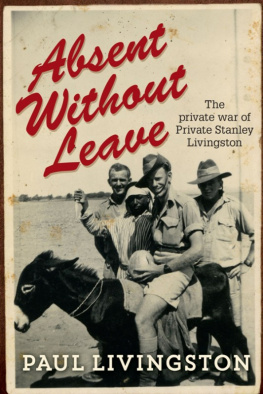

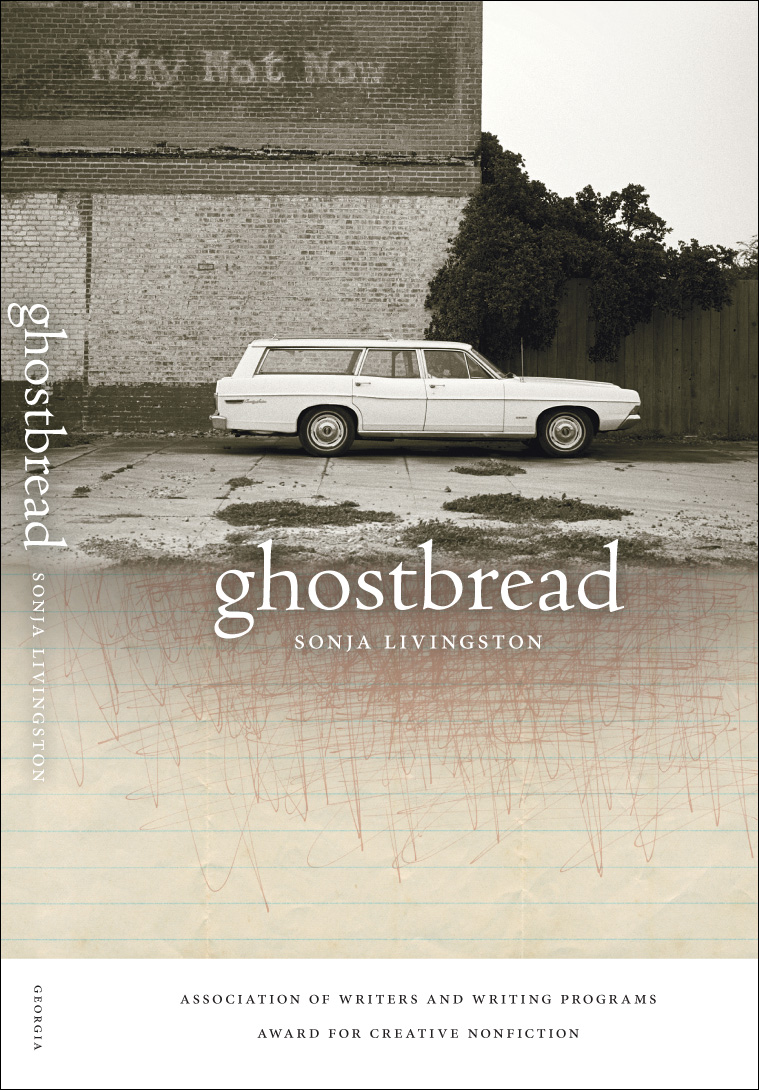

ghostbreadWINNER OF

THE ASSOCIATION

OF WRITERS

AND WRITING

PROGRAMS AWARD

FOR CREATIVE

NONFICTION

ghostbread

SONJA LIVINGSTON

Paperback edition published in 2010 by

The University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2009 by Sonja Livingston

All rights reserved

Designed by Walton Harris

Set in 10/14 Garamond Premier Pro

Printed digitally in the United States of America

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover

edition of this book as follows:

Livingston, Sonja.

Ghostbread / Sonja Livingston.

ix, 239 p.; 23 cm.(Association of Writers and Writing

Programs Award for Creative Nonfiction)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-3398-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-3398-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Livingston, SonjaChildhood and youth. 2. Poor girls

New York (State)Biography. I. Title.

HQ777.l58 2009

305.23092dc22

[B] 2009009150

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-3687-9

ISBN-10: 0-8203-3687-4

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

This is a work of literary nonfiction, based on experience and memory. Only names have been purposefully changed, and then in deference to those whose lives intersected with my own.

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-3750-0

To SONJA MARIE ROSARIO

and all the girls of Rochester, Buffalo,

and places in between

preface

When you pick up a pen, put it to paper, and let yourself go, certain words throw themselves at you, whole paragraphs come to you unbidden, entire passages stake their claim, refuse to be ignored. Even when you dont want them. Especially when you dont want them.

