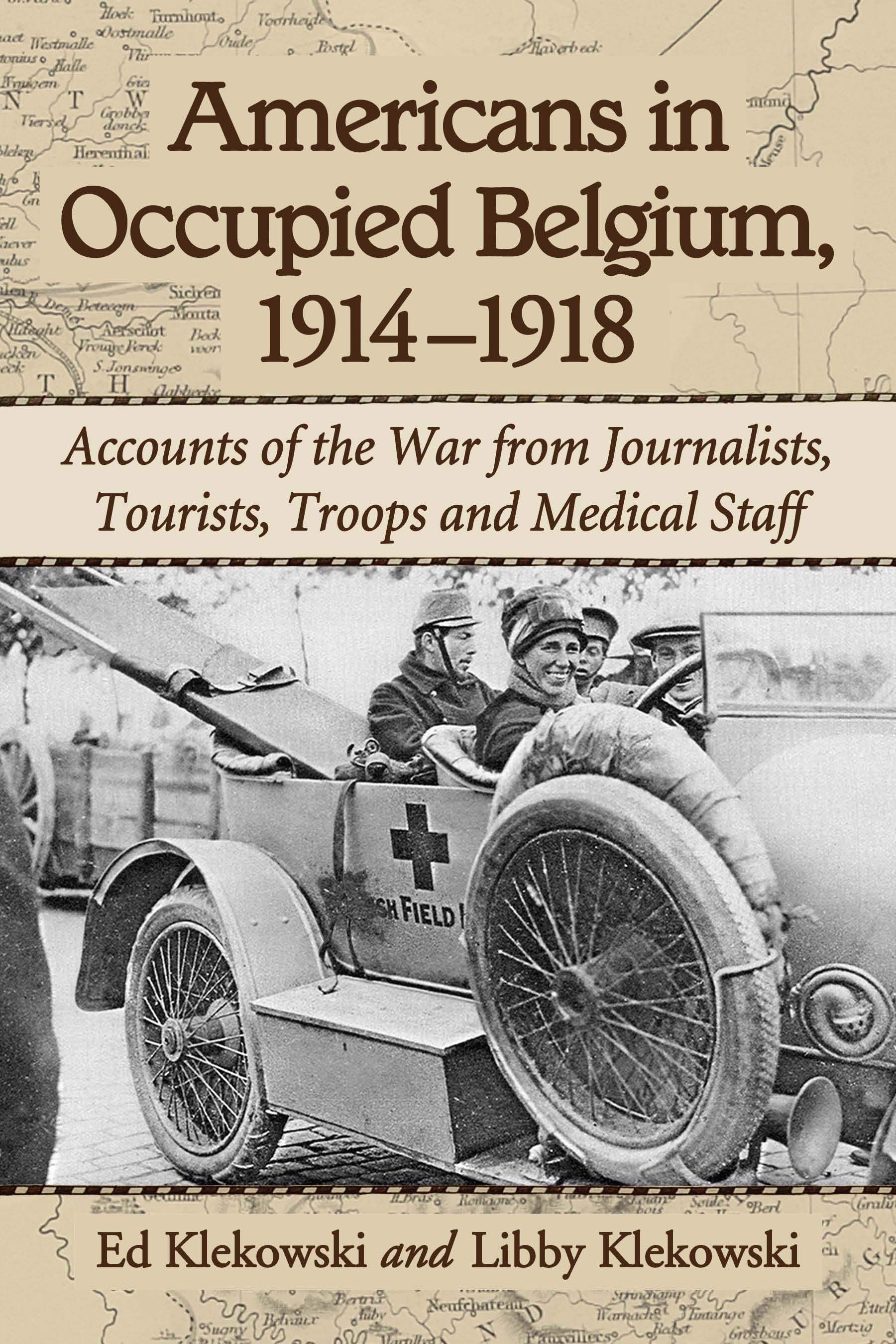

On the cover: Mrs. Winterbottom, ne Gladys H. Appleton, in her Minerva driving to one of the outer Antwerp forts to retrieve wounded (Le Miroir, 1914); background map of Belgium ( Hemera Technologies/Getty Images/Thinkstock)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Amanda, Ulrich, Philip and Alexandra,

our companions in exploring Belgium

Preface

Belgium in the First World Warthe first country invaded, the longest occupied, and when the war finally ended, the first forgotten. More than four years of carnage on the Western Front displaced from memory what happened behind the lines in Belgium. This is unfortunate because Belgium was, in many respects, a dress rehearsal for the civilian terrors of the Second World War. Nevertheless, for most Americans the history of Belgium during the Great War is only the history of the bloody battles around the Ypres Salient between the British and German armies. The authors were like most Americans regarding Belgium and the war, that is, until we got an opportunity to live there.

