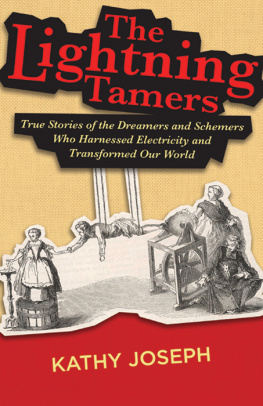

Copyright 2022 Kathy Joseph

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed Attention: Permissions Coordinator, at the address below.

http://www.smartsciencepress.com

ISBN: 979-8-9859813-0-8 (paperback)

ISBN: 979-8-9859813-1-5 (ebook)

ISBN: 979-8-9859813-2-2 (hardcover)

Ordering Information:

Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, and others. For details, visit http://www.kathylovesphysics.com.

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the archivists. Thank you for finding, preserving, and scanning, not just old scientific papers but also old newspapers, magazines, letters, and even diaries. This book would be nothing without you.

T he spark for this book was lit around eight years ago when I was at a dinner party and told a story of how I asked my students where electricity comes from and one of my students confidentially told me, The wall. This response, while technically correct, wasnt exactly what I was hoping for. A woman at the table chuckled and then admitted that she, too, would have responded with, The wall. She added that even if shed thought of generators or different kinds of power stations, it wouldnt have mattered, because she felt that she understood none of it. Although she used electricity every day and was completely dependent upon it, it was an utter black box. After I gave her an impromptu physics lesson, she seemed excited to understand the world a little better. This made me realize that there was a desire for people to understand where electricity comes from, and this is ultimately what inspired the audacious thought of someday writing a book on the subject.

At around the same time, I showed my students a clip from a Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) documentary called Einsteins Big Idea. The video showed an actor portraying a young Michael Faraday and his dramatic rise from binding books to being an assistant to Englands most famous chemist and to eventually discovering the electric motor. After watching the same clip, year after year, for five classes in a row, I became fascinated with the history of science. It started to hit me that discoveries didnt come from thin air but were developed by real people with real stories and real trials and tribulations.

As Marie Curie once elegantly wrote, The life of a great scientist in their laboratory is not, as many may think, a peaceful idyll. More often it is a bitter battle with things, with ones surroundings, and above all with oneself. A great discovery does not leap completely achieved from the brain of the scientist, as Minerva sprang from the head of Jupiter. Inspired by that video, I thought it would be interesting to write a book that explained how electricity was discovered by telling the stories of the personal history of the men and women who discovered it. Something that described not only how electricity works but how we got electricity to work. However, it was only several years after I had this idea when I had the time to try my hand at this project.

While researching the history of electricity, I made three important realizations. The first discovery I had was that Faraday wasnt the only one who had an interesting life story. Every scientist I encountered had a fascinating life with twists and turns and amusing anecdotes. Despite our image of a scientist being only a certain type, I found a wide range of personalities: some were quiet and studious, while others were flamboyant, artistic, cruel, romantic, or even totally insane!

The second surprising realization I made from my investigations is that no discovery, no matter how much it changed our understanding or our daily lives, was dramatically different from what was known before. For example, a shoemaker and retired soldier named William Sturgeon discovered the electromagnet in 1824 when he put current in a wire wrapped around an iron bar and found that it acted like a strong bar magnet. However, Sturgeon only did that because he was copying a French scientist named Andr-Marie Ampre who had discovered that wires could work like weak magnets if they were wrapped in a spiral around a glass bar.

Similarly, Ampre only conducted that experiment because a Danish scientist and philosopher named Hans Christian Oersted discovered that current in a wire would move a magnet, which made Ampre believe that he could make magnets out of electricity. Of course, Oersted was only able to conduct his experiment because Volta invented the battery first. Following the pattern, Volta only invented the battery because he was in a philosophical debate about the nature of electrical fire with a doctor named Galvani who discovered that two different metals would make a dead frog jump, and on and on. Every idea, every invention, is linked in a human chain of discovery. Nothing is completely new.

The third surprising realization I made as I read about these discoveries was that the words of the original scientists led me to have a deeper understanding of the science itself. I feel honored to have met all the great scientists and inventors in this book and am grateful to have learned more about the science of electricity from them.

My hope is that you, irrespective of your scientific background, learn something new from the amazing, delightful, and at times, infuriating people who are profiled in this book.

[Do not] despise the small beginningsthey precede of necessity all great things. Vesicles make clouds; they are trifles light as air, but then they make drops, and drops make showers, rain makes torrents and rivers, and these can alter the face of a country.

Michael Faraday (1858)

T here used to be an odd commercial on late-night television for the amazing static duster. What made it so amazing, and why I was a little obsessed with it, was how, after you removed a plastic sleeve, dust would fly toward the duster. The people in the commercial would gasp with amazement as dirt, stray paper, feathers, and even parts of their hair would zoom toward the duster like magic (although I still dont know why you want your duster to attract the hair on your own head).

Of course, the people who sold these devices were aware that this was static electricity in action, which is why they named it the amazing static duster. What they might not have known was that the first glimpses of modern electricity started with the study of this same strange, amazing power. It was this seemingly inconsequential study that was to form the foundation of our electric universe.

Ready to learn about folks rubbing objects and then staring intently at floating feathers and pieces of fluff? Lets go!

I would like to start with an Elizabethan doctor named William Gilbert (15441603), who is often referred to as the Father of Electricity. Gilbert was the first person whom we know of who scientifically studied electricity, and his studies made him famous. In the painting below, you can see him demonstrating static cling to Queen Elizabeth. But what, you might ask, inspired a medical doctor like Gilbert to study static cling, and why would that interest the queen of England?

Next page