As a girl, I never talked about how I grew up. It was complicated. People might point fingers. My face might turn hot and wet and a hundred shades of red. Mostly, I was certain that I was alone in a way that no one would understand.

But as I sat in my first creative writing class, wadding up paper and waiting for something to come, the stories nudged at me, harder and harder, until finally, they made their way out.

I began to write. Of seven children who followed a mother as she flew around western New York like a misguided bird. How they flew and flew until they were sick from all the flying then landed flat and broken into the muggy slums of Rochester, New York. I wrote of living in apartments and tents and motel rooms. Of places where corn and cabbage grew in great swaths. Of the Iroquois on their reservation outside of Buffalo. About sleeping in shacks and cars and other peoples beds, and finally about a tiny dead end street in an overcrowded innercity neighborhood.

And as I began to share my writing, I learned that I was not so alone. While the specifics of my circumstances were certainly unusual, a child living without basic resources in 1970s America was not as uncommon as Id once believed.

The western portion of New York State is a coming-together of various influences. The northern tip of Appalachia meets up with the easternmost notch in the Rust Belt. Poverty exists in many forms within a two-hundred-mile radius. It blooms quietly on Indian reservations, in old farm towns, and in cities seething with higher rates of crime and child poverty than New York City. It spreads like a bruise between Buffalo and Rochester, a stain just under the skin.

Writing helped me to talk about the places and people of my childhood and to connect with others, but in sharing, I inevitably encounter someone who does not believe.

Rochester has no ghetto, they say, or else they cock an eyebrow and say, Reservations? So near us?

So well get into a car and drive out to a place, only to find that what was once barely standing has finally collapsed. Where for hundreds of years stood a behemoth of a house are now only trees. The old shack that once gave shelter to a brood of children has become vines. The gold-shingled two-story with a gangly lilac out back is just another vacant city lot. And though I cant always recover the specifics (the houses or gardens or trees) of the past, the reality of such existence remains.

Its there. For those who steer their cars off the New York State Thruway and interstates. The broken cities, the sprawling rusted landscapes, the huddled people.

They are all there.

I wrote this book because the pain and power and beauty of childhood inspire me. I wrote it selfishly, to make sense of chaos. I wrote it unselfishly, to bear witness. For houses and gardens and children most of us never see.

acknowledgments

Earlier versions of some material appeared as essays in the Iowa Review, Gulf Coast, Puerto del Sol, and Mary.

Many thanks to early readers of my work: Judith Kitchen, Karen DeLaney, Sarah Freligh, Paul Bond, Deb Wolkenberg, Sharon Pierce, and the Hilton HC (Laurie, Bonnie, Donna, Karen R., and Karen K.). I appreciate careful readings by Deanna Ferguson, Allen Galante, Gregory Gerard, Stephen Kuusisto, and Julietta Wolf-Foster. I am grateful to Gail Mott for her thorough reading, and to her and Peter Mott for so much more.

Thanks to my angels from New Orleans, especially Amanda and Joseph Boyden, Dinty W. Moore, Lisa Shillingburg, and Kim Bradley.

Rob McQuilkin, with his sharp eye and quick pen, greatly improved this manuscript and championed it against even greater odds.

Thank you to Kathleen Norris, AWP, and the University of Georgia Press, to family and friends, and most of all, to those represented in these pages.

Much love to Jim.

part one the get go

I know where I came from.

It must have been April or May of 1967 when he came through town, a vacuum-cleaner salesman with a carload of rubber belts, metal tubing, and suction hoses. Spring in western New York, it was probably a sunless dayhe may have been chilled as he grabbed hold of his Kirby upright, walked to the door, and rang the bell.

She was a well-formed redhead with a dry-cleaning job and a house full of children to forget. She must have put hand to hip, flashed falsely shy eyes, and said something about not needing another vacuum.

He had full lips, and used them to throw a smile in her direction. And she, who was partial to full-lipped smiles, let him in.

He rang; she answered. She was hungry; he had a bit of sugar on his finger. He was tired; she provided a pillow for his head. Soft. Sweet. Easy.

Sometimes its just that simple.

I was late. Born in the wrong year, according to my mother. Though scheduled to clear her womb in 1967, I was mule-headed and did not exit my mothers body until late January 1968.

The story was a good one. My mother swore by it. People clucked and laughed when she told it. Growing up, it made my birth seem special. Like I was cracked from another of Adams ribs or crawled from my mothers womb fully-formed and armored, like some commonplace Athena.