PUBLISHED TITLES IN THE GREAT DISCOVERIES SERIES

Sherwin B. Nuland

The Doctors Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever,

and the Strange Story of Ignc Semmelweis

Michio Kaku

Einsteins Cosmos: How Albert Einsteins Vision Transformed

Our Understanding of Space and Time

Barbara Goldsmith

Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie

Rebecca Goldstein

Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gdel

Madison Smartt Bell

Lavoisier in Year One: The Birth of a New Science

in an Age of Revolution

George Johnson

Miss Leavitts Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman

Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe

David Leavitt

The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing

and the Invention of the Computer

William T. Vollmann

Uncentering the Earth: Copernicus

and The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

David Quammen

The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution

Richard Reeves

A Force of Nature: The Frontier Genius of Ernest Rutherford

Michael Lemonick

The Georgian Star: How William and Caroline Herschel

Revolutionized Our Understanding of the Cosmos

Dan Hofstadter

The Earth Moves: Galileo and the Roman Inquisition

ALSO BY LAWRENCE M. KRAUSS

Hiding in the Mirror

Atom

Quintessence

Beyond Star Trek

The Physics of Star Trek

Fear of Physics

The Fifth Essence

LAWRENCE M. KRAUSS

Quantum

Man

Richard Feynmans Life in Science

with corrections by Cormac McCarthy

ATLAS & CO.

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN , 19181988

Contents

Introduction

I find physics is a wonderful subject. We know so very much and then subsume it into so very few equations that we can say we know very little.

R ICHARD F EYNMAN , 1947

I t is often hard to disentangle reality from imagination when it comes to childhood memories, but I have a distinct recollection of the first time I thought that being a physicist might actually be exciting. As a child I had been fascinated with science, but the science I had studied was always removed from me by at least a half century, and thus it hovered very close to history. The fact that not all of natures mysteries had been solved was not yet firmly planted in my mind.

The epiphany occurred while I was attending a high school summer program on science. I dont know if I appeared bored or not, but my teacher, following our regularly scheduled lesson, gave me a book titled The Character of Physical Law by Richard Feynman and told me to read the chapter on the distinction between past and future. It was my first contact with the notion of entropy and disorder, and like many people before me, including the great physicists Ludwig Boltzmann and Paul Ehrenfest, who killed themselves after devoting much of their careers to developing this subject, it left me befuddled and frustrated. How the world changes as one goes from considering simple problems involving two objects, like the earth and the moon, to a system involving many particles, like the gas molecules in the room in which I am typing this, is both subtle and profoundno doubt too subtle and profound for me to appreciate at the time.

But then, the next day, my teacher asked me if I had ever heard of antimatter, and he proceeded to tell me that this same guy Feynman had recently won the Nobel Prize because he explained how an antiparticle could be thought of as a particle going backward in time. Now that really fascinated me, although I didnt understand any of the details (and in retrospect I realize my teacher didnt either). But the notion that these kinds of discoveries were happening during my lifetime inspired me to think that there was a lot left to explore. (Actually while my conclusion was true, the information that led to it wasnt. Feynman had published his Nobel Prizewinning work on quantum electrodynamics almost a decade before I was born, and the ancillary idea that antiparticles could be thought of as particles going backward in time wasnt even his. Alas, by the time ideas filter down to high school teachers and texts, the physics is usually twenty-five to thirty years old, and sometimes not quite right.)

As I went on to study physics, Feynman became for me, as he did for an entire generation, a hero and a legend. I bought his Feynman Lectures on Physics when I entered college, as did most other aspiring young physicists, even though I never actually took a course in which these books were used. But also like most of my peers, I continued to turn to them long after I had moved on from the so-called introductory course in physics on which his books were based. It was while reading these books that I discovered how my summer experience was oddly reminiscent of a similar singular experience that Feynman had had in high school. More about that later. For now I will just say that I only wish the results in my case had been as significant.

It was probably not until graduate school that I fully began to understand the ramifications of what that science teacher had been trying to relate to me, but my fascination with the world of fundamental particles, and the world of this interesting guy Feynman, who wrote about it, began that summer morning in high school and in large part has never stopped. I just remembered, as I was writing this, that I chose to write my senior thesis on path integrals, the subject Feynman pioneered.

Through a simple twist of fate, I was fortunate enough to meet and spend time with Richard Feynman while I was still an undergraduate. At the time I was involved with an organization called the Canadian Undergraduate Physics Association, whose sole purpose was to organize a nationwide conference during which distinguished physicists gave lectures and undergraduates presented results from their summer research projects. It was in 1974, I think, that Feynman had been induced (or seduced, I dont know and shouldnt presume) by the very attractive president of the organization to be the keynote speaker at that years conference in Vancouver. At the meeting I had the temerity to ask him a question after his lecture, and a photographer from a national magazine took a picture of the moment and used the photo, but more important, I had brought my girlfriend along with me, and one thing led to another and Feynman spent much of the weekend hanging out with the two of us in some local bars.

Later, while I was at graduate school at MIT, I heard Feynman lecture several times. Years later still, after I had received my PhD and moved to Harvard, I presented a colloquium at Caltech, and Feynman was in the audience, which was slightly unnerving. He politely asked a question or two and then came up afterward to continue the discussion. I expect he had no memory of our meeting in Vancouver, and I am forever regretful of the fact that I never found out, because while he waited patiently to talk to me, a persistent and rather annoying young assistant professor monopolized the discussion until Feynman finally walked off. I never saw him again, as he died a few years later.

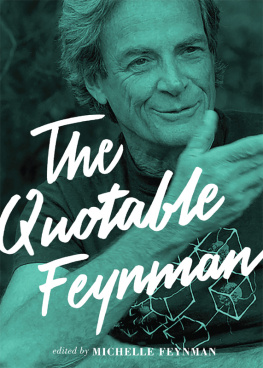

R ICHARD F EYNMAN WAS a legend for a whole generation of physicists long before anyone in the public knew who he was. Getting a Nobel Prize may have put him on the front page of newspapers around the world, but the next day there are new headlines, and any popular name recognition usually lasts about as long as the newspaper itself. Feynmans popular fame thus did not arise from his scientific discoveries, but began through a series of books recounting his personal reminiscences. Feynman the raconteur was every bit as creative and fascinating as Feynman the physicist. Anyone who came into personal contact with him had to be struck immediately by his wealth of charisma. His piercing eyes, impish smile, and New York accent combined to produce the very antithesis of a stereotypical scientist, and his personal fascination with such things as bongo drums and strip bars only added to his mystique.

Next page