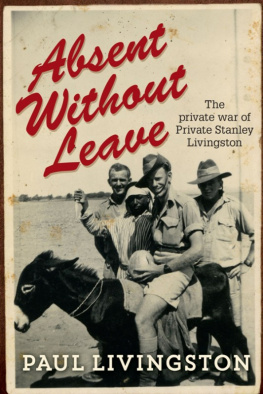

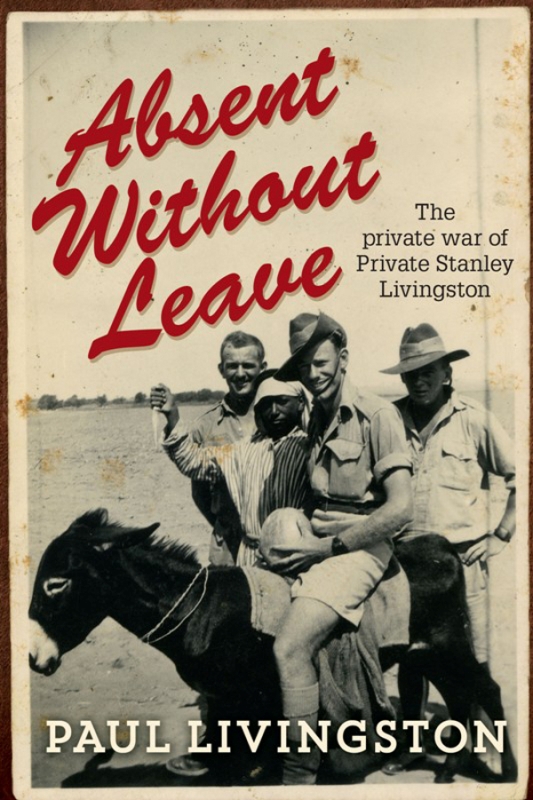

Absent Without Leave follows three wide-eyed young Australian men from their enlistment at the Sydney Showground in 1940 to the war in the Middle East and jungle warfare in the Asia-Pacific. Private Stanley Livingston and his two best mates, Roy Lonsdale and Gordon Oxman, would be brothers-in-law as well as brothers in arms by the end of the war, as Stanley would marry Roys sister Evelyn, while Gordon would marry Lilly Livingston, Stanleys younger sister.

In this case the term absent without leave has no negative connotation. Between their Middle East and Pacific campaigns Privates Livingston and Oxman, and many of their fellow soldiers, abandoned their units to be with their loved ones. These men were not running from battle or responsibility, but to the service of their families who desperately needed them.

This is also an account of the civilian men and women back home, and of Stanleys future wife, Evelyn. Evelyns war is a story in itself, by day riveting bombers at Kingsford Smith Airport, by night enjoying the spoils of war courtesy of the ever-present and exotic American servicemen.

Absent Without Leave gives a deeply human face to the circumstances of war. Like many veterans, Stanley Livingston spoke little about the war, and this book is an attempt by his son to discover the man he had never really known. The result is an extraordinary story about an ordinary man: illuminating, deeply moving and told with no shortage of humour. Absent Without Leave unearths a part of Australian history that has largely been forgotten, because no-one ever really talked about it. Until now.

The private war of

Private Stanley Livingston

PAUL LIVINGSTON

First published in 2013

Copyright Paul Livingston 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 582 8

eISBN 978 1 74343 346 1

Cover design by Lisa White

Set in 12.5/17 pt Minion by Midland Typesetters, Australia

For Dottie

Contents

Ever heard the one about the old digger who never talked about the war? So have II grew up with one. As a child it never occurred to me to ask, And how was your war, Dad? I took my fathers war for granted. His years as a front-line soldier didnt seem to have left any obvious scars. Curiosity came only after I vacated the nest. On my irregular sorties to the suburbs Id sit in the backyard with the old man, an Onkaparinga blanket covering the Hills Hoist to keep the sun off. To keep the sun off the beer, that is. We talked, one on one; I was eager for anecdotes. I was twenty-nine and in my first year of what some might laughingly describe as a career in stand-up comedy. War is no laughing matter. But then again, you had to be there. Stanley J. Livingston had been there.

