Contents

Guide

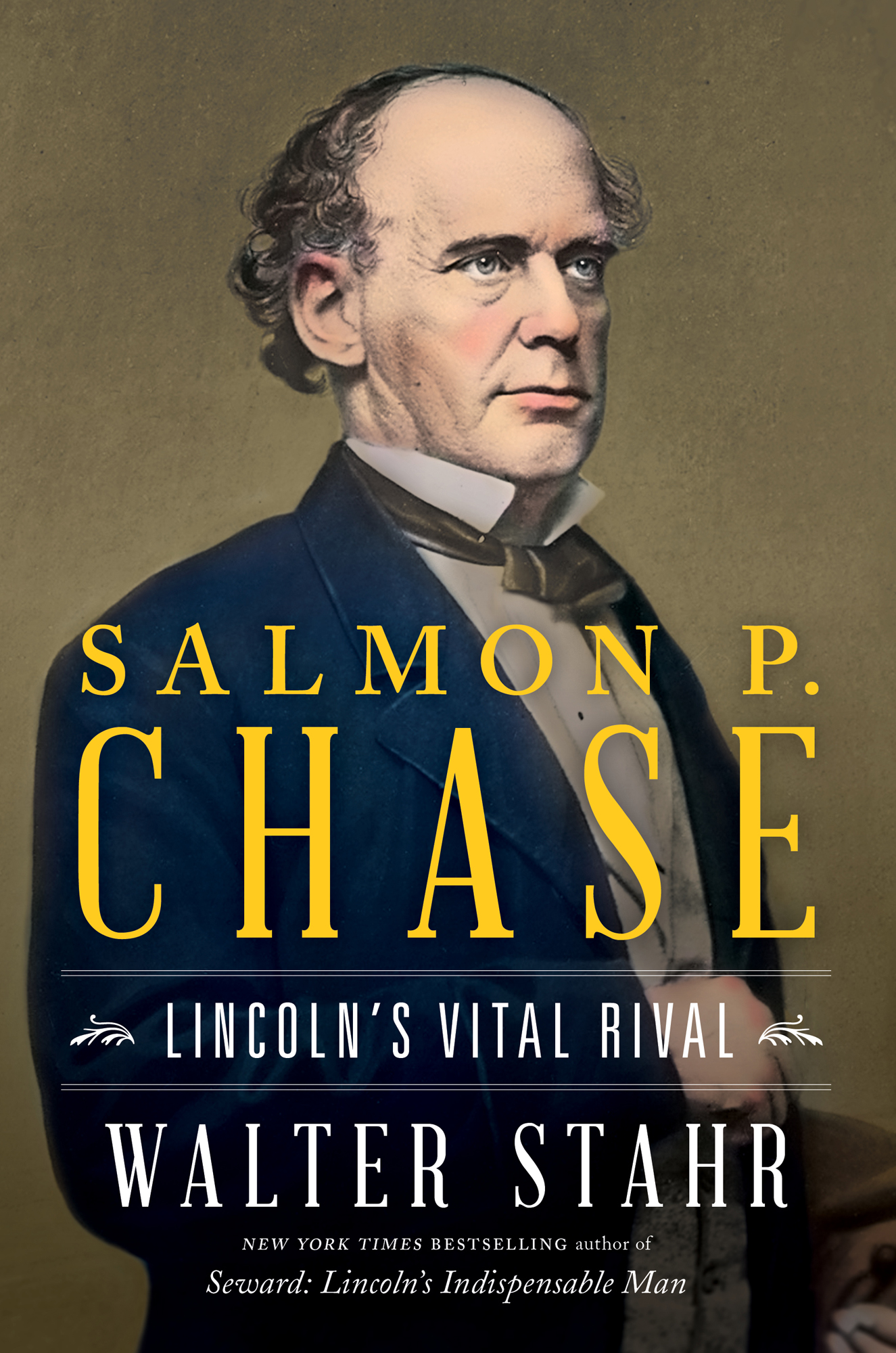

Salmon P. Chase

Lincolns Vital Rival

Walter Stahr

New York Times Bestselling author of Seward: Lincolns Indispensable Man

ALSO BY WALTER STAHR

Stanton: Lincolns War Secretary

Seward: Lincolns Indispensable Man

John Jay: Founding Father

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Walter Stahr

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition November 2021

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Kyle Kabel

Jacket design by Ryan Raphael

Jacket photograph by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-1-5011-9923-3

ISBN 978-1-5011-9925-7 (ebook)

In memory of John Roland Stahr

October 29, 1932, to October 14, 2020

Introduction

Z ion Church, the largest black church in Charleston, South Carolina, was packed for a political meeting on the afternoon of May 12, 1865. Most of the five thousand people present had started their lives enslaved and gained their freedom only a few weeks earlier, when the Union army finally arrived in town. The main topic for this meeting, as the last rebel die-hards fought the last battles of the Civil War, was reconstructionthe process of forming new state governments in the South, and whether blacks as well as whites would participate in this process. The afternoons first speaker, a white Union general, said that blacks had earned the right to vote through their service during the war. The remarks of the second speaker, a black army major, were interrupted by the arrival of the chief justice of the United States.

The black crowd stood and cheered, and the military band played Hail to the Chief, as Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase walked down the aisle and up to the platform. More than anyone else, he looked the great man, one of his friends recalled: six feet tall, solid, strong, clean shaven, nearing sixty. The crowd cheered Chase not because of his work on the Supreme Court (he had been chief justice only for a few months) or because of his work as Treasury secretary during the Civil War (although some called him Old Greenbacks for his role in creating the new green paper currency). No: the black Charleston crowd cheered because Chase was known as a lawyer who had defended fugitive slaves and a leader who, in his various government roles, had always argued against slavery and in favor of black rights.

Chase did not disappoint his audience. He said that their future was at last largely in their own hands. Let the soldier fight well, let the preacher preach well, let the carpenter shove his plane with all his might, and the planter put in and gather in as much corn or cotton as he can. Act thus, and I have no fears for your future. He told them that he had been speaking for black voting rights for twenty years, since a similar speech in Cincinnati, Ohio, but he cautioned that mere speeches did not have much effect, for in spite of his efforts, blacks still could not vote in Ohio. Chase had been pressing the new president, Andrew Johnson, to insist on black voting in the reconstruction process, and he believed that the president might well follow this course. If there was a delay, however, Chase advised the blacks of Charleston that they should go to work and show that the United States government was mistaken in making the delay. If you show that, the mistake will be corrected. When he finished, the crowd cheered Chase nine times.

Who was Chase, chief justice at this critical, fluid moment in American history? How did his views change from his youth, when he wrote that little cause exists for that sickly sympathy which many at the North feel or affect to feel with the fancied suffering of the slave, to his mature years, when he became a leading antislavery agitator? Why did the Republican Party, the party which Chase had done more than any other man to create, choose Abraham Lincoln rather than Chase as its presidential candidate in 1860? Why did Lincoln select his rival Chase for the vital task of managing the federal finances during the Civil War and then, near the end of the war, make him chief justice of the United States? And why was the chief justice touring the South in the last days of the Civil War and giving what many would view as a controversial, political speech?

Born in rural New Hampshire in 1808, Chase spent some of his youth in southern Ohio before returning east to attend Dartmouth College. After graduation, he lived four years in the nations capital, Washington, DC, teaching school and reading law. He moved to Cincinnati to start his legal career, where he married the first of three wives, all of whom died young. He was elected to the city council as a member of the Whig Party in 1840, but a year later, disgusted by the subservience of the two main political parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, to the slave states and the slave masters, Chase left the Whigs and joined the tiny Liberty Party.

Chases course, in the 1840s and early 1850s, was very different from that of Lincoln, another midwestern lawyer active in politics. While Chase was busy building and leading antislavery parties, Lincoln remained a loyal Whig, perhaps holding antislavery opinions but rarely expressing them in speeches. In the 1844 presidential election, Lincoln gave speeches for his Kentucky hero, the senator and slaveholder Henry Clay. Chase worked this year for the Liberty Party, publishing a Liberty Mans Creed, in which he declared that the party was simply carrying out the dreams of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, to end slavery through peaceful political processes.

A year later, Chase received a silver pitcher from the free blacks of Cincinnati to thank him for his legal work representing those accused of being fugitive slaves. In a speech that would often be quoted against him, Chase urged the state to amend its constitution so that blacks would have the right to vote. True democracy makes no enquiry about the color of the skin, or the place of nativity, or any other similar circumstance, he said. Lincoln, in the course of his long legal career, never represented a fugitive slave; he once served as lawyer for a master in an attempt to keep a black woman and her children in slavery in the free state of Illinois. Chase represented alleged fugitives so often that he was known as the attorney general for runaway negroes.

In 1848, near the end of his single term in Congress, Lincoln campaigned for the Whig presidential candidate, Zachary Taylor, another southern slaveowner. Chase was the key leader that year in forming the Free Soil Party, a combination of the Liberty Party with antislavery elements of the Whig and Democratic Parties. After the Free Soil national convention, of which he was the presiding officer, Chase campaigned relentlessly for the Free Soil Party, helping it secure almost 15 percent of the votes in the northern states. Early in the next year, an even split between the two major parties in the Ohio legislature allowed the Free Soil Party, through a coalition with the Democrats, to send Chase to Washington as one of the states two federal senators.