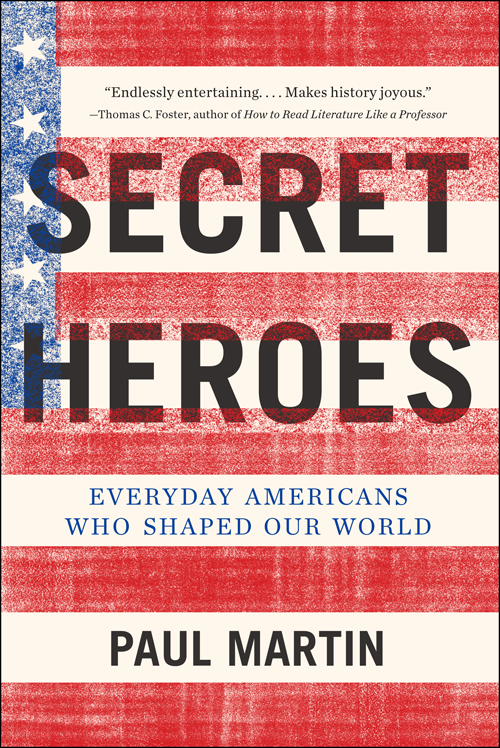

Secret Heroes

Everyday Americans Who Shaped Our World

Paul Martin

For Janice, Evan, and Judy

Contents

T his book is about the accomplishments of a remarkable group of Americansheroes all in different ways, although their names are largely unfamiliar. They represent a wide range of backgroundsscientists, soldiers, spies, adventurers, inventors, businessmen, artists, activists. Among them are individuals from the earliest years of our country right up to modern times. What all these people have in commonother than an outsize measure of courage and determinationare their enduring legacies. Their achievements, though often overlooked, helped shape the world we know today.

A few of these secret heroes radically altered history, such as the Nebraska-born agronomist who saved millions in Asia from starvation through his plant-breeding experiments. Others had less dramatic though no less exceptional attainments, including the travel writer and Japanophile who struck upon the felicitous notion of gracing our nations capital with flowering cherry trees. Despite their obscurity, such deeds are worth remembering.

To help me unearth these thirty uncommon characters, I solicited recommendations from every state historical society, along with more than a hundred history professors at colleges and universities around the country. Most of the discoveries, however, I made for myself, which provided half the fun of this undertaking. I love rummaging through historys back rooms in search of forgotten figures. For years, Ive kept files on intriguing, little-known people Ive come across in my readinginformation that became the basis for this book.

Sometimes, a name alone has been enough to grab my attention. Poking through dusty tomes and faded documents in the Library of Congress and National Archives, I encountered a parade of memorable monikersJimmie Angel, Anne Royall, Andrew Jackson Higgins, Golden Rule Jones. Once, while researching the first American to receive a military decoration, I made an unrelated findan enigmatic colonial patriot named Hercules Mulligan. How could anyone not want to know more about someone with such a fantastic handle?

Delving into the backgrounds of these amazing Americans, I felt like Id dropped in on an underground bash where every guest had a riveting yarn to spinwith each of their stories affording a new perspective on our countrys heritage. So let me welcome you to the party. Now, if youll come with me, Id like you to meet someone interesting.

PAUL MARTIN

Voyagers

The Intrepid Leopard Wrestler

CARL AKELEY

T he parched air pulsed with the feral melody of Africa at duskthe guttural cough of a lion, the nervous shrieks of a restless troop of baboons, the insane cackles of a pack of hyenas. Gazelles and other small animals scurried through the brushy terrain. The interplay of sounds reflected a density of life found in few other places on Earth. Thirty-two-year-old Carl Akeley had quickly fallen in love with this untamed symphony. He was on the first of his five trips to Africa, an 1896 expedition to Somaliland to gather animal specimens for the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Earlier this day, hed shot a warthog, and now he was trying to locate the carcass to take it back to camp, where it would be prepared for shipment to the museum.

As Akeley searched in the fading light near a sandy riverbed, he spotted a hyena trotting through the tall grass. The hyena had the head of Akeleys trophy in its jaws. That burned me up, he recalled, because it was a fine specimen. Akeley turned toward camp in resignation. Trudging along, he glimpsed an indistinct shape slipping behind a bush. Another hyena, thought Akeley. Although he knew it was foolish, he raised his rifle and fired at the phantom hyena. The sound that answered startled him: a wounded leopard growled in anger.

Akeley knew he was in trouble. Leopards dont scare easily, and though smaller than lions, theyre extremely dangerous when provoked. Deciding that retreat was the best option, Akeley picked up his pace. As he crossed the dry riverbed, he looked back and saw that the leopard was trailing him. Even though it was nearly dark, Akeley fired wildlythe last three bullets in his gun. He was sure hed killed the animal with his final shotuntil the leopards snarls signaled it was about to charge. Terrified, Akeley started running, trying to load another cartridge in his rifle as he stumbled along. Just as he rammed home a cartridge and wheeled to face the leopard, the big cat pounced, knocking the rifle from his hands. The leopard went for Akeleys throat but missed and sank its teeth into his right arm near the shoulder.

Still standing, Akeley grabbed the leopards throat with his left hand and squeezed its windpipe as hard as he could, causing it to loosen its grip. Akeley worked his right arm free and forced his fist deep into the animals mouth to choke off its air. He threw the thrashing leopard to the ground, landing on top of it with his knees on its chest. His first shot had hit the leopards right hind foot. With one foot injured she couldnt get a purchase in the loose sand, he said afterward. Otherwise Id have been disemboweled in ten seconds by her hind claws. Akeleys weight on the leopards chest broke at least two of its ribs, and the animal finally succumbed. Nearly done in from exhaustion and loss of blood, Akeley staggered back to camp, where his friends patched him up. Hed just survived the first of several tests that Africa would throw at him during thirty years of roaming the wilds to collect wildlife specimens, most of that time for New Yorks American Museum of Natural History.

During his adventure-filled decades from the 1890s to the 1920s, Akeley forged a reputation as the worlds most talented creator of natural history dioramas. Experts said his exhibits raised the practice of taxidermy to the level of art. Perhaps thats because Akeley regarded his subjects as works of art themselves, whose beauty he tried to preserve forever. Most people whove seen Akeleys surging, trumpeting elephants in the American Museum of Natural History would agree that he succeeded. The majestic animals seem about to thunder off down the hallways just like they did in Night at the Museum . Although killing animals for display has thankfully been superseded by nature films and zoo exhibits featuring realistic habitats, Akeley made the wonders of far-off landsboth the animals and their settingsaccessible to millions of people who would never get to Africa. He also had a surprising role in protecting Africas wildlife.

Akeley spent his entire life around animals. Born in 1864, he grew up on a farm near Clarendon, New York. He became interested in taxidermy when he was thirteen. His first subject was his teachers dead canary. Miss Glidden was thrilled when he gave her back her birdcage with her little friend inside, perched on a branch with its head cocked as if it were listening. Akeley took lessons in sculpture to help him accurately capture the shapes of animals, and he studied painting so he could depict realistic backgrounds for his mounted birds, something that had never been done before. When he was nineteen, he went to work for Henry Wards Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York (at the lofty salary of $3.50 a week). The top taxidermy shop in the country, Wards supplied mounted specimens to museums and universities and also trained museum curators. Akeleys first important assignment there was to help mount P. T. Barnums beloved circus elephant, Jumbo, a huge African specimen that had thrilled audiences in England and America for years until it died in a train accident.