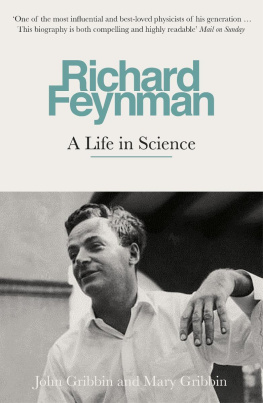

Genius

The Life and Science of Richard Feynman

James Gleick

For my mother and father,Beth and Donen

I was born not knowing

and have only had a little time to change that here andthere.

Richard Feynman

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

FAR ROCKAWAY

Neither Country nor CityA Birth and a Death

Its Worth ItAt SchoolAll Things Are Made ofAtomsA Century of ProgressRichard and JulianMIT

The Best PathSocializing the EngineerTheNewest PhysicsShop MenFeynman of Course IsJewishForces in MoleculesI s He Good Enough?

PRINCETON

A Quaint Ceremonious VillageFolds andRhythmsForward or Backward?The ReasonableManMr. X and the Nature of TimeLeast Action inQuantum MechanicsThe AuraThe White Plague

Preparing for WarThe Manhattan Project

Finishing Up

LOS ALAMOS

The Man Comes In with His BriefcaseChain

ReactionsThe Battleship and the Mosquito Boat

DiffusionComputing by BrainComputing byMachineFenced InThe Last SpringtimeFalseHopesNuclear FearI Will Bide My TimeWeScientists Are Clever

CORNELL

The University at PeacePhenomena Complex

Laws SimpleThey All Seem AshesAround aMental BlockShrinking the InfinitiesDysonAHalf-Assedly Thought-Out Pictorial Semi-VisionThingSchwingers GloryMy Machines Came fromToo Far AwayThere Was Also Presented (byFeynman)Cross-Country with Freeman Dyson

Oppenheimers SurrenderDyson Graphs, FeynmanDiagramsAway to a Fabulous LandCALTECH

Faker from CopacabanaAlas, the Love ofWomen!Onward with PhysicsA Quantum Liquid

New Particles, New LanguageMurrayIn Search ofGeniusWeak InteractionsToward a Domestic Life

From QED to GeneticsGhosts and Worms

Room at the BottomAll His KnowledgeTheExplorers and the TouristsThe Swedish Prize

Quarks and PartonsTeaching the YoungDo You

Think You Can Last On Forever?Surely YoureJoking!A Disaster of TechnologyEPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

A FEYNMAN BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

PROLOGUE

Nothing is certain. This hopeful message went to an Albuquerque sanatorium from the secret world at Los Alamos. We lead a charmed life.

Afterward demons afflicted the bomb makers. J. Robert Oppenheimer made speeches about his shadowed soul, and other physicists began to feel his uneasiness at having handed humanity the power of self-destruction. Richard Feynman, younger and not so responsible, suffered a more private grief. He felt he possessed knowledge that set him alone and apart. It gnawed at him that ordinary people were living their ordinary lives oblivious to the nuclear doom that science had prepared for them. Why build roads and bridges meant to last a century? If only they knew what he knew, they surely would not bother. The war was over, a new era of science was beginning, and he was not at ease.

For a while he could hardly workby day a boyish and excitable professor at Cornel University, by night wild in love, veering from freshman mixers (where women sidled away from this rubber-legged dancer claiming to be a scientist who had made the atomic bomb) to bars and brothels. Meanwhile new col eagues, young physicists and mathematicians of his own age, were seeing him for the first time and forming their quick impressions. Half genius and half buffoon, Freeman Dyson, himself a rising prodigy,

wrote his parents back in England. Feynman struck him as uproariously Americanunbuttoned and burning with physical energy. It took him a while to realize how obsessively his new friend was tunneling into the very bedrock of modern science.

In the spring of 1948, stil in the shadow of the bomb they had made, twenty-seven physicists assembled at a resort hotel in the Pocono Mountains of northern Pennsylvania to confront a crisis in their understanding of the atom. With Oppenheimers help (he was now more than ever their spiritual leader) they had scraped together the thousand-odd dol ars needed to cover their rooms and train fare, along with a smal outlay for liquor. In the annals of science it was the last time but one that such men would meet in such circumstances, without ceremony or publicity. They were indulging a fantasy, that their work could remain a smal , personal, academic enterprise, invisible to most of the public, as it had been a decade before, when a modest building in Copenhagen served as the hub of their science.

They were not yet conscious of how effectively they had persuaded the public and the military to make physics a mission of high technology and expense. This meeting was closed to al but the few invited participants, the elite of physics. No transcript was kept. Next year most of these men would meet once more, hauling their two blackboards and

eighty-two

cocktail

and

brandy

glasses

in

Oppenheimers station wagon, but by then the modern era of physics had begun in earnest, science conducted on a scale the world had not seen, and never again would its

chiefs come together privately, just to work.

The bomb had shown the aptness of physics. The scientists had found enough sinew behind their penciled abstractions to change history. Yet in the cooler days after the wars end, they realized how fragile their theory was.

They thought that quantum mechanics gave a crude, perhaps temporary, but at least workable way to make calculations about light and matter. When pressed, however, the theory gave wrong results. And not merely wrongthey were senseless. Who could love a theory that worked so neatly at first approximation and then, when a scientist tried to make the results more exact, broke down so grotesquely? The Europeans who had invented quantum physics had tried everything they could imagine to shore up the theory, without success.

How were these men to know anything? The mass of the electron? Up for grabs: a quick glance gave a reasonable number, a hard look gave infinitynonsense. The very idea of mass was unsettled: mass was not exactly stuff, but not exactly energy, either. Feynman toyed with an extreme view. On the last page of his tiny olive-green dime-store address book, mostly for phone numbers of women (annotated dancer beauty or call when her nose is notred), he scrawled a near haiku.

Principles

You cant say A is made of B

or vice versa.

Al mass is interaction.

Even when quantum physics worked, in the sense of predicting natures behavior, it left scientists with an uncomfortable blank space where their picture of reality was supposed to be. Some of them, though never Feynman, put their faith in Werner Heisenbergs wistful dictum, The equation knows best. They had little choice.

Next page