O THER B OOKS BY E DMUND S. M ORGAN

The Puritan Family: Religion and Domestic Relations in Seventeenth-Century New England

The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (with Helen M. Morgan)

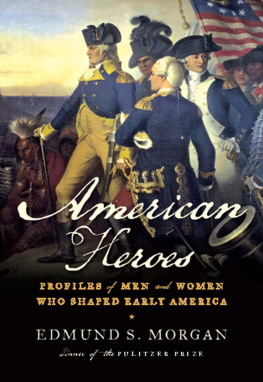

AMERICAN HEROES

PROFILES OF MEN AND WOMEN WHO SHAPED EARLY AMERICA

Edmund S. Morgan

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

These essays are reprinted with the kind permission of the following: Dangerous Books, The Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review ; The Unyielding Indian, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library of Brown University; John Winthrops Vision, Huntington Library Press; The Puritans and Sex, The New England Quarterly ; The Problems of a Puritan Heiress, Colonial Society of Massachusetts; The Case against Anne Hutchinson, The New England Quarterly ; The Puritans Puritan: Michael Wigglesworth, Colonial Society of Massachusetts; The Contentious Quaker: William Penn, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society ; Ezra Stiles and Timothy Dwight, Massachusetts Historical Society; The End of Franklins Pragmatism, Yale University Press; The Founding Fathers Problem: Representation, The Yale Review ; The Genius of Perry Miller, courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Copyright 2009 by Edmund S. Morgan

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morgan, Edmund S. (Edmund Sears), 1916

American heroes: profiles of men and women who shaped early America / Edmund S. Morgan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07426-0

1. United StatesHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775Biography.

2. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Biography.

3. United StatesHistory17831815Biography. 4. HeroesUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

E187.5.M67 2009

973.2dc22

2009000714

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

T O THE MEMORY OF

B ARBARA E PSTEIN

CONTENTS

Chapter One

T HE C ONQUERORS

Chapter Two

D ANGEROUS B OOKS

Chapter Three

T HE U NYIELDING I NDIAN

Chapter Four

J OHN W INTHROPS V ISION

Chapter Five

T HE P URITANS AND S EX

Chapter Six

T HE P ROBLEMS OF A P URITAN H EIRESS

Chapter Seven

T HE C ASE AGAINST A NNE H UTCHINSON

Chapter Eight

T HE P URITANS P URITAN : M ICHAEL W IGGLESWORTH

Chapter Nine

T HE C OURAGE OF G ILES C ORY AND M ARY E ASTY

Chapter Ten

P OSTSCRIPT: P HILADELPHIA 1787

Chapter Eleven

T HE C ONTENTIOUS Q UAKER : W ILLIAM P ENN

Chapter Twelve

E ZRA S TILES AND T IMOTHY D WIGHT

Chapter Thirteen

T HE P OWER OF N EGATIVE T HINKING : B ENJAMIN F RANKLIN AND G EORGE W ASHINGTON

Chapter Fourteen

T HE E ND OF F RANKLINS P RAGMATISM

Chapter Fifteen

T HE F OUNDING F ATHERS P ROBLEM : R EPRESENTATION

Chapter Sixteen

T HE R OLE OF THE A NTIFEDERALISTS

Epilogue

T HE G ENIUS OF P ERRY M ILLER

PREFACE

A MERICAN HEROES. Probably most of the people in this book would have disclaimed or disdained the title. Through most of the eighteenth century, while Americans remained colonists of Great Britain, the word carried its ancient meaning of great warrior, with connotations of membership among the gods or demigods who first bore the title in ancient Greece. Among the Puritans of New England it might have been thought sacrilegious to apply the word to any human being, least of all to some godlike warrior. As late as 1748 Benjamin Franklin, writing as Poor Richard, turned the tables on the words implication of veneration for warriors. There are three great destroyers of mankind, he wrote in his almanac, Plague, Famine, and Hero . Plague and Famine destroy your persons only, and leave your goods to your Heirs; but Hero, when he comes, takes life and goods together; his business and glory it is, to destroy man and the works of man. Hero , therefore, is the worst of the three.

Franklin may have been engaged in one of his humorous sallies, playing with popular beliefs by upending them. But he was not insulting anyone his readers would have known. There were no great American warriors then. When Americans gained one in George Washington, he did not fit Franklins description. Franklin was nevertheless second to none in admiration of him and had no trouble knowing whom the Marquis of Lafayette meant in 1779 when speaking of the godlike American hero. But no American since Washington has gained remotely comparable acclaim, and Washingtons continuing preeminence among our heroes probably owes as much to his presidency as to his generalship. The heroes elevated to a place beside him as founding fathers, including Franklin himself, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Adams, were not warriors. Alexander Hamilton aspired to be one and played a minor role at Yorktown, but gained heroic status, if he has it, as secretary of the treasury.

Even before the Revolution, Americans found their heroes in men who had led contests that stopped short of battle: a John Hampden, who would not pay an unlawful tax in the 1630s, but not an Oliver Cromwell, who led a civil war in the same cause. In the 1760s Americans named many towns after heroes who had supported their cause only in parliamentary debate: Pittsburgh, Conway, Barre, Wilkes-Barre. When they became independent, they looked to their own past for heroes and found a collection of them in the Pilgrim Fathers, remembered for their religious faith and popularly depicted on a solemn walk to church. They celebrated William Penn as a peacemaker. And they began to discover their affinity for nameless heroes among themselves who went their own way against the grain, regardless of custom, convenience, or habits of deference to authority. Many were to be found among the people just then pulling up stakes to strike out over the mountains to Kentucky and Tennessee and Ohio. They were the Americans who sassed their betters and got into trouble, the people for whom the Bill of Rights was written, people not generally recognized as heroes but heroes nevertheless. There was Samuel Maverick, appropriately named, who settled himself in happy solitude on Massachusetts Bay six years before the Puritans got there. When they arrived, he fled from their prayers to an island of his own. There were the two Boston carters, my personal favorites, who stood down the royal governor of Massachusetts on a wintry day in 1705. They were carrying a heavy load of wood on a narrow road, drifted with snow, when they encountered the governor coming from the opposite direction. Since they did not turn off the road to let the governors coach pass, he leapt out and bade them give way. One of them then, according to the governors own testimony, answered boldly, without any other words, I am as good flesh and blood as you; I will not give way, you may goe out of the way. When the governor then drew his sword and advanced to teach the man a lesson, the carter layd hold on the governor and broke the sword in his hand, a supreme gesture of contempt for authority and its might.