This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1954 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

INSIDE LINCOLNS CABINET

THE CIVIL WAR DIARIES OF Salmon P. Chase

EDITED BY

DAVID DONALD

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

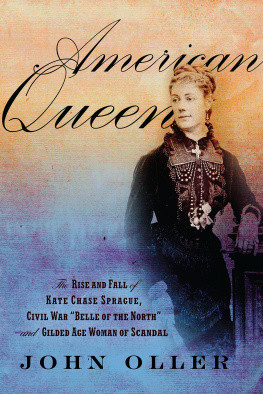

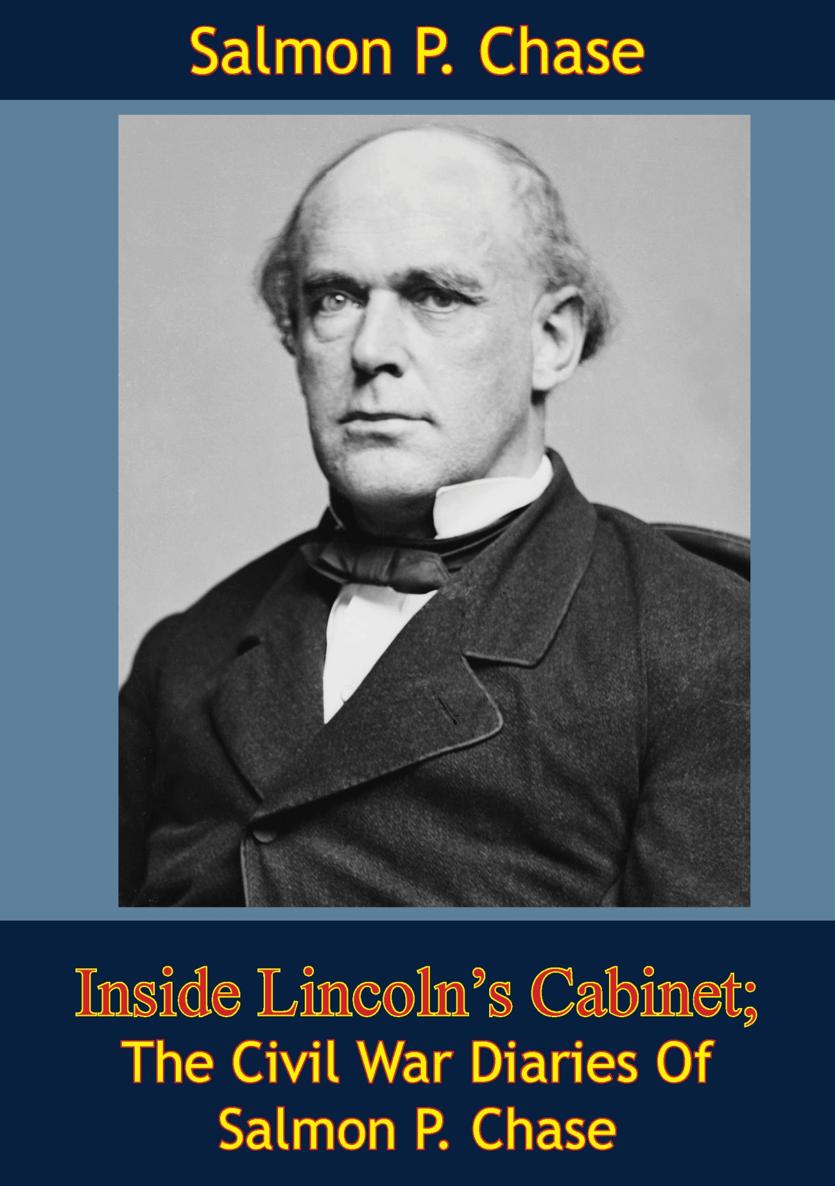

Brady Photographprints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

SALMON P. CHASE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

PREFACE

SOME of the best American diaries record the turbulent years of the Civil War. The voluminous journals of Gideon Welles, the terse records of Edward Bates, the witty jottings of John Hay, the dull entries of Orville Hickman Browning, the Pepysian diaries of George Templeton Strong, and the intemperate ravings of Adam Gurowski are all in print, and they provide eyewitness accounts of the Lincoln administration whose authenticity and importance are equalled by no other historical source.

