1. Los Especiales Algeciras

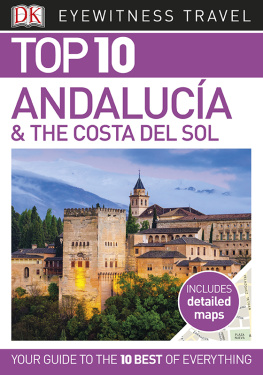

A brilliant November morning with a sky of diamond blue above the bay and the red flowers of a long summer still glowing darkly on the Rock. The intense blackness of the lampless night had rolled away to reveal, incandescent on the northern horizon, the country we had come to seek. It crouched before us in a great ring of lion-coloured mountains, raw, sleeping and savage. There were the scarred and crumpled valleys, the sharp peaks wreathed in their dusty fires, and below them the white towns piled high on their little hills and the empty roads running crimson along the faces of the cliffs. Already, across the water, one heard, or fancied one heard, the sobbing of asses, the cries and salty voices cutting through the thin gold air. And from a steep hillside rose a column of smoke, cool as marble, pungent as pine, which hung like a signal over the landscape, obscure, imperative and motionless.

So we left Gibraltar to its trim English streets, to its Genoese money-changers, Maltese tobacconists, Hindu silk-merchants and crook-boned Cockney soldiers, and we went down to the quay and gathered our bags and boarded the ferry for Spain.

The ferry flew the Spanish flag, had paddle-wheels, and was old, black-funnelled and squat as a duck. It was the type one might have seen, a hundred years ago, running missionaries up the Congo, loaded with whips and bibles. But today, being Saturday, it was packed to the rails with smugglers. As we moved across the oil-blue waters, innocent in the naked sun, they disposed their Gibraltar loot about them. Strapped to their limbs, under their clothes, went cigarettes, soap, sweets, tinned milk, coffee, corned beef and jars of jam. Then the port of Algeciras drew near, and fishermen cried to us from their boats, and we bounced off a yacht, bumped heavily against the quay, and tied up in a tangle, and landed.

The acid-yellow stones, the quay littered with straw and palms, the green-cloaked policemen carrying pistols, the lax and amiable formalities of passports and customs; then we stood free at last upon the ground, surrounded by Spain and the smell of fish-boxes. I turned then and spoke, after many years, my first words of Spanish, to a porter, and we understood each other. We bargained, our baggage was loaded on to a hand-cart, and we entered the town.

And here was the scene so long remembered: the bright faades still crumbling in the sun; the beggars crowding the quaysides, picking up heads of fish; the vivid shapely girls with hair shining like pitch; the tiny, delicate-stepping donkeys; and the barefoot children scrambling around our legs. Here were the black signs charcoaled starkly on the walls: Pension La Africana; Vinos y Comestibles, Espaa Libre, Amor! Amor! Here were the bars and the talking men, the smell of sweet coac and old dry sherries. A clear cold air, churches and oranges, and a lean-faced generation moving against white walls in sharp silhouettes of scarlet and black. It did not take more than five minutes to wipe out fifteen years and to return me whole to this thorn-cruel, threadbare world, sombre with dead and dying Christs, brassy with glittering Virgins.

We took a room in a hotel which stood close to the harbours edge, high above the masts of the fishing boats. It was called The Queen of the Sea, and its walls were faced with the wave-blue tiles of Seville. Its dining-room was a patio of pillars standing under a green-glass roof, and its green furniture was hand-painted with roses, hunting dogs and bulls. The proprietor was a swarthy Moor, morose, fat-necked, with a Farouk-like paunch. He spent his days chewing cold fat pork and playing glum games with the cash register. Ramn, the manager, who was quiet and courtly, had a long dark face of extreme nobility and torment. The rest of the staff included six chambermaids, four waiters, three kitchen-maids, two washer women, a clerk, a cook, a pageboy, a night-watchman and a turnkey. Yet this hotel was one of the cheapest in the town.

We soon settled in and the place served us well. It was an active, busy inn. The rooms were full of coughs, groans, cries and laughter; the stairways full of the songs of chambermaids, and the beds full of fleas the progenitors of long exhausted dreams. But the food was plentiful. Our first meal, served at half-past two that afternoon, offered us olives, sardines, shellfish, prawns, a large dish of rice served with meat and saffron, flan and fruit, and a bottle of wine fetched in for a shilling.

After such a meal, drenched in the green, brutish, stimulating oils of the hills, there was nothing one could do. So we climbed to our room overlooking the bay and lay in a lethargy till five oclock while the girls in the sewing-room above sat singing the languorous songs of their villages.

At five oclock there was a new awakening. The caf tables on the pavement below began to fill up with the customers of the evening. Waiters ran to and fro with prawns and manzanilla. Minstrels struck up on guitars and mandolines. There also arrived an army of touts and merchantsshoeblacks, newsboys, lottery-ticket sellers, gypsies with charms, boys with combs and postcards, women with baskets of cakes and sweets. Among the throbbing chords of the musicians arose their high-pitched cries: Ay, came membrillo !, Ay, dulces buenas!, Limpia! Lhnpia!; Africa de hoy! It was time to be up and about.

So I went forth into the town and tried to reacquaint myself with the pattern of it. But of course it was not the same at all. My memory, over the years, had torn the old town down, rebuilt it, laid out the streets in quite different order and obliterated some of their most dominating landmarks. In that time I also had been torn down, rebuilt and had many landmarks obliterated. The town, after all, remained the truth, and I the shifting fable.

I struck up through the narrow streets that I could not remember and that remembered me not. Yet here were the same square, gold-roofed houses with their grilled mysterious windows, the same delicate clusters of ironwork clamped to the warm white walls, the same bougainvilia and morning glory stretching forth their membranes of blue and purple over all. There was the same harsh singing in the patios, the same snap of wit in the air, the same smells of oil, of wine and charcoal, of raw fish and the raw sea.

Those years ago I had walked in from Cdiz, with my violin on my back, and lodged at the old inn of San Antonio where I used to pay threepence a night to lie on a sack of straw in the courtyard. I went now and found the place. Mules and tasselled harness and blue-painted wagons still crowded the courtyard. Carters and their families crouched on the cobbles cooking up soup on little braziers. Wine-skins hung from the walls, and the corners groped with echoes. But the old proprietor was dead, and the hunchback porter was dead, and Maria the maid had flown with a Moor, and nobody would believe, looking at my English tweeds, that I had ever been there at all.