Coal to Diamonds is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some of the names and personal characteristics of the individuals involved have been changed in order to disguise their identities. Any resulting resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

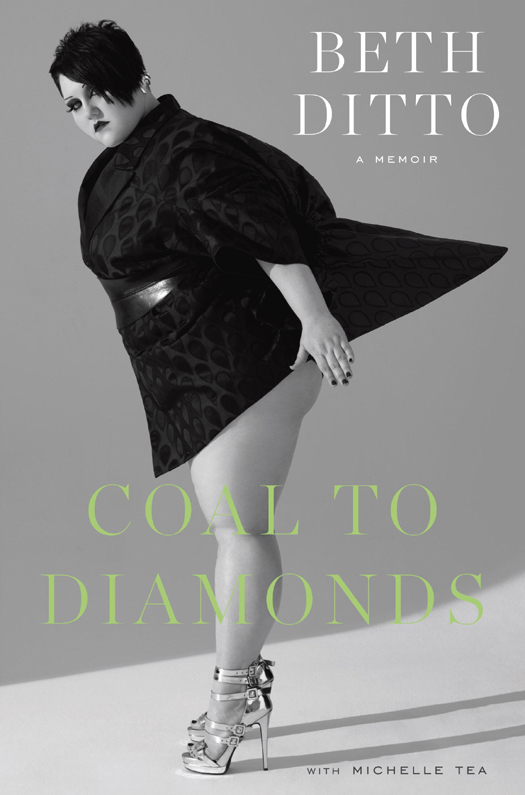

Copyright 2012 by Beth Ditto

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

S PIEGEL & G RAU and Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ditto, Beth.

Coal to diamonds: a memoir/Beth Ditto; with Michelle Tea.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-385-52974-7

1. Ditto, Beth. 2. Punk rock musiciansUnited StatesBiography. 3. Lesbian musiciansUnited StatesBiography.

I. Tea, Michelle. II. Title.

ML420.D5665A3 2012

782.42166092dc22 2009051672

[B]

www.spiegelandgrau.com

Jacket design: Greg Mollica

Jacket photograph: Josh van Gelder/Camera Press/Redux

v3.1

Dedicated to my two families: the family I was born into and the family I chose. You all give me a purpose, a history, and a future. You all keep me driven, inspired, and laughing. I never meant any of these stories to put anyone in a bad light; they are all true, some painful. Without all the stories, the best ones and the worst ones, I wouldnt be who I am now. Im proud of myselfsomething I can say because of all the people in this book.

In memory of my dad,

Homer Edward Ditto

19542011

Contents

1

There was a time when Judsonia, Arkansas, was a booming metropolis keeping pace with the rest of the country. The people were hopefulworking, shopping, and living life. A womens college was teaching ladies, and the town cemetery kept a plot for fallen Union soldiers right smack in the middle of all the dead Confederates.

That was back in the 1940s. Then in 52 a tornado swirled in and tore the whole place down, leaving a dusty depression in its wake. After that, time got sticky while the people got slower and stayed that way. Since then, Judsonia just hasnt moved on the way the rest of the country has.

At thirteen years old, I was hanging out one afternoon in a pair of sweats and a hand-painted T-shirt, bumming around a mostly empty house. It was the early 90s, but there, in Judsonia, it might as well have been the 80s, or the 70s. I, Mary Beth Ditto, did not go to school that day. I stayed at home to laze around the housea house that was normally crawling with way too many kids and a sick aunt, but which was miraculously empty that day, totally peaceful. Just because I played hooky, dont go getting the idea that I was a bad kid. I wasnt, but I wasnt a good kid either. I wasnt a nerdy square turning in homework on time and kissing my teachers butt, and I certainly wasnt some juvenile delinquent ducking class to hunt down trouble. I just wanted to see what that big, hectic house would feel like full of unusual quiet.

My three little cousins were off at school. Because they had the misfortune of being born to the worlds shittiest mom, those three cousinswho all had names that began with Ahad come to live with Aunt Jannie. When social services had finally been called for the fourth time, the social workers poked around to see if those three little As had any family who could take them in, and when they found Aunt Jannie she, of course, said yes.

The As made their beds on couches and chairs at Aunt Jannies, crawling next to one another in the night, hunkering down wherever there was space and warmth to snuggle into. Their arrival in Aunt Jannies home was part of a grand tradition in my family. In a family so large that it tumbled and stretched to the edges of comprehension, every one of us came knocking on Aunt Jannie and Uncle Artuss front door eventually, looking for refuge. Something always pushed us there. For the As it was their drunken, neglectful mother. For me it was my violent stepfather. For my mother it was her sexually abusive father. And there were countless other short-term squatters, like my cousins whose mother shot her husband in the head. Children came and children went as circumstance and tragedy dictated. Aunt Jannie just couldnt turn away a kid with nowhere to go, not even when her diabetes made her so slowed-down and sickly.

Aunt Jannie took people in for so many years that her house probably wouldve felt empty without stray bodies on every spare bit of furniture. Jannies hearther original heartwas a good and giving thing, even though her life had fossilized pain around the outside. Deep inside, Jannie was secretly warm and caring, and that was the place that made her take in any person who was going through a tough time in life. She never sat down and calculated the costs of being the whole towns savior. Her impulse to help, plus the whole towns expectation that she would open her doors, and everyone loving her for doing it, meant that, eventually, Aunt Jannie just couldnt say no to anyone. Even when maybe she should have. When she was at the end of her mental rope, Aunt Jannie probably needed someone to reach out and give her a hand, but I dont know how she couldve asked for that when she was the one always giving it.

Aunt Jannies daughtermy Aunt Jane Annlived in that big house too. Jane Ann was young enough to feel like a sister but old enough to take me to a Rolling Stones concert. Her teenage son, Dean, was the unofficial king of the house. While the rest of us lived like forest creatures, constantly looking for a nice space to burrow in, Dean got his very own bedroom. His own bedroom! I couldnt comprehend the luxury. Like some put-upon fairy-tale princess I earned my place keeping the As in line and tending to Aunt Jannies slow-motion suicidefixing her the pitchers of Crystal Light that had her as addicted as the five packs of full-flavor Winstons she smoked her way through each day. That was taking care of Aunt Jannie: tearing open packets of the fake-flavor tea and inhaling the lemony aspartame powder till my nose was crusted with it, then bringing it to the kitchen table, where she lit her Winstons one from another. There was always something smoldering in the ashtray. I would sit in the cigarette haze and listen to her talk about the old times in Judsonia. Truth be told, being an audience for Aunt Jannies crazy tales was my real task; they could snag my imagination better than television. I would listen, wide-eyed, to her outlandish stories, like the ones about her running from her wheelchair-bound mother as a little girl and climbing up on the furniture so that poor woman, who was crippled from polio, couldnt grab her. Aunt Jannie was a spitfire Scorpio. She used to sneak down to the river, to a chained-up shed that hid a forbidden jukebox. Judsonia didnt allow dancing, so Aunt Jannie, thirteen years old and full of pent-up fire and life, would sneak into the woods with other barely teenage rebels, and together theyd dance, getting drunk on home-brewed liquor and twirling away the night.

That teenage Aunt Jannie felt her culture pushing down on her, and so she pushed back with the shove of her whole body twisting to the beat. In between segments of