2010 by David Hirsch and Dan Van Haften

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-932714-89-0

Digital Edition ISBN 978-1-61121-058-3

05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1

First edition, first printing

Published by

Savas Beatie LLC

521 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1700

New York, NY 10175

Editorial Offices:

Savas Beatie LLC

P.O. Box 4527

El Dorado Hills, CA 95762

Phone: 916-941-6896

(E-mail) editorial@savasbeatie.com

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, please contact Special Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, or you may e-mail us at sales@savasbeatie.com, or visit our website at www.savasbeatie.com for additional information.

Dedicated to our parents

Robert Hirsch

Florence Hirsch

James Van Haften

Esther Van Haften

I know of nothing so pleasant to the mind, as the discovery of anything which is at once new and valuable nothing which so lightens and sweetens toil, as the hopeful pursuit of such discovery. A capacity, and taste, for reading, gives access to whatever has already been discovered by others. It is the key, or one of the keys, to the already solved problems.

Abraham Lincoln, Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society (September 30, 1859)

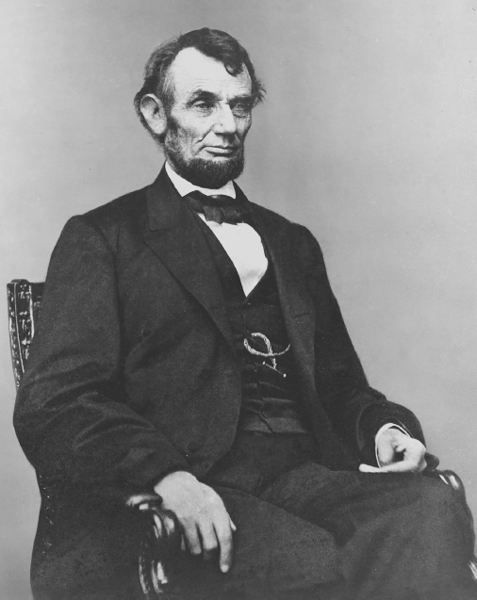

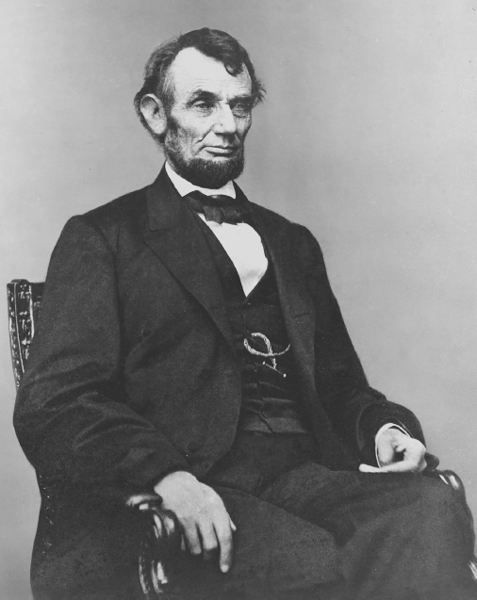

Abraham Lincoln

National Archives

Tables and Figures

Preface

The process of two people writing a book like this could be the subject of another book. There are so many variables regarding collaborating, sharing information, sharing writing tasks, joint editing and more. With one author in Des Moines and the other in suburban Chicago, face-to-face collaboration was possible only occasionally. It helped that the authors initially met decades ago, in the first grade.

When the authors began the three-year endeavor that produced this book, neither considered himself a Lincoln scholar. That was both an advantage and a disadvantage. The advantage was that the authors had few pre-conceived notions, and of necessity were willing to go wherever the evidence led.

David Hirsch had believed for many years that there was a connection between mathematics and speech. But prior to our Euclid discoveries, the draft of our book contained a mere sentence to the effect that English and mathematics are the two most important areas to study for someone planning a career in American law. However, early on in the project, Dan said the first thing he wanted to read was the complete Lincoln-Douglas debates, and the next thing after that was the Cooper Union speech. David thought that was an unusual place to start, but figured if that was what Dan wanted to do, then fine. Dan did a seven-page summary of key statements from the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

David became excited over a paragraph that mentioned Euclid. David asked Dan to find out everything he could about Lincoln studying Euclid. As with so much of Lincolns early years and law practice years, there were references in numerous places to Lincolns Euclid studybut none of them said much, and all of them said essentially the same thing: Lincoln studied the first six books of Euclid. He learned Euclid to find out what it meant to demonstrate.

So when Dan came back essentially empty-handed in his search for what Lincoln had learned from Euclid, David suggested: Do what Lincoln did. Go read Euclids first six books. Find out what Lincoln learned. Discover what demonstrate means.

Dan therefore studied Euclid, and Proclus commentaries on Euclid. He then felt he knew what Lincoln had learned. Davids response was, Good. Now find the best example of Lincoln using Euclid, preferably from his legal work, but if not there, then from his speeches. Almost none of Lincolns jury arguments and appellate oral arguments were preserved. After lengthy study, Dan came back: Ive got it: the Cooper Union speech. That was our primary starting point; this book is the end product.

In a contemporary context, this is the book Lincoln might have written about the vocation that was his passion. In that sense, weHirsch and Van Haftenare merely the books editors. The book largely relies on Lincolns words, as they are preserved, as well as the words of those who personally knew him. This book is also the result of the labor of all who came before us, who contributed to the preservation of the Lincoln legacy, from William Herndon to Harold Holzer, Frank Williams, John Stauffer, and countless others. The authors feel lucky and privileged to have put this book together.

Acknowledgments

Abraham Lincoln is addictive. If such an addiction is going to be indulged to the extent of writing a bookparticularly a book like thisit is rewarding to do so with a co-author one has known since the first grade. This book would not exist if not for the collaboration of one with the other. Neither would this book be what it is without generous support from others, too many to list, and likely too many to remember. The people and institutions mentioned below greatly enhanced the book. The responsibility for any errors in the book belongs solely to the authors.

Lee and Betty Moorehead organized annual three-day Lincoln seminars in Springfield for many years. Dan attended three of these seminars, where he learned about Lincoln scholarship and the Lincoln Legal Papers. Thanks to Betty for providing access to Lees collection of Lincoln books.

The American Bar Association provided a forum in the ABA Journal for David to co-author the technology column for more than a decade. Particular thanks to Steve Keeva, Davids first editor at the ABA Journal , who taught David to appreciate the value of an editor, and Reg Davis, Davids last editor at the Journal , who facilitated the February 2007 column on Lincoln that led directly to this book.

John R. Austin, Director of the David C. Shapiro Memorial Law Library, and Frank Lima, plus the staff of both the law library and Founders Memorial Library at Northern Illinois University, provided consistent support and assistance. These were the most heavily used libraries for this project.

The patient staff of the Drake University Opperman Law Library extended many courtesies, including research assistance, never fining David for an overdue book, and renewing his checked-out books without question. The Cowles Library at Drake University is appreciated for its shelves of Jefferson books we pored over the weekend we made the Jefferson discovery (that resulted in Chapter Thirteen): the excitement there was finding nothing, despite rows of books discussing Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration. The staffs of the University of Chicago DAngelo Law Library, DePaul University Rinn Law Library, University of Iowa College of Law law library, and the University of North Carolina Kathrine R. Everett Law Library were generous with their assistance.