This story is true. All the characters are real and were alive during the great manhunt of April 1865. Their words are authentic. In fact, all text appearing within quotation marks comes from original sources: letters, manuscripts, trial transcripts, newspapers, government reports, pamphlets, books, and other documents. What happened in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1865, and in the swamps and rivers, forests and fields of Maryland and Virginia during the following twelve days, is far too incredible to have been made up.

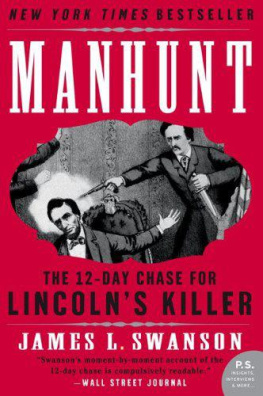

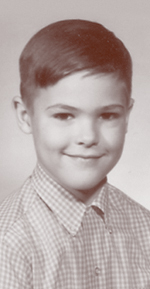

I was born on February 12, Abraham Lincolns birthday, and my fascination with our sixteenth president began when I was a young boy. On my tenth birthday, my grandmother gave me an unusual present: an engraving of the Deringer pistol John Wilkes Booth used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln, framed by a newspaper article (on page 17) published on the day after the assassination. The newspaper article described some aspects of the assassination, but was cut off before the end of the story. I knew I had to find the rest of the story. This book is my way of doing that.

The author as a boy

THE PRESIDENT AND HIS FAMILY

Abraham Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln

Thomas Tad Lincoln

GUESTS OF THE LINCOLNS AT FORDS THEATRE

Major Henry Rathbone

Clara Harris

PRINCIPAL CABINET MEMBERS

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

Secretary of State William H. Seward

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles

PRINCIPAL DOCTORS

Dr. Charles A. Leale

Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes

CONFEDERATE LEADERS

President Jefferson Davis

General Robert E. Lee

CONSPIRATORS

John Wilkes Booth

David Herold

Lewis Powell

George Atzerodt

Mary Surratt

John Harrison Surratt

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd

PRINCIPAL ACCOMPLICES

Thomas Jones

Captain Samuel Cox

PRINCIPAL MANHUNTERS

Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty

Luther Byron Baker

Colonel Lafayette Baker

Colonel Everton Conger

Lieutenant David Dana

Sergeant Boston Corbett

the United States endured a bloody civil war between Northern and Southern states. The conflict had begun long before over the right to own slaves and states right to secede, that is, to leave the Union if they disagreed with the government.

In the North, where the economy was based on factories and industry, most citizens considered slavery brutal, inhuman, and immoral. In the South, where the economy was dependent on slave labor, citizens believed they should have the right to own slaves. They also believed that if the national government disagreed with that right, Southern states had the right to secede.

Lincoln, elected president of the United States in 1860 just before the outbreak of the Civil War, held two strong beliefs: that slavery was morally wrong, and that the North and South must remain united as one country.

Southern soldiers, dressed in gray uniforms, were called rebels and Confederates. Northern soldiers, dressed in navy blue uniforms, were referred to as Union soldiers or Yankees.

The war lasted four years and resulted in more than 600,000 casualties, half of them lost to disease. After several bloody battles and costly, prolonged campaigns, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginiato Union General Ulysses S. Grant in the Virginia town of Appomattox Court House. But other rebel armies continued fighting in the field. Lees surrender did not mean the end of the war or of danger. Some Confederate sympathizers mourned the outcome of the war the lost cause would forever change the Southern way of life, including slavery. Many Southerners were unwilling to give up the lost cause, believing they could continue to fight and eventually win, or die trying. It was a dangerous place and time. With Lees surrender, soldiers shed their uniforms, turned in their weapons, and rode or walked home to resume their lives. Spies and Confederate sympathizers as well as soldiers filled the Union capital, Washington, D.C. People could not tell based on clothing, geography, or appearance which side of the conflict people supported.

It looked like a bad day for photographers. Terrible winds and thunderstorms had swept through Washington early that morning, dissolving the dirt streets into a sticky muck of soil and garbage. The ugly gray sky of the morning of March 4, 1865, threatened to spoil the great day. Photographer William M. Smith was to take a historic photograph of the presidential inauguration in front of the recently completed Capitol dome. Smith framed the view from the marble statue of George Washington on the lawn to the top of the dome, crowned by a statue of Freedom. Abraham Lincoln had ordered work on building the Capitol dome to continue during the war as a sign that the Union would go on.

Closer to the Capitol, Alexander Gardner set up his camera to photograph the inauguration. Gardner captured not only images of the president, vice president, chief justice, and other honored guests occupying the stands, but also the anonymous faces of hundreds of spectators who crowded the east front of the Capitol. In one photograph, on a balcony above the stands, a young man with a black mustache and wearing a top hat gazes down on the president. It is the famous actor John Wilkes Booth.

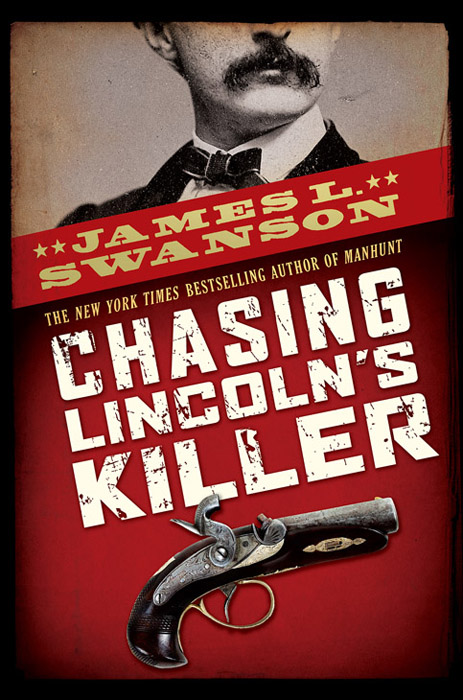

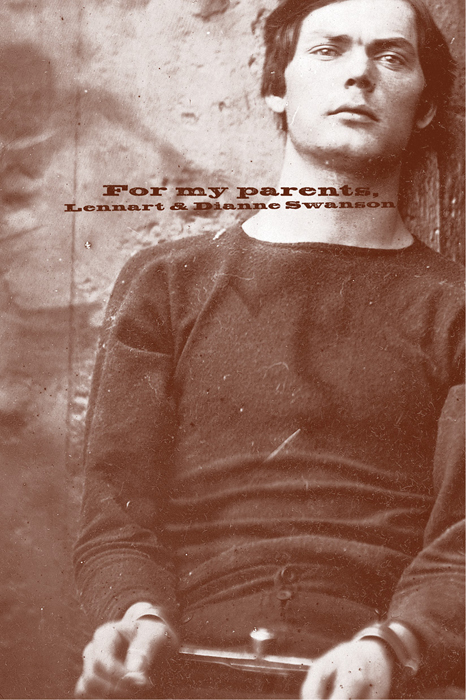

(Previous page) Perhaps the finest portrait of John Wilkes Booth ever made, this magnificent large-format photograph remains vivid evidence of Booths appeal.

Abraham Lincoln rose from his chair and walked toward the podium. He was now at the height of his power, with the Civil War nearly won. Clouds threatened another rainstorm. Then the strangest thing happened: The clouds parted and the sun burst out, flooding the spectacle. The presidents speech was brief just 701 words.

Next page