I only managed to glean the barest hints of my fathers experiences in World War II (Ive always found the habit of numbering wars unnerving: it implies a certain inevitability, and there are still a lot of numbers out there to get through). Stanley didnt live to tell the full tale. By wandering through my own memories, as well as those of people who knew him and many more who didnt, I wondered if I might catch a glimpse of the man I never knew.

Introduction

Two of the boys, a wog, a donkey and myself

One of the most enduring images from Australias ill-fated campaign in Gallipoli is that of John Simpson Kirkpatrick, the man with the donkey. Legend has it that after working as a merchant seaman for four years, Simpson enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in September 1914. He was assigned to serve with the 3rd Field Ambulance as a stretcher-bearer, but Simpson shunned the stretchers in favour of a donkey called Murphy, the animal he employed to transport wounded men to the beach at Anzac Cove. In what is claimed were lightning dashes into no-mans-land, he is rumoured to have saved the lives of over three hundred men before being killed in action on 19 May 1915. A hush fell over the Gallipoli Peninsula on the day the man with the donkey was slain.

Or so the story goes.

Almost a century after the events of Gallipoli, the mythos of Simpson continues. The tale has crossed continents as accounts of Simpsons feats have been told again and again. Some have Simpson as something of a saintly figure, others a bacchanalian brawler; there are even claims that Simpson was shot by an Australian. What does all this really have to do with young Jack Simpson? Does the elevation of a good man into a superhero enhance or offend his memory? Does it matter? One thing is certainthe legend wasnt Simpsons doing. It was born after his death, the yarn spun and woven through the decades. There can be no denying the appeal of such a myth. The Simpson legend has all the necessary ingredients: heroism, anti-authoritarianism, selflessness, larrikinism and mateship. Throw in a faithful little donkey named Murphy (or Abdul or Duffy, depending on the source), and a legend is born.

The lowly donkey, along with its companions the ass and the mule, has been exploited in more than one famous myth. The Bible is full of donkeys, from the one who spoke to BalaamAm I not your donkey on which you have ridden, ever since I became yours, to this day? (Numbers 22:30)to the animals more significant role in the New Testament: Mary, pregnant with Jesus, is said to have travelled to Bethlehem on a small donkey, and just before his own death, Marys firstborn himself rode one into Jerusalem. The donkey has since been dubbed the Christ-bearer. The story of stretcher-bearer Simpson trading his stretcher for a donkey has some resonance with the Jesus myth: the humble Christ, renowned for helping the sick and broken with no shortage of courage or humility, before entering the arena of his own death. A single image can wield enormous power. After decades or even centuries, a myth may bear little witness to the actualities of its origin. Perhaps this is of small consequence, especially if the myth promotes qualities beneficial to its devotees.

Whether Stanley James Livingston, a private in the 2/17th Australian Infantry Battalion, was mocking Simpson when he climbed aboard a donkey somewhere in the Middle East is not clear. World War I was coming to a close when Stanley was un-immaculately conceived in the year of our donkey-straddling Lord one thousand nine hundred and eighteen, and by the time the photo was snapped the myth was already well and truly ingrained. Perhaps it was the biblical myth that Pte Livingston had in mind? There is every chance he was in the vicinity of Jerusalem at the time. But precisely where and when the photo was taken is not so clear. Does this look like the fresh face of a young man enjoying his first overseas trip, a battle virgin? Or are we looking at a war-weary veteran of one of the most intense and bloody campaigns in military history? What had he got himself into, this kid from suburban Zetland, in the middle of no-mans-land, with, as he put it, two of the boys, a wog, a donkey and myself ?

Next page