Praise for

THE HOTEL ON THE ROOF OF THE WORLD:

'One of the most strangely seductive places I've been to Thank you to Alec Le Sueur for bringing it to life'

Michael Palin

'A comparison with Fawlty Towers is inevitable, but this is funnier'

THE MAIL ON SUNDAY

'Le Sueur... provides us with the means of improving our knowledge of a far-away country about which we know little'

THE GUARDIAN

'Horribly funny and worthy of any hotel sitcom'

SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST

'Imagine moving Fawlty Towers from Torquay to Tibet... Le Sueur has distilled five years of real anecdotes into one hilarious volume'

FOCUS magazine

'This is a rip-roaring comedy of a book... Underlying the story is a heart-warming and sensitive understanding of the Tibetan people'

THE HIMALAYAN CLUB

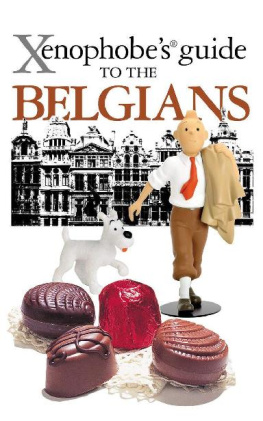

BOTTOMS UP IN BELGIUM

Copyright Alec Le Sueur, 2014

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

Alec Le Sueur has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-78372-048-4

p.200 beer description reproduced by kind permission of CAMRA.

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Nicky Douglas by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 756902, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: .

To Conny

8/7/19658/7/2011

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

W hen Julius Caesar passed through the low lands on his way to conquer Britain, he reported back to Rome that the tiresome Belgae were 'endlessly fighting amongst themselves and especially with the people from across the Rhine'. This tradition seems to have carried on for much of the next 2,000 years, and ownership of the land that we now call Belgium has been contested more times than practically any other piece of European soil. Whether by invasion, handed out as post-war spoils or wedding presents or through inheritance carve-ups, the 'under new management' sign has been hung up by the Vikings, Franks, the Holy Roman Emperor, the Burgundians, Hapsburgs, Spanish, Austrians, French and Dutch before the Belgians finally declared their independence in 1830. Even after independence, the Germans have had a go twice at running the country.

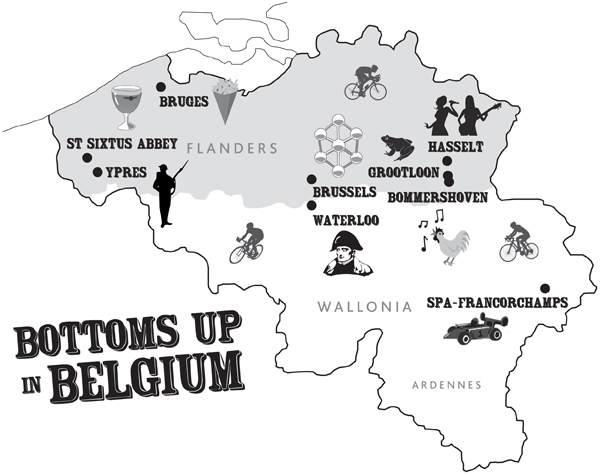

In between being wiped flat by invading armies, Belgium has been remarkably prosperous, with trade, textiles and the industrial revolution all bringing vast wealth to various parts of the country. This extraordinary history of continually shifting cultural, political, linguistic and economic power has led to Belgium's peculiar and complex make-up today. If you take a ruler to the map of Belgium and draw a horizontal line from left to right across the country, just beneath Brussels, this will give you the approximate language divide between north and south. Above the line is Flanders, inhabited by the Flemings whose language is Flemish. My wife Conny described the difference between Flemish and Dutch as that between English and American English, i.e. basically the same but with a different accent and some unique expressions. Below the line is Wallonia, inhabited by the Walloons, whose language is Belgian French, which again is really just French with a few twists, such as the simplification of the way the French say ninety-nine quatre-vingt-dix-neuf to the much easier, if childish sounding nonante-neuf.

But it's not that simple: above the line in the language divide is the Brussels region which stands out in a sea of Flemish speakers as an official bilingual island of French and Flemish. And then to the east of the country, if you take your ruler and draw a line vertically cutting off the small bulge in the middle-right of the map, is the home of Belgium's third official language the German speakers. Approximately 70,000 German-speaking Belgians live in nine municipalities along the BelgianGerman border with their own regional parliament and German language television, radio and newspaper. It's a 'little Germany' within the Walloon, French-speaking province of Lige, a glorious example of Belgian federalism; a state within a state within a state. To be more precise, it is two 'little Germanys': much like Sumatran orang-utans living in isolated pockets of rainforest separated by palm oil plantations, the two groups of German-speaking Belgians are separated from one another by a large swathe of French-speaking Lige, which cuts between the two cantons through the pine forests of the Ardennes to the east of Spa. The pockets of German-speaking Belgians have an official listing in UNCHR's World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples, the first step towards recognition as an endangered species.

French was once the language of the Belgian ruling class, with Flemish-speakers looked down upon as peasants, and the German-speakers dismissed out of hand as being German. Tensions, particularly between the FrancoFlemish language divide, still flare up every so often, usually around the boundaries of bilingual Brussels where heated debates over language rights periodically lead to constitutional crises and the toppling, or non-forming of governments. But do not worry; politics and language boundaries are not the subject matter of this book. I have included this explanatory note at the start merely to give readers who may otherwise not be aware a glimpse of the complexities and tensions that lie beneath the surface of this outwardly very ordinary-appearing country and to set the scene for references to Wallonia, Flanders and the Germans in the chapters ahead.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

U ntil 1993 I had never been to Belgium. I think I must have been through it at least once judging by the evidence of a Belgian tank driver's glove in our garden shed, but I had certainly never been to it. My father had picked up the glove from a Belgian roundabout on the way to our summer holiday in the Netherlands in 1969, collecting it as some kind of recompense for being stuck behind Belgian military manoeuvres for hours on end in a traffic jam that seemed to stretch the entire length of the Belgian coast. I was only six, so I don't remember much of the holiday apart from the sore point of missing one of civilisation's greatest historic moments. My older brother was very unfairly allowed to watch the first moon landing, live on a new colour TV set in the campsite games room, while I was sent to bed in the caravan in a serious strop, apparently being 'too young' to stay up. I also caught chicken pox that holiday, which I am sure was my brother's fault too, but I think that was in the Netherlands.