Our home for six months was the university town of Leuven (Louvain). Soon after arriving, as we explored our new home, we noted that most of the buildings in the town center had stone plaques affixed to their fronts with two dates inscribed: 1914 and a date in the early 1920s. We learned that the Imperial German Army had sacked the town in August 1914, and that the buildings with the dates were those destroyed during the sack and rebuilt in the 1920s. You could follow the extent of the destruction by following the plaques up and down the streets. Then there was our first visit to the university library. The building seemed old, but it was not. As we waited to enter, a university student asked us if we were Americans and if we knew the story of the library. We said yes to the first question and no to the second. She then gave us a brief guided tour. Covering the buildings faade were hundreds of stone memorial plaques with the names of American schools, colleges, associations, clubs, municipal departments, scientific and engineering societies. She explained these donors rebuilt the university library after the German Army burned the original library during the sack of 1914. One could say her tour was the inspiration that ultimately led to this book.

Before the war, Belgium had a large American colony, which included representatives of American companies, artists, writers and diplomats with the American Legation. When the war began, American journalists flocked to Belgium. There was more freedom of movement for the foreign press in Belgium than in either France or England. Perhaps the strangest American visitors in the early days of the war were war tourists, their passion being to witness battles and gorethey were, admittedly, a bit insane, but they left interesting memoirs. During the German occupation of Belgium, many Americans lived in Belgium and northern France supervising the activities of the Commission for the Relief of Belgium (C.R.B.). Other Americans volunteered as soldiers in the Canadian Army, became pilots in the Royal Flying Corps, or served as medical staff in the British Army; all saw action in the Ypres Salient battles. Remarkably, even after America entered the war on the side of the Allies and most of the non-military Americans left Belgium, a small group remained, tolerated by the German occupiers. Fortunately, many Americans left written accounts of what transpired in Belgium during the German invasion, occupation and final retreat. Their first-hand accounts are the basis of this book.

Since memoirs, magazine articles and newspaper reports from the war years were so important in understanding American experiences in Belgium, our first acknowledgment must be to the W.E.B. Du Bois Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. We especially thank Melinda McIntosh, reference librarian extraordinaire, for her enthusiasm and skills in researching our often obscure queries; Diane McKinney, interlibrary loan coordinator; Barbara Morgan, law reference librarian; Laura Quilter, copyright policy librarian; Robert Cox, head of special collections and archives; and the university librarians of the post-war years for assembling an incredible collection of First World War memoirs. Special thanks to the University of Massachusetts Biology Department for providing Ed a post-retirement office, his former department head James Walker for help with funding and Charlene Coleman for keeping track of the funds, and Thomas Carpenter for computer assistance.

We thank Nicole Milano of the Archives of the American Field Service, New York, for copies of letters by A. Piatt Andrew written during the Second Battle of Ypres, and Jean Paul De Vries and Brigitte De Vries of the Romagne 1418 Museum in Romagne, France, for making available to us all the war-time issues of Le Miroir. Rainer Hiltermann of Brussels deserves very special thanks for his tireless help. Rainer is the authority on all things pertaining to the German occupation of Belgium. He was generous with period pictures from his collection and gave us a bound set of Illustr 1914, a rare pictorial magazine published in occupied Brussels. We acknowledge the skill of Meg Clark, our graphic artist, who brought the photographs in Le Miroir and Illustr 1914 back to life. Maps are original and drawn using Inkscape software.

Of course, our special thanks to Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels and Ulrich von Koppenfels for their generous hospitality in Brussels and their suggestion we spend time in Leuven, and to Ulrich for reading the entire manuscript and for help in exploring Antwerp and Charleville (the latter always in the rain).

Regarding Belgian place names, memoirs and histories of the First World War use the French names for cities, towns and villages in Flanders. We have retained that convention but include the contemporary Flemish name in parentheses, e.g., Louvain (Leuven), Ypres (Ieper), Bruges (Brugge).

Introduction

If one examines the European War from the standpoint of pure reason, both its origin and development seem a chaos of improbabilities which could not have been foreseen by the most sagacious mind.Gustave Le Bon, war psychologist, 1916

The First World War caused the premature deaths of 9.5 million combatants and wounded 15 million. It was one of the deadliest wars in human history. So why was it fought? Moreover, why was Belgium so important?

The crisis began with the assassinations of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on June 28, 1914. Since the archduke was next in line to the Austro-Hungarian throne, his death had consequences; unfortunately, the consequences far exceeded his importance. In the United States, newspapers noted the royal murders but went on to more interesting news.

Next page