Of the important Northern Civil War diaries, one has been unduly neglectedthe journals of Salmon Portland Chase, Lincolns Secretary of the Treasury. Because of a dispute between literary executors, the diaries became scattered shortly after Chases death. Some passages were published in the long, rambling Account of the Private Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase (1874), by Robert B. Warden, and others appeared in Jacob W. Schuckerss Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase (1874). Both books give skimpy, inaccurate, and unannotated entries wrenched from the journals. A portion of Chases diaries appeared, virtually without editorial comment, in the Annual Report of the American Historical Association for 1902 . It, like Warden and Schuckers, has long been out of print.

For a good many years I have hoped to edit Chases Civil War diaries, believing that the importance both of the man and of his position warranted publication, I have tried to present the diaries just as Chase wrote them. Beyond standardizing the dates which head each entry, I have not tampered with the text except, in the interest of clarity, by substituting the word and for the too-frequent ampersands. The diaries contain a number of errors, made either by Chase himself or by the copyist who transcribed the diaries presented in the first five chapters, but I have not thought it necessary to clutter the pages with sics . I have left names and places as Chase wrote them and have given the correct spellings in my notes. Annotating a diary in which so many characters appear, many in a quite fugitive fashion, has presented problems. In some cases I have not been able to trace down persons whom Chase mentions. Major characters have been discussed in the general introduction or in the opening paragraphs of each chapter, and most minor figures are identified in brief notes when first mentioned in the diaries. Rather than include an elaborate system of cross-reference notes, I have not annotated subsequent references to persons previously identified but have left that task for the index.

The Chase manuscripts are divided between the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Library of Congress, and without the assistance of those two great institutions the present volume could not have been undertaken. Except where otherwise indicated in the notes, Chapters I through VI are based on manuscripts in the Library of Congress, and Chapters VII and VIII on diaries in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

I am happy to say that Mr. Edwin Chase Hoyt has graciously given me permission to publish these records of his grandfather. The Columbia University Library and the New York Public Library have extended to me countless courtesies. To the officials of the Bowdoin College Library, I am deeply indebted for their generous hospitality to a summer visitor. And without the encouragement of Mr. John L. B. Williams, of Longmans, Green & Company, I should never have ventured to undertake this project.

The index for this book has been prepared by Mrs. Helen H. Metz, of Elmwood, Illinois, and I am deeply indebted to her for undertaking this tedious but important assignment.

D. D.

DEDICATION

For

My Mother and Father

INTRODUCTION

I

I HAD...the honour of shaking hands with old Abe, a visiting Englishman wrote from Washington in 1863. In appearance he is much better than I expected....He has [a] particularly pleasant smile, a very jolly laugh, and altogether looks like a benevolent and hearty old gentleman. Most other Federal officials made unfavorable impressions upon young Leslie Stephen, but among the mediocrities, one man stood out. The most remarkable of the other members of the Administration, Stephen judged, was Chase, a very fine, powerful-looking man. {1}

Salmon Portland Chase, Lincolns Secretary of the Treasury, looked as you would wish a statesman to look. {2} Wearing his blue broadcloth dress-coat with gilt buttons, a white waistcoat, and black trousers, {3} Chase was a figure to admire in any assembly. Tall, broad shouldered, and proudly erect, his features strong and regular and his forehead broad, high and clear, he was a picture of intelligence, strength, courage, and dignity. {4} The Secretarys reputation comported with his appearance. He had none of the talents of a great popular leader. His stately and occasionally pompous ways {5} permitted no familiarities from any man, for he had vowed early in his career never to seek popular acclaim by mingling with the populace, by base flattering of its passions, by drinking with it. {6} Nor was he an orator. When Rutherford B. Hayes first heard Chase speak, he reported the performance unimpassioned and spiritless. He appeared embarrassed and awkward, Hayes noted, lisped slightly. Not by any means so good a speaker as I expected to find him. {7}

Despite these handicaps, Chase became one of the major political figures of his age. Like so many other outstanding nineteenth-century AmericansClay, Webster, Calhoun, Douglas, Sumner, Blainehe failed to become President, but he achieved an unusual record of distinguished service in all three branches of the Federal government. During his six years in the Senate, to which he was elected as a Free Soil Democrat in 1849, Chase rapidly emerged as the ablest antislavery leader in Congress. While Seward maneuvered and Sumner orated, Chase organized the antislavery Congressmen and directed their course in the day-by-day debates. In 1854, outraged by Stephen A. Douglass Kansas-Nebraska Bill, which reopened the troubled issue of slavery in the Federal territories, Chase was principal author of the Appeal to the Independent Democrats, which blasted this gross violation of a sacred pledge...as part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region immigrants from the Old World and free laborers from our own States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inherited by masters and slaves. {8} When he entered the Senate, Chase had been invited to neither party caucus, for he was said to be outside of a healthy organization; when he left, he was a recognized founder and leader of the Republican party.