Introduction

The advance announcements for the auction had somehow escaped my attention. Traveling on a book tour, I had missed the news coverage and didnt even have time to order the sale catalog (as I sometimes do for research purposes in writing my books). Instead, two days before the auction, a small newspaper ad alerted me to the sale. The name of the auction was deceptively bland: Bonhams Fine Books and Manuscripts, to be held on Thursday, December 9, 2010.

The auction included several priceless artifacts: a copy of Dantes Divine Comedy from 1481, a second quarto edition of Shakespeares Julius Caesar from 1691, and a first edition of Ian Flemings James Bond thriller The Spy Who Loved Me . Certainly these were all choice items, and the bibliophile in me longed to possess these treasures, but they were not the items that caught my eye, that would put me on an early train leaving for New York City the next morning. Rather, it was a collection that Bonhams advertised unceremoniously as John F. Kennedy: The Photographic Archive of Cecil W. Stoughton.

I kneweven sight unseenthat this was no ordinary scrapbook collection of scratchy Polaroids and faded albums. No, this might be the treasure trove of one of Camelots court photographers, a man who had visually documented some of the most important events in the presidency of John F. Kennedy, including a secret party in New York City attended by the president and the most glamorous movie star of the time: Marilyn Monroe.

Captain Cecil Stoughton had a history of covering Kennedy events. He had started with JFKs inauguration on January 20, 1961, working for the US Army Public Information Office. Major General Chester Clifton, head of the office, had gotten Stoughton early access. Stoughtons photos of the inauguration impressed the president so greatly that he was brought on full-time as an in-house photographer, the first official White House photographer. There, Stoughton, a well-built man with thick dark hair, photographed John and Jacqueline Kennedy more frequently than any lensman alive.

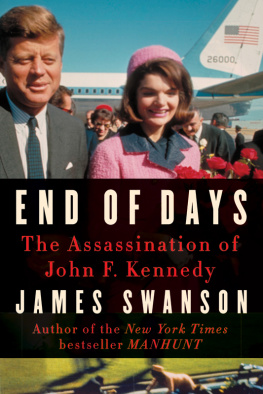

Stoughton had been present from the first to the last of the thousand daysJFKs unfinished presidency of two years, ten months, and two days. He was in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963, the final day, where he took one of the most memorable photographs of the twentieth century, a shocking image that symbolized the traumatic end of Camelot: the swearing in of the new president, Lyndon Johnson, at Love Field aboard Air Force One as a distraught and bloodstained Jacqueline Kennedy stood in shock beside him.

After his role in the Kennedy White House, Stoughton served as White House photographer for two years under LBJ and then became head stills photographer for the National Park Service, a position he held until his retirement in 1973. Later, people noted the chip on his shoulder. He complained often that he got no credit for his work. A Kennedy collector, who spoke to Stoughton often, said it was a recurring theme: He was resentful, bitter, and felt he had never gotten the recognition or reward that he deserved.

Stoughton had once shown off a handful of his treasures on an episode of PBSs Antiques Roadshow , and over the years he had even sold off a few choice pieces. But no one knew the full extent of his hoard. Stoughton died in 2008 at age eighty-eight, and two years later, his estate had consigned his archive to the auction block, just as relatives clear out a cluttered attic after a death.

For the next two days, I haunted Bonhamss Madison Avenue gallery. Stoughtons collection turned out to be enormousfar too many items to sell one at a time. The catalog had divided the collection into fifty lots, some containing a single piece, others up to a few thousand.

Strangely, few people attended the preview. For fifteen hours over two consecutive days, I had the collection almost to myself. I spotted the obvious treasures first: the iconic image of John Jr. and Caroline playing in the Oval Office, inscribed by JFK to Stoughton; a photo signed by Jackie and JFK; one of the presidents neckties; letters and notes from Jackie; and the holy grail of modern presidential photosLBJ taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One, inscribed by him to Stoughton.

The official photographer of the Kennedy White House, Cecil W. Stoughton, was responsible for one of the most memorable photographs of the twentieth centuryand countless others.

Only then did I see the rest: the thousands of photographs, some in binders, others in plastic bags, and some stacked in loose piles. For example, there were:

- 430 photos in lot 6200;

- 585 in lot 6218;

- 1,026 in lot 6219;

- 1,080 in lot 6220;

- 2,110 in lot 6222;

- 2,140 in lot 6223.

To view these photographs methodically, one by one, would have taken days. Instead, I grabbed them in bunches, flipping through them as fast as I could. It was a rapid-fire slideshow tour of Camelot that felt like an Andy Warhol art project. More than twelve thousand images of John and Jacqueline Kennedy burned into my memory cells. It was an almost hallucinogenic sance.

But the more I saw, the more disappointed I became. I had expected to find images of the Kennedys with warm, personalized inscriptions in gratitude to the man who had taken them. I wanted to construct how the myth of Camelot had been made, from the man who had been part of its visual making. I had hoped to see Camelot through another lensin this case, literally through a camera lens.

Many of the photos were small, measuring four-by-five inches instead of the usual eight-by-ten or eleven-by-fourteen. Many were group shots of events taken from a distance, and the human figures, even Jack and Jackie, were tiny without any revealing close-ups. To my disappointment, many of the color photos had faded, and most of them were later prints, not the vintage ones bearing the imprint of the White House photo lab, with an ink-stamped date (1961 to 1963) and code number on the reverse.

After two days, it was obvious: Cecil Stoughton was not a great photographer. His composition was awkward, unoriginal, and workmanlike. Stoughton did not possess the skills of Jacques Lowe or Mark Shaw, who also photographed the Kennedys. Stoughton had enjoyed privileged and practically unique access to historic moments, but, with a few exceptions, he had captured little of their human drama or significance. This wasnt artit was a kind of data entry. (In fact, Stoughtons fame isnt even based on any single image he took of JFK but rather of Lyndon Johnson.)