ACCLAIM FOR Jorge G. Castaedas

Compaero

Brilliant rich in narrative detail.

The Christian Science Monitor

Brilliant research [reveals] the last myth of 20th-century revolution.

Washington Post Book Review

Analyzes Guevara and his legacy with the clarity and insight that have earned [Castaeda] his place as one of Mexicos most distinguished political scientists.

The New York Times Book Review

Astute a gripping tale of a man bent on martyrdom.

The Boston Globe

Carefully documented and critical [and it] reads like a thriller.

Wall Street Journal

[Castaedas] powerful intellect aims at uncovering the roots and development of Ches thinking.

The New York Times

Also by Jorge G. Castaeda

Utopia Unarmed

Limits to Friendship

(with Robert Pastor)

The Mexican Shock

Jorge G. Castaeda

Compaero

Jorge G. Castaeda was born and raised in Mexico City. He received his B.A. from Princeton University and his Ph.D. from the University of Paris. He has been a professor of political science at the National Autonomous University of Mexico since 1978. He has also been a senior associate of the Carnegie Institute for International Peace in Washington, D.C., and a visiting professor at Princeton University and the University of California at Berkeley. In 1997 he began a long-term, half-time appointment as Professor of Political Science and Latin American Studies at New York University. He is a regular columnist for the Los Angeles Times, Newsweek International, and the Mexican weekly Proceso.

For Jorge Andrs

who was born in another time

and will live a better life

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2 Years of Love and Indifference in Buenos Aires:

Medical School, Pern, and Chichina

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6 The Brain of the Revolution; the Scion of

the Soviet Union

Chapter 7 Socialism Must Live, It Isnt Worth Dying

Beautifully.

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 11

16 pages of photographs will be found following page 268

Acknowledgments

This book owes a great deal to many people, but most of all to Miriam Morales, who read it, reread it, and put up with it (and me) endlessly. To her my thanks, as well as to Maria Caldelari, Georgina Lagos, Cassio Luiselli, Joel Ortega, Alan Riding, and my friend and editor at Knopf, Ash Green, who all read the manuscript in its entirety and are responsible for any improvements it may have undergone.

I am also particularly grateful to the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Endowment at Dartmouth College, where I carried out part of the research for the book; Marisa Navarro, Barbara Gerstner, Lou Anne Cain, and Luis Villar at the Dartmouth College library were extremely generous with their support, time, and patience. I also wish to thank Marisela Aguilar, Lisa Antilln, Carlos Enrique Daz, Aleph Henestrosa, Silvia Kroyer, Marcelo Monges, Marina Palta, Christian Roa, Tamara Rozental, and John Wilson at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library at the University of Texas in Austin, for their invaluable help in researching the material for the book.

Many friends in many places provided precious help in obtaining access to interviews, archives, or documents: Gerardo Bracho, Zarina Martnez-Boerresen, Arturo Trejo, and Abelardo Trevio in Moscow, Juan Jos Bremer and Adriana Valads in Germany, Miguel Daz Reynoso in Havana, Jorge Roco in Mexico, Sergio Antelo and Carlos Soria in Bolivia, Alex Anderson and Dudley Ankerson in England, Rogelio Garca Lupo and Felisa Pinto in Argentina, Leandro Katz in New York, Jules Grard-Libois in Brussels, Anne-Marie Mergier in France, and Carlos Franqui in Puerto Rico. I am particularly indebted to Kate Doyle and Peter Kornbluh at the National Security Archive in Washington, D.C., for their constant support in obtaining documents from the U.S. government. I must also acknowledge and be thankful for Jennifer Bernsteins infinite patience and help at Knopf in getting the manuscript into shape.

Finally, a special word of thanks to Homero Campa, Rgis Debray, Chichina Ferreyra, Enrique Hett, James Lemoyne, Dolores Moyano, Jess Parra, Susana Pravaz-Baln, Andrs Rozental, and Paco Ignacio Taibo II. Each in their way made a very special contribution to this book. I am deeply indebted to them. And lastly, my warmest appreciation to Marina Castaeda, who not only did a splendid job of translating and editing from the Spanish, but did so at breakneck speed and, moreover, under extreme, often irrational, and always irritating pressure from her brother the author, or the author her brother.

J.G.C.

Prologue

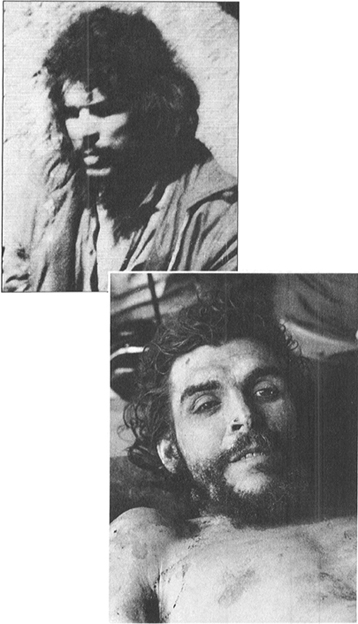

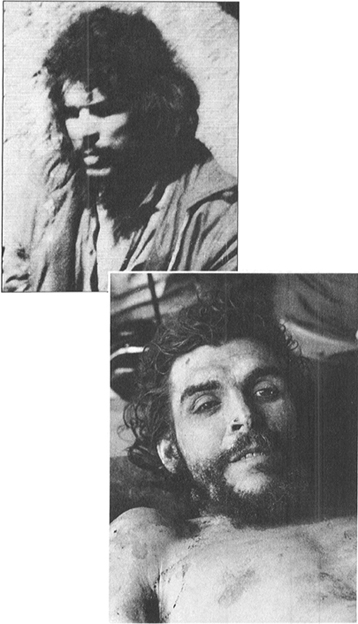

They uncovered his face, now clear and serene, and bared the chest wracked by forty years of asthma and months of hunger in the wilds of the Bolivian southeast. Then they laid him out in the laundry room at the hospital of Nuestra Seora de Malta, raising his head so all could look upon the fallen prey. As they placed him on the concrete slab, they undid the ropes used to tie his hands during the helicopter trip from La Higuera, and asked the nurse to wash him, comb his hair, and trim the sparse beard. By the time journalists and curious townspeople began to file past, the metamorphosis was complete: the dejected, angry, and disheveled man of the day before was now the Christ of Vallegrande, reflecting in his limpid, open eyes the tender calm of an accepted sacrifice. The Bolivian army had made its only field error after capturing its greatest war trophy. It had transformed the resigned and cornered revolutionary, the defeated fugitive from the Yuro ravine, face shadowed by fury and frustration, into the magical image of life beyond death. His executioners had bestowed a human face upon the myth that would circle the world.

Whoever examines these photographs will wonder how the despondent Guevara at the little school of La Higuera was transfigured into the beatific icon of Vallegrande, captured for posterity by the masterful lens of Freddy Alborta. The secret is simple, as General Gary Prado Salmn, Ches captor and the most lucid and professional of his pursuers, explains: