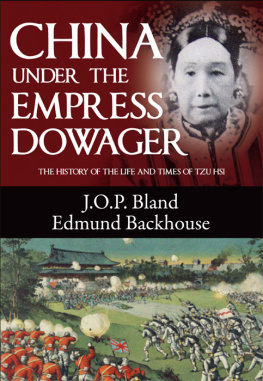

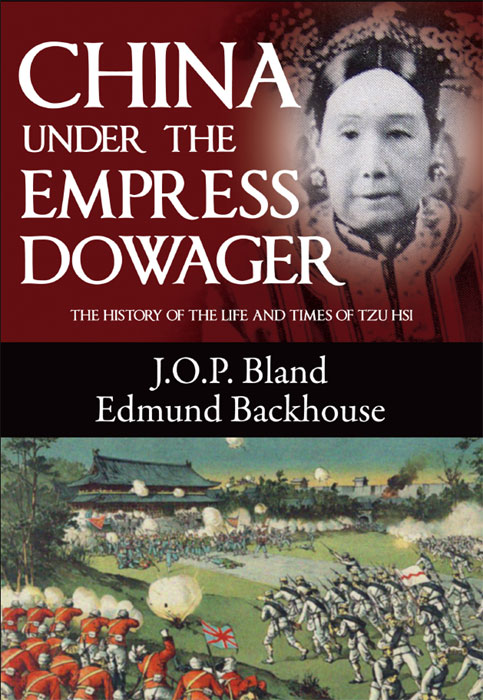

China under the Empress Dowager

By J.O.P. Bland & Sir Edmund Backhouse

ISBN-13: 978-988-18667-4-5

Edition copyright 2010 Earnshaw Books.

China Under the Empress Dowager was first published in 1910.

This edition with a new foreword is reprinted by

China Economic Review Publishing (HK) Limited for Earnshaw Books, Hong Kong

First printing March 2010

Second printing November 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher.

FOREWORD

B Y D EREK S ANDHAUS

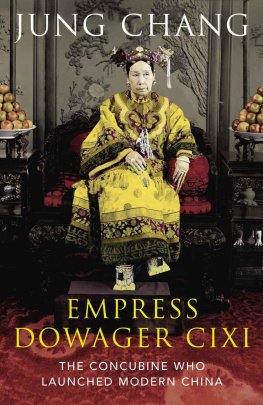

RARELY has a book on Chinese history captured the popular imagination like J.O.P Bland and Edmund Backhouses China under the Empress Dowager. This unique look inside the scintillating and treacherous court life of Chinas last great despot, the Empress Dowager Cixi, appeared at just the right moment in history. In 1910, ten years after the Boxer Rebellion and two years after the death of Cixi, the Chinese Empire was on the verge of collapse and all eyes were on China. At a time when readers were hungry for news of the Middle Kingdom, this book gave them all that and more, providing a fresh perspective on Chinas previous fifty years with thrilling anecdotes from the court and newly translated first-hand accounts. Most amazing of all, the book featured the never-before-seen diary of a well-connected Manchu official, Ching Shan, providing an insiders perspective on the mysterious machinations of the court during the Boxer Rebellion.

But the story behind the book is equally captivating. John Otway Percy Bland, at the time of publication the more famous of the two authors, arrived in Shanghai in 1883. The Irish scholar had been recruited directly from Trinity College to work in the Imperial Maritime Customs Service under Sir Robert Hart, a position he held until 1896. During this time he rose to official rank in the Chinese government, gained fluency in the Chinese language and amassed a wealth of powerful connections. In 1897, now a member of Shanghais Municipal Council, he accepted the position of Shanghai correspondent for The Times of London, and it was in this capacity that he came in contact with a rising star of Chinese scholarship, Edmund Trelawny Backhouse.

Backhouse was, by many accounts, a thoroughly strange yet endearing personality. He had arrived in Peking in 1898 as an Oxford dropout with a knack for languages. He chose to live outside of the foreign compound among the Chinese, shunning the company of other Europeans but allegedly amassing powerful Chinese and Manchu contacts. Within a year of arrival, he had become one of the most respected translators and informants in China, counting among his patrons the British Foreign Service, the Imperial Maritimes Customs Service and Dr. G.E. Morrison, the Peking correspondent of The Times. In 1899, Morrison introduced the two authors, sending a dog-bite wounded Backhouse to stay with Bland while seeking medical attention in Shanghai.

The two men hit it off right away. At first glance Bland, the outgoing sportsman, and Backhouse, the introverted scholar, were an odd pair, but they had much in common. Both shared a deeply rooted respect for their adopted country and its people, and sought to correct Western misconceptions of China. Morrison, meanwhile, spoke no Chinese and had an unflinchingly colonialist outlook which they both despised. Their mutual disdain for the Australian Anglophile provided another strand to their friendship.

In November 1908, Bland was covering all of China for The Times while Morrison was on vacation, and was consequently handed the biggest story of his career: the deaths of both the Empress and Emperor within a day of each other. At a bit of a loss, he turned to the well-informed Backhouse for assistance. Backhouse was able to provide all of the raw material and relevant cultural context for the obituary, while Bland was able to lend structure and a more polished style. The article was a great success, and shortly afterwards Bland suggested the pair compile a full-blown biography of Cixi along the same lines. Backhouse happily agreed and suggested including among other materials the diary of Ching Shan, which he claimed to have found while living in the deceased officials house following the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion. Bland was understandably excited by the revelation and decided to make the diary a centerpiece of the work.

In 1910, China under the Empress Dowager was released to near universal acclaim. Probably no such collection of Chinese documents has ever before been given to the world, or one that better reflects the realities of Chinese official life, wrote Sidney Coryn of The New York Times. To the delight and surprise of its publishers, the book went through nine years on the market. The Ching Shan diary was donated to the British Museum for posterity and, four years later, the two authors followed up with another highly-regarded work, Memoirs and Annals of the Court of Peking.

But China Under the Empress Dowager was not without its detractors. The most outspoken in the early years was Bland and Backhouses colleague-turned-rival, G.E. Morrison, who charged that the Ching Shan diary was a fake. Two of the most prominent sinologists of the day, Sir Reginald Johnson and J.J.L. Duyvendak, studied and attested to the diarys authenticity, and Morrison was written off as a jealous instigator. About 25 years later, Shanghai-based journalist William Lewisohn again challenged the diarys veracity and submitted his findings to Duyvendak, who reexamined the diary and this time around concluded that it was indeed a forgery, though a masterful one in its complexity. Why any one should have taken all this immense trouble, wrote Duyvendek, is more than I can understand.

Though Backhouse, the linguist, was the obvious candidate for the forgery, most people during his lifetime chose to believe that he was the victim of an elaborate Chinese hoax. In the 1970s, Backhouse biographer Hugh Trevor-Roper reached a different conclusion. He traced a pattern of hucksterism throughout Backhouses life, culminating in an outrageous autobiography in which Backhouse claimed to have been the Empress Dowagers long-time lover. Backhouse having been branded as being pathologically compelled to deceive, China under the Empress Dowagers credibility as an historical document all but evaporated.

But it would be a grave error to overlook this most remarkable work on account of one suspect chapter. China under the Empress Dowager was, after all, one of the first books that attempted to portray the Chinese people and their leaders as something more than an amalgamation of clichs and stereotypes. At a time when, just like today, the outside world desperately wanted to know more about China and the Chinese, so much of the existing literature was founded in gross misunderstanding and racially-based fears of the Yellow Peril. China under the Empress Dowager was one of the first books that sought to present a truly sympathetic portrayal of China. It might sound trite today, but the notion that the Chinese were people with similar wants and ambitions was groundbreaking in the days of spheres of influence and White Mans burden.

In this book, Backhouse and Bland succeeded in painting a nuanced picture of the Chinese as few had done before them because they truly knew the country and its people. Using this knowledge, they were able to breathe a degree of clarity and understanding into the complex processes that had mystified the aloof Peking diplomats and the world at large. They were masters at using even the most mundane details to illustrate the infinite complexities and competing interests of the Qing court. Chapter VII, A Question of Etiquette, for example, is a marvelous examination of the superficially simple question of whether foreigners should be exempt from kneeling when granted an official audience. Chinese attitudes of cultural superiority, the need to preserve long-standing tradition, and how to save face before a more powerful enemy all come to the surface in brilliant clarity.