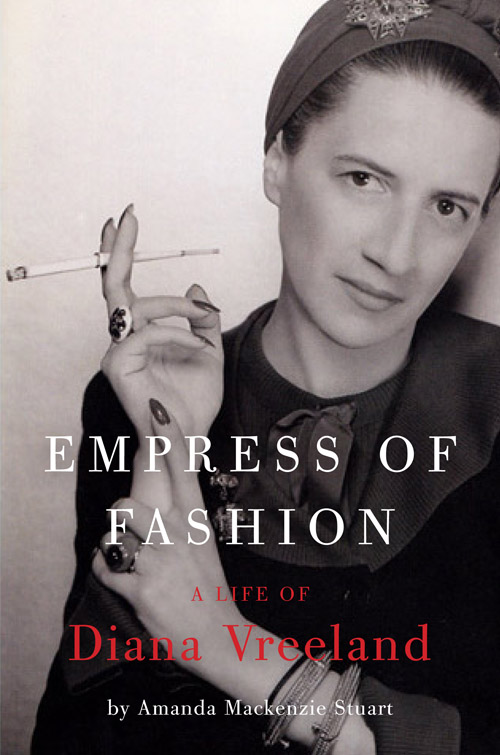

Empress of Fashion

A Life of Diana Vreeland

Amanda Mackenzie Stuart

www.harpercollins.com

To Michael

Contents

My maid here at the Crillon is driving me crazy.... Ive been having fittings in the morning all week long and Betty, my maid, is down on her knees sticking pins in my hembut she wont look in the mirror.

Ah madame, shell say, Quelle belle robe.

Betty, Ill say, Dont look at me, look in the mirror.

Mais madame, comme cest jolie.

Betty! I said, Look in the mirror! What I want is in the mirror. What you want, you cant see because you wont look at it.

D iana Vreeland (190389) believed in the power of the reflected image with something close to religious fervor. She once observed that without a mirror, you lose your face, you lose your self-image. When that is gone, that is hell. Her faith in the magic of the looking glass propelled her through a long life, and into a distinguished career at a time when it was unusual for a woman from her background to work at all. She joined Harpers Bazaar in 1936, officially becoming its fashion editor for twenty-three years from 1939; she was editor in chief of American Vogue from 1963 until 1971; and from 1972 she was special consultant to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where she launched fifteen groundbreaking costume exhibitions. She was regarded, at her peak, as the empress of American fashion, or as one admirer put it: the High Druidess of fashion, the Supreme Pontiff, Perpetual Curate, and Archpresbyter of elegance, the Vicaress of Style. She is thoughtby someto be the cloth from which twenty-first-century editors in chief of fashion magazines are cut.

However, Diana often insisted that she was really an amateur at heart. Her resistance to being defined by her working life was noted by the British photographer Cecil Beaton while she was still at Harpers Bazaar in the 1950s: She is indeed such a powerful personality in her own right, and so little dependent on the fashion world for her terms of appeal, that many of her friends never think of her in connection with printers ink, he wrote. Growing up as cubism emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century, Diana had the appearance of a multifaceted artifact herself, a creature of planes, angles, and polished surfaces, interpretable from multiple viewpoints, frequently in motion and in vivid color. She may have favored her reflection in the mirror; but she was remembered by many in vibrant three-dimensional reality as she erupted into a room. She didnt merely enter a room, she exhilarated it, wrote Nicholas Haslam, who worked in the art department of Vogue in the early 1960s. And all eyes immediately locked on her, hypnotised.... Her actual presence was like a sock on the jaw. You knew you were seeing a supernova.

Her face was the most famous part of her. Mrs. Vreelands head sits independently on top of a narrow neck and smiles at you. Everything about her features is animated by amused interest, wrote Beaton. Provided she was engaged or charmed, the overwhelming impression was of a brilliant glint that spread outward from narrow brown eyes, beneath Vaselined eyelids, across high cheekbones exaggerated with great streaks of rouge, with which she also powdered her ears, turning them a shade of terra-cotta. The centerpiece of this face was a very large beaky nose above a huge, wide crimson mouth and a pointed aggressive jaw. The effect was framed by jet black hair, sometimes in a snood, veneered into place from her hairline with such a high metallic sheen that it is said to have clinked when a waiter bumped it with a tin tray. Beneath her head Diana maintained the slender, supple body of a dancer until the end of her life, but she held it in a curious sloping posture. When she moved, her pelvis thrust forward and her upper body sloped backward as she glided ahead. Once she gained momentum she assumed the lolloping gait of a dromedary, topped with a light sashay, a walk she said she copied from the showgirls of the Ziegfeld Follies . Even when seated she was animated: jabbing, pointing, prodding, and kneading the air, the fingers of one hand spread outward, a cigarette clasped in the other, displaying to advantage long, red, perfectly manicured talons. Like everyone else, I was not introduced to her but to her index finger, extended as a kind of barrier to trade, wrote Jonathan Lieberson, who met her in the 1960s when Diana was in her sixties too. She was improbable in the extreme: a strange figure, sitting closed cross-legged, with erect spine, stroking the arch of an extended foot, her fingers stretching... her mouth and out-thrust jaw in constant motion.

Those trying to describe her often reached for avian imagery. An authoritative crane, said Cecil Beaton. Some extraordinary parrota wild thing thats flung itself out of the jungle, thought Truman Capote. An Aztec bird woman, suggested Vogue feature writer Polly Devlin, though she also proposed a Kabuki runaway. Dianas appearance could cause confusion. On a trip to Kyoto, it was said that her Japanese hairdressers thought she was a man before they decided she was Chinese. (As you know, thats not the most popular thing you can be in Japan... but they were very polite. And once you get a person totally wet with half their make-up off, you see something.) It is less often remarked that Diana Vreeland was actually ugly, an ugliness made worse by having mild astigmatism which could make her squint. Polly Devlin was forcefully struck by Dianas unattractiveness on their first meeting, and equally amazed by how quickly the ugliness seemed to melt away. Theres a word not much used nowadays, limned, which is to illuminate, to edge in color, she wrote. She was always limned, set in shock against her background.

One reason Diana had such a mesmerizing effect was the sound, as well as the sight, of her. When she laughed, she slowly and deliberately intoned each ha of ha-ha-ha, much, I imagined, as one of the denizens of Hogarths Gin Lane might have done, wrote Lieberson. Bystanders were rooted to the spot by the peculiar swooping cadences of her gravelly bass voice, which could rise to a booming bark and fall back down to a whisper in the course of one sentence, its colors darkened by years of smoking. The rhythm of her speech was unpredictably emphatic, punctuated by the throaty laugh, a descending scale that went M-m-m , and (since she took a positive view), the word duh-vine. She could generally be relied on to light upon at least one italicized word every few seconds, more often when telling a story. She had a predilection for rolling her r s as in rrr ighto; and faux French pronunciation, so that corduroy became cord-du- roi , tiger became tee -gray, and video was pronounced as in Montevideo. Though she could bridle (or worse) at unrefined language, she had an acute ear for gamey slang and reminded Beaton of Falstaff, a very different physical type. But even her manner of speech was less interesting than what she actually said.

By the time she joined Harpers Bazaar , Diana had cultivated a verbal brilliance that was all her own, her talk interspersed with Delphic remarks that were captured by listeners like butterflies, only to flutter weakly on the page. Pink is the navy blue of India was one much-quoted aperu with which she became bored. Blue jeans are the most beautiful thing since the gondola, was another, and there were thousands more in the manner of One thing I hold against Americans is that they have no flair for the rain. They seem unsettled by it; its against them: they take it as an assault. She attributed her oblique point of view to the astigmatism: