Claridges Hotel, Mayfair, 1934

DIARY OF DAVID WALLACE, AGED NINETEEN:

BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD, FRIDAY 11 MAY 1934

Had letter from Sheila, saying had seen my mother, who wanted to meet me. All v. queer. Not seen for 15 years. In some ways indifferent. Yet in others I long to see her. I certainly look forward to it immensely. I objectify it all, picture to myself. Young Oxford graduate, meeting mother after 15 years, moving scene, and not me.

BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD, THURSDAY 17 MAY 1934

Letter from my mother; I knew it at once; suggesting meet Claridges next week; had to write to Sheila to find out her name.

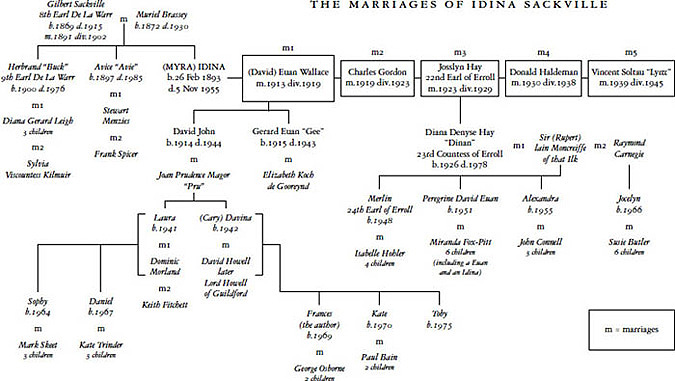

O n Friday, 25 May 1934, the forty-one-year-old Idina Sackville stepped into Claridges Hotel in Mayfair shortly before a quarter to one. Her heels clipped across the hallway and she slipped into a chair in the central foyer. The tall, mirrored walls sent her back the reflection of a woman impeccably blond and dressed in the dernier cri from Paris, but alone. She turned to face the entrance and opened her cigarette case. In front of her, pairs of hats bobbed past with the hiss of a whispershe remained, it was clear, instantly recognizable.

Idina tapped a cigarette on the nearest little table, slid it into her holder and looked straight ahead through the curling smoke. She was waiting for the red carnation that would tell her which man was her son.

IT HAD BEEN TWO WEEKS since she had been told that David needed to see her, and a decade and a half since she had been banned from seeing him and Gee, his younger brother. All that time, she had stayed away. Had it been the right thing to do?

Would she do it the same way again?

That afternoon at Victoria Station when she had said good-bye to a husband she still loved was a lifetime behind her. And the reality of what that life might have been was minutes, maybe seconds, ahead. The cigarette finished, Idina lit another.

And then, as she leant forward, a disheveled young man came through the revolving doors. Six foot two, lean, she could see that he had her high cheekbones and unruly hair. His eyes, like Euans, were a deep brown.

In his buttonhole was a red flower.

For a decade and a half Idina had been searching for something on the other side of the world. Perhaps, all along, here was where it had been.

BOOK ONE

EDWARDIAN LONDON

Chapter 1

T hirty years after her death, Idina entered my life like a bolt of electricity. Spread across the top half of the front page of the Review section of the Sunday Times was a photograph of a woman standing encircled by a pair of elephant tusks, the tips almost touching above her head. She was wearing a drop-waisted silk dress, high-heeled shoes, and a felt hat with a large silk flower perching on its wide, undulating brim. Her head was almost imperceptibly tilted, chin forward, and although the top half of her face was shaded it felt as if she was looking straight at me. I wanted to join her on the hot, dry African dust, still stainingly rich red in this black-and-white photograph.

I was not alone. For she was, the newspaper told me, irresistible. Five foot three, slight, girlish, yet always dressed for the Faubourg Saint-Honor, she dazzled men and women alike. Not conventionally beautiful, on account of a shotaway chin, she could nonetheless whistle a chap off a branch. After sunset, she usually did.

The Sunday Times was running the serialization of a book, White Mischief, about the murder of a British aristocrat, the Earl of Erroll, in Kenya during the Second World War. He was only thirty-nine when he was killed. He had been only twenty-two, with seemingly his whole life ahead of him, when he met this woman. He was a golden boy, the heir to a historic earldom and one of Britains most eligible bachelors. She was a twice-divorced thirty-year-old, who, when writing to his parents, called him the child. One of them proposed in Venice. They married in 1924, after a two-week engagement.

Idina had then taken him to live in Kenya, where their lives dissolved into a round of house parties, drinking, and nocturnal wandering. She had welcomed her guests as she lay in a green onyx bath, then dressed in front of them. She made couples swap partners according to who blew a feather across a sheet at whom, and other games. At the end of the weekend she stood in front of the house to bid them farewell as they bundled into their cars. Clutching a dog and waving, she called out a husky, Good-bye, my darlings, come again soon, as though they had been to no more than a childrens tea party.

Idinas bed, however, was known as the battleground. She was, said James Fox, the author of White Mischief, the high priestess of the miscreant group of settlers infamously known as the Happy Valley crowd. And she married and divorced a total of five times.

IT WAS NOVEMBER 1982 . I was thirteen years old and transfixed. Was this the secret to being irresistible to men, to behave as this woman did, while walking barefoot at every available opportunity as well as being intelligent, well-read, enlivening company? My younger sisters infinitely curly hair brushed my ear. She wanted to read the article too. Prudishly, I resisted. Kate persisted, and within a minute we were at the dining room table, the offending article in Kates hand. My father looked at my mother, a grin spreading across his face, a twinkle in his eye.

You have to tell them, he said.

My mother flushed.

You really do, he nudged her on.

Mum swallowed, and then spoke. As the words tumbled out of her mouth, the certainties of my childhood vanished into the adult world of family falsehoods and omissions. Five minutes earlier I had been reading a newspaper, awestruck at a strangers exploits. Now I could already feel my great-grandmothers long, manicured fingernails resting on my forearm as I wondered which of her impulses might surface in me.

Why did you keep her a secret? I asked.

Becausemy mother pausedI didnt want you to think her a role model. Her life sounds glamorous but it was not. You cant just run off and

And?

And, if she is still talked about, people will think you might. You dont want to be known as the Bolters granddaughter.

MY MOTHER WAS RIGHT to be cautious: Idina and her blackened reputation glistened before me. In an age of wicked women she had pushed the boundaries of behavior to extremes. Rather than simply mirror the exploits of her generation, Idina had magnified them. While her fellow Edwardian debutantes in their crisp white dresses merely contemplated daring acts, Idina went everywhere with a jet-black Pekinese called Satan. In that heady prewar era rebounding with dashing young millionairesscions of industrial dynastiesIdina had married just about the youngest, handsomest, richest one. Brownie, she called him, calling herself Little One to him: Little One extracted a large pearl ringby everything as only she knows how, she wrote in his diary.